This is one of a series of columns by specialists at the Royal B.C. Museum that explore the human and natural worlds of the province.

B.C.’s courts and judicial system date back to the early 1850s (i.e. the colonial period), as do the court records held at the B.C. Archives. Our holdings are sizeable — the single largest and the most comprehensive collection of B.C. court records anywhere, with the most recent being less than 20 years old.

Based on the British legal system, but adapted to local conditions, our court system has developed over the more than 160 years it has been in existence and has become increasingly complex. Our holdings reflect that evolution and complexity.

The courts for which we have records include the Colony of Vancouver Island’s Inferior Court of Civil Justice and Supreme Court of Civil Justice, the Supreme Court of B.C., the Full Court and the Court of Appeal, Assize courts, county courts, mining courts, magistrate’s courts, juvenile courts and family courts.

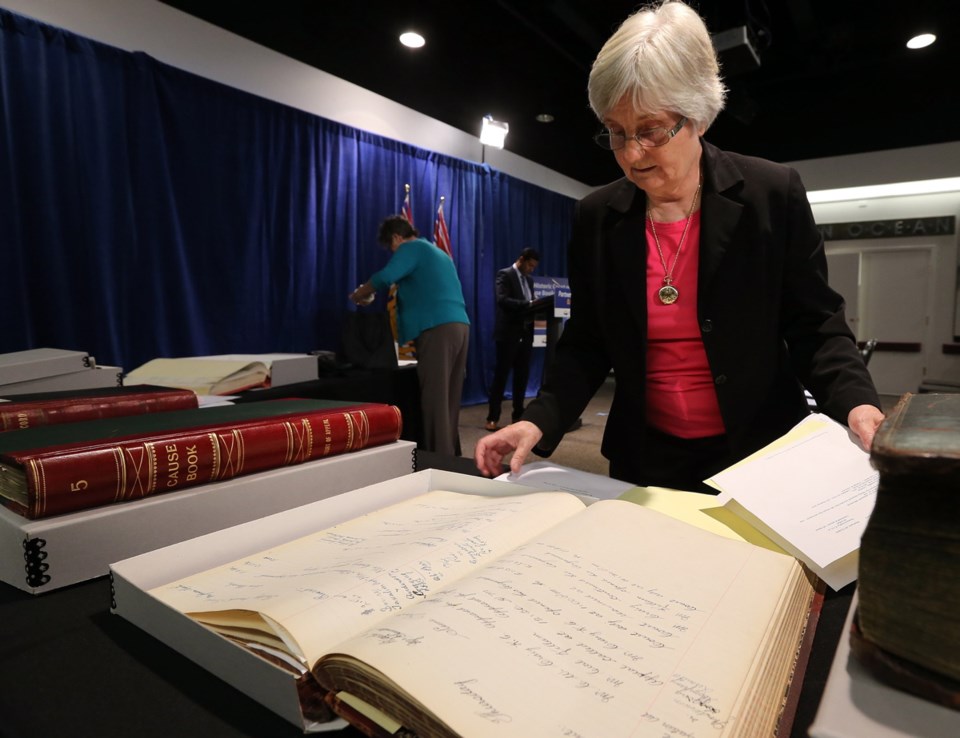

The records include the proceedings and decisions of the courts in civil and criminal actions, documents filed with the court, minute books, cause books, plaint and procedure books, bench books, and registers, indexes, and other tools to manage the records.

In addition to their legal and evidentiary value, these records are a rich source of historical information about the administration of justice since colonial times, but also about other aspects of B.C.’s history in as much as the courts deal with a wide range of issues, including social, political, economic, Indigenous, environmental, cultural, business, labour and human rights.

Requests for and about records for specific court actions and cases come from genealogists for family history and biography; historians and scholars researching a topic; individuals for evidentiary purposes; file and search companies; lawyers, usually for litigation purposes; government agencies; and others. Probate files and divorce orders are probably the most commonly requested and sought court records at the B.C. Archives.

An example of the former is the probated will of Emily Carr, which appointed her executors and gave instructions for the disposition of her estate, including her art works and her papers.

An example of the latter is Francis Rattenbury’s divorce. His wife took him to court and divorced him, not in Victoria where they lived, but in Vancouver, probably to avoid publicity at the time. The page from the cause book shows the proceedings and is the tool that is used to locate the order shown here.

As well, many researchers make use of court records that touch upon a particular topic or field of study; for example, the Landscapes of Injustice project, of which the Royal B.C. Museum is a partner institution. Two examples pertinent to Landscapes of Injustice research are Tomey Homma, arguing for his right to vote in the early 1900s, and the trial of four men for the murder of a Japanese-Canadian man during a convenience-store robbery shortly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

Both cases reflect not only the sentiments at the time, but also the legal arguments and how the legal system dealt with the cases. In the first, the judgment of the B.C. Supreme Court sitting as the Full Court was in Homma’s favour, but was subsequently overturned by the Privy Council in England. In the second, the verdict of murder was overturned by the Supreme Court of Canada and a new trial ordered, which returned a verdict of manslaughter.

Litigation involving Indigenous issues and/or parties date back to colonial times. From colonial cases dealing with whether evidence by Indigenous witnesses was admissible, to more recent aboriginal rights and title cases (e.g. R.V. White and Bob), B.C.’s court records are a rich source for both legal and research purposes.

However, this body of records presents many challenges in terms of access and use, not the least of which are its extent and complexity and the case-name search limitations. As the official legal records of a judicial system, court records are created to suit its needs, purposes and requirements.

The language used, often incorporating terms and expressions in Latin, their format and organization (by individual court registries) as well as how they are managed, recorded and searched (i.e. by case name) do not lend themselves to ease of research access.

For example, an ordinary person looking for a divorce order or a probate file is not interested in how, where and by what court the records were created and managed. For the archivist who must make sense of them and provide the descriptive tools to assist researchers and others in locating specific records, or records by subject or type, it is necessary to be familiar with the history and structure of the courts and the system that created them, as well as their jurisdictional basis and extent.

In the archival world, this is called an administrative history and is a critical component in making sense of the records and developing appropriate search tools, as well as determining legislative and other access restrictions. As more and more court records are transferred to the B.C. Archives and as requests for and research into court records increase, it is needed more than ever. It also helps in locating requested records that are not at the B.C. Archives.

The history of the courts and the administration of justice in B.C. is also a fascinating history in its own right, starting with the unauthorized creation of B.C.’s first Supreme Court by James Douglas and his appointment of his brother-in-law — who had no legal training — as first chief justice.

One of the cases over which he presided was the case of Charles Mitchell, a young African-American who fled his owner in Washington Territory and claimed his freedom once he reached British soil, the Colony of Vancouver Island. When the captain of the ship where he stowed away insisted that he be returned, Chief Justice Cameron ruled in Mitchell’s favour.

Not a bad beginning.

An archivist at the B.C. Archives since 2002, Frederike Verspoor has a particular interest in B.C., Canadian and British government documents and records, including court records (current and historical), statutes and case law. She has written guides to B.C. political history, an electoral history, reference guides on a variety of topics (First Nations research, divorce records, vital-event records, genealogy, colonial government records, etc.) and historical articles.