The Inner Harbour is a stage on which our public ceremonies are played out. Public sculpture is a significant part of this, as I noticed on Remembrance Day last weekend.

On the macro scale, the magnificent dream of 25-year-old Francis Ratten-bury will never be gainsaid. His legislature buildings stand against the Olympic Mountains, and the neo-Classical Canadian Pacific Steamship terminal welcomes guests to the grand chateau-esque hostelry named the Empress.

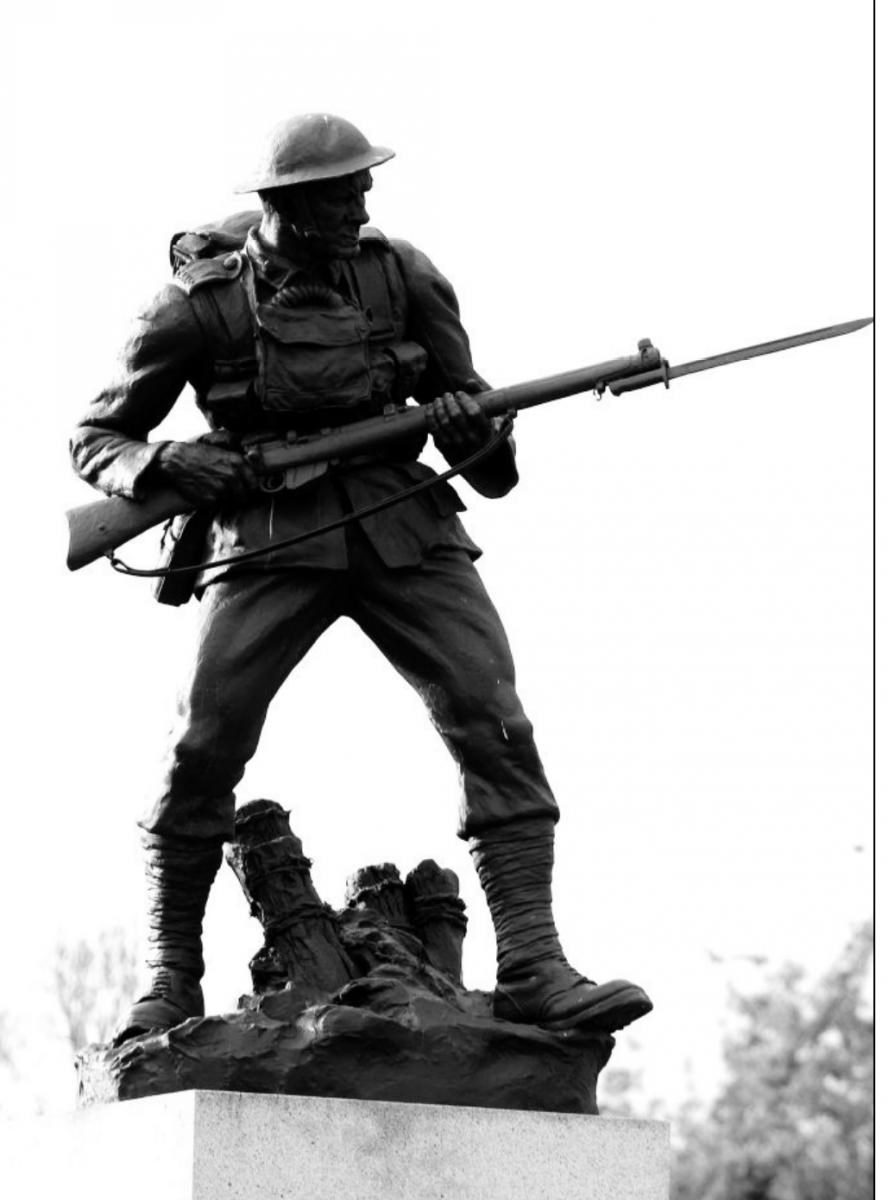

While we gathered by the War Memorial, moved by the music of the superb Naden Band, I cast my eyes up to the dramatic bronze infantryman (1925) by Sydney March, set high above us on a stone plinth. That lone soldier's bayonet stood out sharply against the bare branches of a nearby maple. The National War Memorial in Ottawa is another of March's creations.

Across the lawn presides Aston Bruce Joy's sculpture of Queen Victoria (1921), facing our Inner Harbour. She casts her eyes downward, and seems a bit taller than I remember her, but perhaps Joy knew better.

Overlooking it all is George Vancouver, distantly glinting from the top of the legislature's dome. More effective from street level is the statue of Captain Cook (1976), commanding the stairs to the causeway across from the Empress. The base of the monument is signed "Tweed."

I don't know what Cook actually looked like, but his rolled map, forthright stance and masterful gaze all speak of the confidence of the colonist. It may come as a surprise to find that Cook is fibreglass, not bronze.

Perhaps Cook's dominance has something to do with the two-metre-tall pedestal he stands on. Barbara Paterson's bronze Emily Carr (2010) at Government and Belleville streets is intentionally set at ground level, where, with her dog, she welcomes visitors. Her gaze is turned skyward, making a counter-point to the statues of conquering men. This doesn't look like Carr to me, and she was modelled somewhat larger than life. Her head and hands seem too big and the artist's grasp of scale is less than assured.

Nathan Scott's two-part sculpture at Ship Point honours the navy. The exactly life-size Veteran Sailor sitting on the park bench makes a play upon reality that is surprisingly effective. Nearby, The Homecoming scene, a returning sailor whose daughter is running into his arms, is sentimentally sweet, but highly successful as public art. At any time you'll find people observing, reflecting and interacting.

There's more to public art than realism. On the corner of the harbour is a Kwakiutl totem pole by Henry Hunt, featuring a bear holding a copper shield (1966). The First Nations presence on this spot, once a famous clam bed, has evolved from simple tourism. On the lawn of the legislature is the towering Knowledge Totem (1990) by Cowichan carver Cicero August and his sons. Such tall carvings were not in the Salish tradition but this location seemed to demand something majestic - and unique.

From the War Memorial I looked east to see the grove of 11 totems - mostly Haida - outlined against the autumn leaves of Thunderbird Park. Anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss was right to describe the art of the Pacific Northwest as one of the great plastic art traditions of mankind.

Down on the causeway is one of a number of oversize bronze spindles and whorls, the work of Butch Dick. They have been placed to draw attention to locations around Victoria that were significant to the Esquimalt and Songhees people.

Recently, excellent informative plaques have been installed to help us understand what this enchanting waterfront was like before the Europeans arrived.

To read the concise and informative Signs of Lek-wungen is to peel back the surface of our received history and reveal the heart beneath.

While some may question the insertion of a modern sculpture into the historic precinct of Bastion Square, I enjoy Illarion Gallant's skeletal Commerce Canoe, held up by swaying reeds. The beautifully crafted aluminum boat holds three seed pods, suggesting many things in their understated way.

In the end, it is the public that dignifies public art with its attention. Day is For Resting, Night is For Sleeping (1997) was created by Mowry and Colin Baden and stands, ignored, near the corner of Beacon Hill Park.

Perhaps the artists began by wondering what one could do with a mattress in the daytime - make a sofa or a bench of it? Then they built the bench and sofa with an implicit joke - what looks soft and pink is in fact it cold, hard concrete. Finally, to state the obvious, they erected an overwhelming signpost.

The mattresses, grown mouldy, look forlorn. The signage is out of scale. Most people driving by miss the point. But this artwork does have its effect. Every time I see a real mattress on a boulevard, awaiting disposal, I think of it.

robertamos@telus.net