Do you recall your early history lessons in school? I loved history, but my desire to learn it almost fizzled in high school when I enthusiastically wrote an essay on the use of perfume in the 18th-century French court.

I distinctly remember being fascinated that due to the lack of plumbing, and therefore bathing, the palace courtiers, as well as the king, doused themselves in perfumes to conceal their bodily stench. I proudly handed in my essay to the teacher, a little pale man with a face like dried parchment who was always scratching behind his ears, causing tiny flakes of skin to gently fall onto his shoulders.

He returned my essay, on which he had scrawled in great orange crayon: “You’ve got to be kidding!” My mark was zero — Fredericton High School, 1977. Well, what was to be done?

I think I just ate five Tim Hortons doughnuts at the strip mall down the street and sauntered slowly home.

These days, students are bused to museums and art galleries, and to forest streams to see the salmon run, or they’re introduced to First Nation carvers or storytellers. We certainly know now that hands-on history is the way to engage and learn.

History will come alive for you, too, if you visit two local historic sites described in a couple of excellent books.

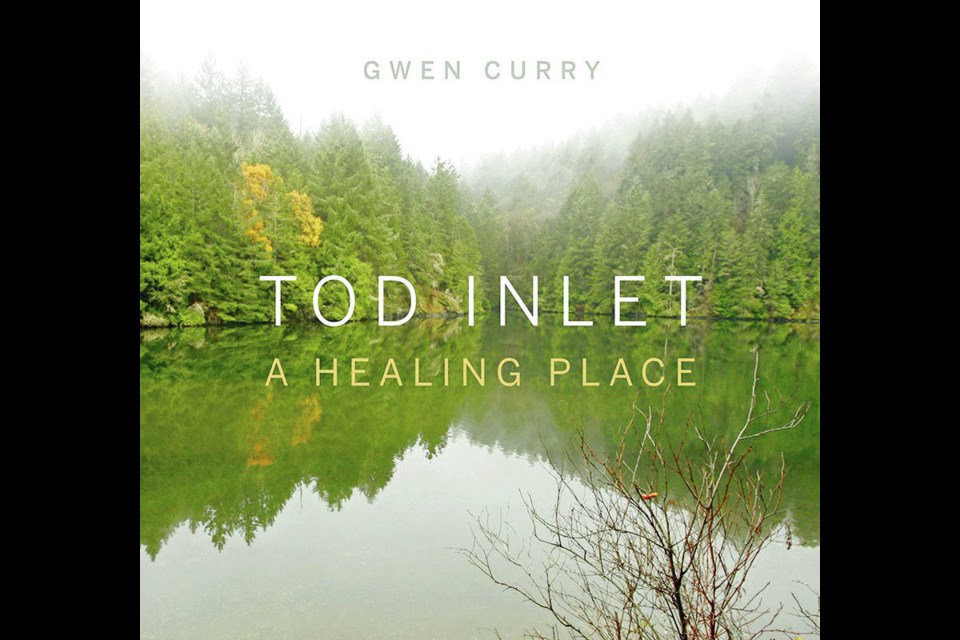

If ever a book was written from the perspective of love and beauty, it is Tod Inlet, A Healing Place by Gwen Curry (Rocky Mountain Books, 2015). Every sentence, every photograph, every observation, every reflective moment of awe or calm and every bit of research exposes the author’s sensitivity and adoration of this very special historic and spiritual site, recorded not with sentimentality, but with an enormous empathy toward the natural world and how it has shaped us through time.

It is this combination of natural and historical activity that makes this book, which is divided into seasonal chapters, so enchanting.

As she wanders down the wooded path to the sea, she observes the crumbling remains of the lichen-covered men’s bunkhouses, wedged amongst the spindly alders, cold, dark, grey hovels built for the workers of the Vancouver Portland Cement Company in the early 20th century.

She also describes the delicate slimy green-capped parrot mushroom pushing up from the decaying leaves on the forest floor, as well as the glazed crockery shards and salt-encrusted glass remnants left by the Chinese workers (200 men at the peak of cement production).

She mentions the First Nation antidote for shellfish poisoning (salal berries), and touches on wild sweet peas, electric boats, abandoned limestone quarries (Butchart Gardens is right next door), boggy skunk cabbages, purple martin nesting boxes, a banana slug sliming across bits of moss-covered rusted-out machinery — the site is, as the author observes, a wonderful blend of human industry and the forest ecosystem.

The Tod Inlet path is off Wallace Drive, and parking is along the road (dogs must be on a leash).

If you enjoy detailed and meticulous writing and research, you will be engrossed by The Gorge of Summers Gone, A History of Victoria’s Inland Waterway by Dennis Minaker (1998). There’s an abundance of black and white photographs, diary entries, charts, menus and newspaper reproductions, facts and dates and data.

The book is a description of life on the Gorge following the removal of the First Nation villages. After the development of Fort Victoria, the First Nations people “all moved to reserves on Esquimalt and Victoria Harbours.”

We now know the sad and bullied history of how we treated the Indigenous community, and I feel hopeful that we can make amends, perhaps by reading, understanding and thinking about our past actions, particularly a history that focuses on this special place, the Gorge.

This book describes numerous waterfront activities, such as high-diving competitions, including one that went horribly wrong for diver Billy Muir, whose spinal cord was crushed.

Eventually, the Gorge was polluted by sewage and effluent from slaughterhouses. “Human excrement floating past young bathers was not unusual,” writes Minaker. Swimming was banned in 1939 due to a typhoid-fever outbreak.

These days, though, my friends Emily and Sofia and their pals swim in the Gorge during our hot summer days and live to tell the tale!