I enjoy a good snowfall like the one we had last week. My friend Sarah and I bundled up and trudged to Beacon Hill, meeting under the flag amongst a sea of joyous noisy sledders in pink and yellow snowsuits, tuques and mittens careening down the slope on crazy carpets, flying saucers and flattened cardboard boxes.

After we crashed a few times, we ventured to a bench overlooking the leaden sea in a white world. The only colour was the orange beaks of the foraging oystercatchers on the cold black rocks below, and a snow-covered sprig of tough yellow gorse clinging to the cliff.

Sarah had brought mugs of cocoa (she’d added another ingredient) and we sat there extolling the glories of winter. There soon arrived two jovial and excited men, who told us in broken English that they were Syrian immigrants and had never seen snow. They built the funniest snowman I have ever seen — very squat, with a little head and rosehip eyes.

The largest snowman in Canada sits in Beardmore, Ont., 200 kilometres north of Thunder Bay. Canada seems to love constructing big, locally relevant items, especially in New Brunswick, where you might come across the biggest lobster (Shediac), the biggest axe (Nackawic) or the biggest fiddlehead (Plaster Rock). Here on the Island, Duncan has the honour of having the biggest hockey stick.

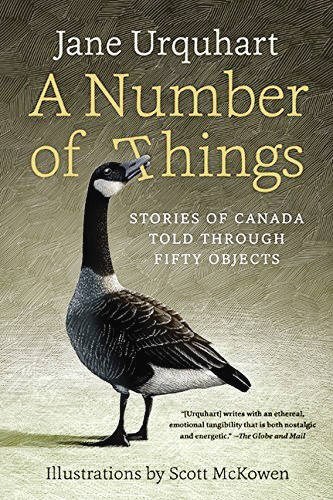

You can read about the immense snowman in Beardmore in a lovely little book called A Number of Things: Stories Of Canada Told Through Fifty Objects by Canadian author Jane Urquhart (2016, HarperCollins Publishers Ltd.). The book, which is exquisitely illustrated with engravings by Scott McKowen, is a collection of reflective, often poignant essays, each describing a symbolic (frequently multicultural) Canadian object that resonated with the author.

You can read about the immense snowman in Beardmore in a lovely little book called A Number of Things: Stories Of Canada Told Through Fifty Objects by Canadian author Jane Urquhart (2016, HarperCollins Publishers Ltd.). The book, which is exquisitely illustrated with engravings by Scott McKowen, is a collection of reflective, often poignant essays, each describing a symbolic (frequently multicultural) Canadian object that resonated with the author.

Although it’s ever so slightly melancholy and sombre in places, it is a very informative, gentle read in a pensive and meditative way. In my view, the history and diversity of Canada does indeed have an often wistful tone to it — the whole idea of establishing a home, or interrupting a home, in such an empty, spacious land.

My suggestion is to read one chapter and ruminate on it (ruminate — the word reminds me of serenity, of contented goats watching the world float by).

Innu Tea Doll addresses how teas and grasses grown on the tundra were gathered and stitched inside these unique dolls and transported by the Innu as they travelled across their hunting grounds. The dolls were originally made of caribou skin, but later from coloured pieces of fabric brought by the Europeans.

The essay titled Ferry discusses the crucial little vessels that are found throughout our enormous land of rivers and waterways. When my father died a gentle and contented death in the Saint John, N.B. hospital, Mum and I took the scenic route back to Fredericton. It was a glorious bright autumn afternoon with a huge gleaming blue sky. The maple forests were a blend of golden ochre and crimson, and the apple orchards teamed with bushels of Macs for sale under rustic roadside shanties that lined the country lanes in the crisp air.

We took two little ferries across the Kennebecasis and Saint John Rivers. A local farmer was transporting his cows across the former, and one poor old dear lost her balance on the ramp and fell into the cold brackish water. Everyone pitched in to pull her out successfully — the ferry crew used the life-ring ropes and the captain put a blanket on her shivering boney back. The two little ferry crossings served as a connection between Dad’s stuffy hospital room, his death and the necessity to carry on — we had to get home to feed Ernie, Dad’s old cat.

As it is Black History Month, I should also mention the essay on the Africville Church in Halifax. Halifax has a vast Black community and in 1849, a church was built in the Bedford Basin area. A vibrant, although poor, Black community grew up around it, creating a close-knit community called Africville.

In the mid-1960s, the community was deemed a slum, however, and the city decided to take action — parts of this traditional neighbourhood were demolished, including the church, thereby shattering the community’s hub, sense of identity, its strong established way of life and its home.

This little book is an enchanting read with quite an introspective tone — the author’s reflections become our own, which is important as we trudge through this odd masked COVID winter within our own community bubbles.