Even without the murder, it would have been hard to live under the weight of his famous but scandal-tinged father’s name.

Even without the murder, it would have been hard to live under the weight of his famous but scandal-tinged father’s name.

Yet John Rattenbury, orphaned by homicide and suicide as a child, grew up to become a noted architect, too, having been mentored by Frank Lloyd Wright — his surrogate parent.

And, despite his boyhood trauma, Rattenbury also proved to be a wonderful father, says his stepdaughter Celeste Davison. “I called him Dad. He earned Dad.”

It all makes for a long, twisting Father’s Day story that began when Rattenbury, who died in Arizona in March at age 92, was born in Victoria two days after Christmas 1928.

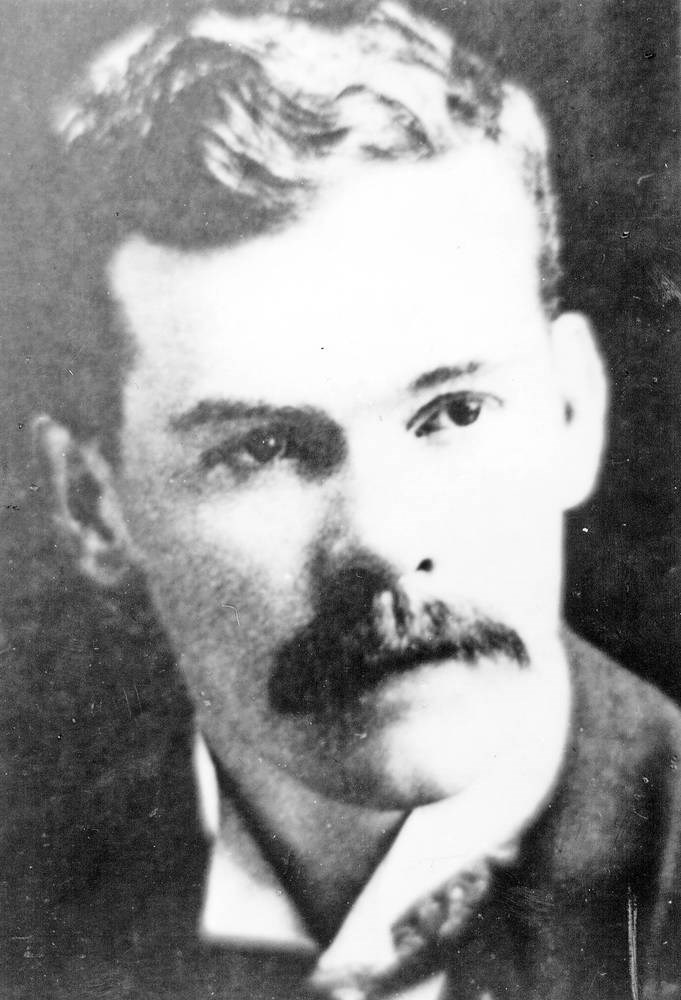

By then, his father Francis Rattenbury’s fingerprints were all over the capital. Francis had been just 25 years old, fresh out from Yorkshire, when he won the competition to design B.C.’s parliament buildings in 1893. Then came Victoria’s other landmark structure, the Empress Hotel, and work on the likes of the Crystal Garden and CPR steamship terminal.

But Francis’s star was already fading and his long marriage loveless when in 1923, at age 56, he met Alma Pakenham, a vivacious concert musician and songwriter less than half his age. Kamloops-born Alma had already been married twice (her first husband was killed in the First World War and she divorced the second) by the time she took up with Francis, whose behaviour shocked Victorians.

“He flaunted her publicly and even took her back to his home, where his wife, Florence, would be taunted by the sound of their lovemaking,” is the way the Scotsman newspaper put it this year.

Francis and Alma eventually married, living in a Rattenbury-designed home that now houses the library, music room and offices of Glenlyon Norfolk School’s Beach Drive campus. Their son John was still a toddler, though, when, ostracized in Victoria, the family moved to Bournemouth, England.

That’s where the real scandal occurred, the gory, salacious one that would make headlines on both sides of the Atlantic.

In March 1935, as Francis sat dozing with a drink in the Rattenbury home, Villa Madeira, someone clobbered him in the back of the head with a wooden mallet. Alma at first indicated she was responsible, but blame soon shifted to the family’s teenage chauffeur and household helper, George Stoner, with whom she had been having an affair. He was arrested after telling a housekeeper he had done the deed.

Both of them went to trial in what was the 1930s equivalent of the O.J. Simpson case. “The love-triangle tragedy, with its heady ingredients of sex and class, was one of the greatest scandals of the time,” Britain’s Telegraph newspaper recalled in a story this spring. “Queues formed each morning to gain admission to the court, where Alma was vilified by her own counsel as a woman who ‘by her own acts and folly had erected in the young man a Frankenstein of jealousy.’ ”

Alma was portrayed as having led Stoner astray, to the point that he took it upon himself to attack her husband. “One of the details that so shocked spectators in court in 1935,” theTelegraph story said, “was that young John had shared a bedroom with his mother, sleeping across the room in his own single bed while she fornicated with Stoner in hers." She told the court her son was a sound sleeper.

Alma was acquitted while Stoner was convicted and sentenced to hang. Five days later, Alma stabbed herself in the chest half a dozen times before falling into a tributary of the Avon River, dead. Stoner, however, survived: After more than 300,000 people signed a petition asking for clemency, he ended up serving just seven years before being freed to fight in the Second World War. He died in 2000 at age 83.

It’s against this backdrop that John Rattenbury was raised.

“I remember the night my father was murdered because the lights went on in the house and I woke up,” he was quoted as saying in a 2007 story in Britain’s Times. “Nobody would tell me what had happened, but I had this cold feeling that something terrible had occurred.”

In fact, it would be another year before he would learn the truth. “I was too young to know and everybody was afraid to tell me,” he said. “Then one day, a boy at my school rather cruelly told me that my father had been murdered and my mother had killed herself.

“It was such a shock. I’d been told they were on vacation.”

After he attended a series of boarding schools, a guardian had John shipped in 1941 to the wartime safety of Vancouver, home to Alma’s mother – though when she died soon after his arrival, he ended up living with an aunt. It was at Vancouver’s St. George’s School that he won $5 in a student school-design contest. “I wasn’t aware that I was following in my father’s footsteps but I guess it was in my blood,” the Times quoted him as saying. “I’d also seen him at work and that must have sown a seed.”

After school, he worked for a logging company, attended UBC and then moved on to Oregon State College to study architecture. Along the way, he came across some writings about Frank Lloyd Wright and his philosophy of connecting architecture with nature. Inspired, John eventually made his way to the Arizona desert and Taliesin, the home, architecture school and community Wright had founded.

Wright had endured his own share of tragedy. The woman he loved was among seven people murdered by a deranged employee at the site of the original Taliesin, in Wisconsin, in 1914. Maybe that played a role in drawing the two men together. For whatever reason, Wright became both mentor and substitute father to John. The famed architect’s wife, Olgivanna Lloyd Wright, played a big role, too.

“He pretty much worshipped the Wrights,” said Celeste Davison, on the phone from her home in Monterey, California, this month. John married her mother, Kay Davison, who had been Wright’s personal assistant, in 1968.

Davison likened Taliesin to a small, artsy college, one where residents worked together, ate together, and dressed formally for movies and entertainment on Saturday and Sunday nights. Like John, many of the adults there looked at the Wrights as parents — though Davison says the kids who grew up in the tight-knit community weren’t as unquestioning of the leadership. (Note that a dozen years after Wright died, Olgivanna’s domineering ways led Joseph Stalin’s daughter Svetlana to break away from Taliesin. Having fled a powerful, controlling father and Big Brother system in the Soviet Union, Svetlana balked at Olgivanna’s intrusion in residents’ personal lives.)

John thrived at Taliesin, though. He became an important member of Wright’s practice, working on scores of projects, including New York’s breathtaking Guggenheim Museum. After Wright died in 1959, John helped co-found Taliesin Architects, completing Wright projects and becoming known for his own, designs that reflected a belief that people should live in harmony with nature. (In two of his acclaimed Arizona projects, all the cacti and other flora of the fragile desert were collected and replaced after construction.) He wrote books about Wright and architecture, taught and, in 1997, had the winning design of Life magazine’s “dream house.”

He also, despite his own troubled upbringing, turned into a kind, generous, good-humoured family man. “He became the kind of person that, given his childhood, was a big surprise,” Davison says. John exhibited the qualities that were missing from his own young life.

Davison remembers him being serious about architecture, rising at 4:30 and working in his drafting room until 6, but then joining Kay for morning tea. “They were like lovebirds the whole time they were together. It was my mother’s fourth marriage, but this time she hit the jackpot in that they had emotional security with one another.”

He was also good for Davison, who found him a terrific father.

How did he come to terms with his past? By looking at the positive.

“He just sort of dismissed his own bad childhood,” Davison says. He adored his mother, extolled her musical prowess, fondly recalled memories of her playing with John and Christopher, her son from her second marriage. “He had that good memory, thank goodness,” Davison says.

John rejected the idea that his mother had anything to do with the murder. “I don’t believe that for a moment,” he told the Times in 2007. “My mother was too naive and innocent to do anything like that.”

He acknowledged she was troubled, though, a vibrant, beautiful woman who was not only getting into drink but perhaps drugs as her reclusive and unhappy husband aged and drank. He was sympathetic when talking of the dark place they found themselves in.

Still, that wasn’t John’s focus: “Very few people mentioned my parents’ good qualities — my father’s architecture and my mother’s musicianship,” the Times quoted him as saying. “That’s how I prefer to remember them.”

Davison confirms that. “He was very happy to be part of the Rattenbury family,” she says. “As an adult, he was very proud of his father.”

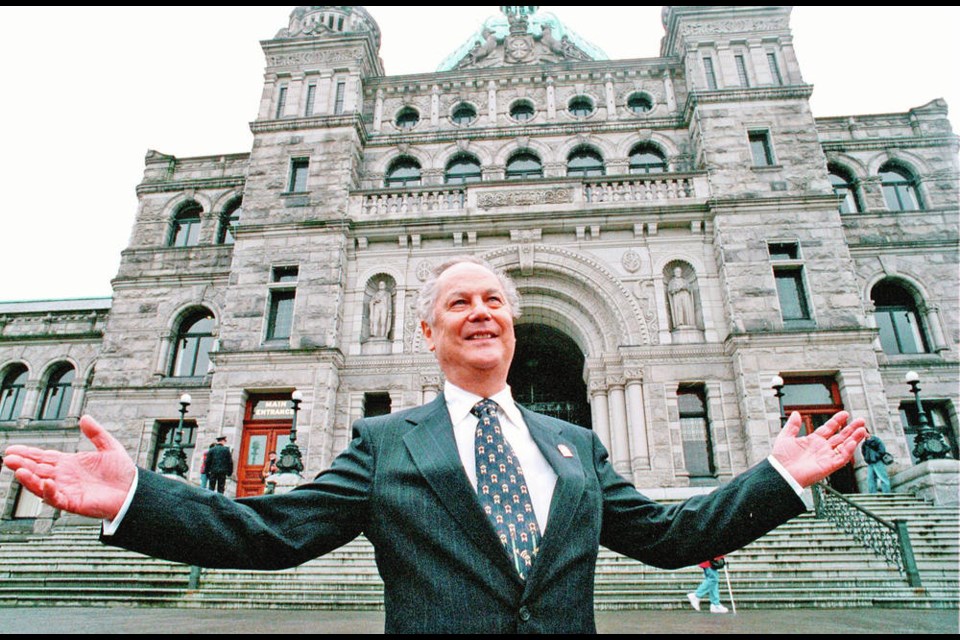

That’s why it was such a high moment when he came to Victoria for the 100th anniversary of the legislature buildings in 1998. A photo taken at the time shows him with arms spread wide in front of the legislature. “I just love that picture,” Davison says. “That was a peak experience for him. He loved the love that his dad received.

Much has been written about Francis and Alma Rattenbury. English playwright Terence Rattigan’s Cause Célèbre was based on their story (the television version starred Helen Mirren). Pacific Opera Victoria premiered Tobin Stokes’s Rattenbury in 2017. There are several books, including 1978’s Rattenbury by Victoria’s Terry Reksten and Sean O’Connor’s The Fatal Passion of Alma Rattenbury, which made the Times’ list of best books of 2019.

On Father’s Day, though, it’s worth sparing a thought for the little boy the tragic couple left behind, and how their loss affected him and who he became.

“He was,” Davison says, “a fine human being.”

jknox@timescolonist.com