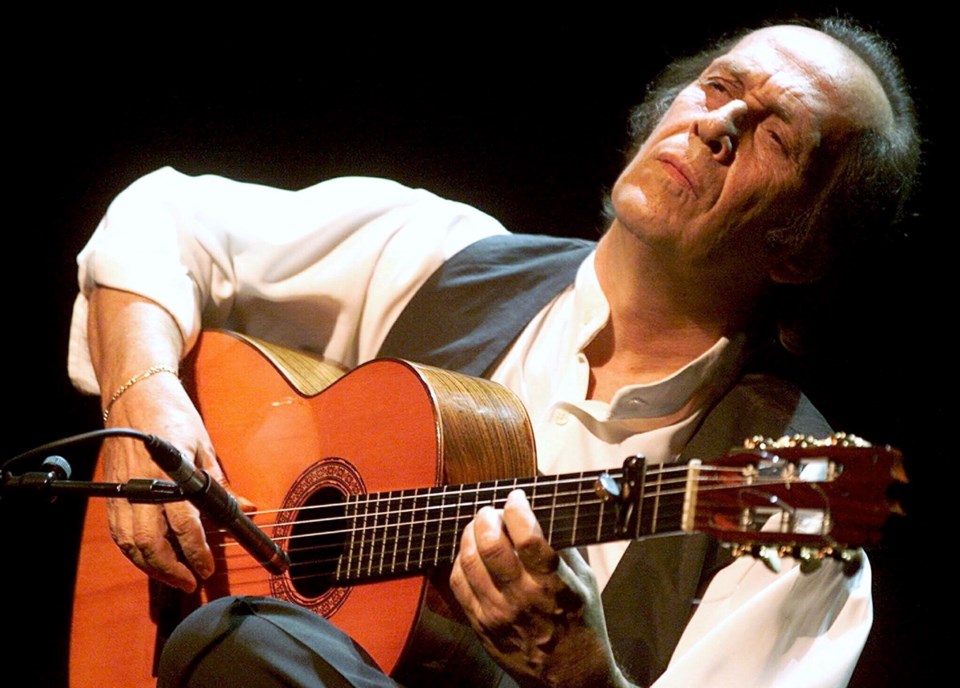

Times Colonist arts writer Amy Smart interviewed Paco de Lucía in Spanish in 2011. The world-renowned flamenco guitarist died this week in Mexico at age 66.

Listen closely and Paco de Lucía's guitar might speak to you.

“It’s the most universal language,” said the flamenco guitarist in a Spanish-language interview. “Music is a direct language — a language that moves directly from heart to heart. With words there is always speculation, with music there is not.”

Though he speaks poetically, de Lucía says he communicates best with his audiences around the world by song.

“It’s much easier to communicate through playing than with words — even in my own language,” he said by telephone from Mallorca, Spain.

Coming from anyone else, this might seem a little over-the-top.

But from de Lucía, arguably one of the greatest living guitarists, it’s the honest truth. An interviewer once asked him to perform emotions — play happiness, now play loneliness — and his fingers danced along the strings, communicating the emotions in a way that words never could.

De Lucía will play Saturday at the Royal Theatre, as part of the Victoria International JazzFest.

Though he had a humble start — learning from his father without sheet music — today de Lucía is a world-renowned performer.

Last year, the 63-year-old was awarded an honorary doctorate from Berklee College of Music in Boston. They called him one of the world's greatest guitarists and “the most innovative and influential flamenco artist of his generation.” His music has been revolutionary, they said.

Past recipients include Duke Ellington, Aretha Franklin and David Bowie.

“Revolutionary” is a bold word to describe any kind of music, but in this case, it may be true.

When de Lucía began playing, flamenco was still largely restricted to poorer Gypsy communities in Spain.

Gradually, as stars such as singer Camarón de la Isla rose to fame - someone de Lucía regularly collaborated with before his death - the music spread around the globe. While he didn't name himself among those musicians, de Lucía called them "people who have fought to communicate our language." Flamenco now has a community in every city of the world, he said.

He likened it to blues, in the way that it's a working-class, regionally based art form. In the same way that blues grew out of New Orleans, flamenco grew out of lower Andalusia in Spain.

“For a long time, to the higher classes flamenco was for people with a category — those who were not seen well. Poor people, people without education.”

He said the attitude still remains, among some people. “There are many people in my country who still don’t give it value, because they don’t understand it.”

With more than 30 albums, de Lucía has played a central role in bringing the improvisational and community-driven music beyond its initial barriers.

With many accolades and acclamations under his belt, you'd think he might take a break from touring or production. But there's no end in sight for him.

Sometimes, he says, he gets a bit tired of playing. “But on the other hand, what can I do if I don’t play? Playing has been my passion for my whole life. I can’t stay home and just watch television.

“When I can’t play anymore, I won’t. . But I have some energy yet.”