TORONTO - In the wee hours of almost every morning, Dustin Hoffman rouses from bed, pours some coffee and meticulously scans the pile of more than a half dozen newspapers delivered to his doorstep each day.

Part of what he finds in those crisp papers (in those crisp hours) is inspiration. He loves reading about the tireless achievers still aiming high in their twilight years — you know, stories about the 104-year-old filmmaker or the 94-year-old triathlon runner.

While still a few decades away from such longevity, Hoffman might be also considered an inspiring example: the 75-year-old first-time director, making his behind-the-camera debut with the light-hearted new dramedy "Quartet," opening Friday.

"There is that attitude — you resist the clock, I guess," the buoyantly personable acting legend said in an interview during the recent Toronto International Film Festival, where "Quartet" screened. "You can live your own Einstein Theory, (where) time is relative.

"If there's three acts to a play, I still feel I'm in my second act."

Perhaps not coincidentally, "Quartet" explores similar questions about retaining one's vitality in old age.

Adapted by Ronald Harwood from his play of the same name, "Quartet" focuses on a cluster of former opera singers living together at the Beecham House, a stately home for retired musicians.

Two-time Oscar winner Maggie Smith is cast as Jean, a haughty, difficult diva who agrees to live at Beecham but — saddened and self-conscious over her gradually deteriorating vocal skills — stubbornly refuses to take part in the home's annual gala concert.

Three of her more upbeat new housemates (portrayed by the estimable likes of Tom Courtenay, Pauline Collins and Billy Connolly) work to change her mind — both about singing the quartet from Verdi's "Rigoletto" but also about the process of aging — with their intertwining personal histories never far from the fore.

Rookie directors are rarely blessed with such a gifted ensemble, and Hoffman was quick to point out his good fortune.

"I had to do very little," he said. "Really, all you do is make sure they feel comfortable and alive and give them time to fail. That's the key. In movies, you're not given that.... But you let the actors fail, let them find it. Don't force them to be there right away."

His actors certainly seemed to appreciate it.

Collins, for one, praised Hoffman for his willingness to entertain ideas from anyone on set. Her own performance as a sweet-natured woman beginning to show signs of dementia was informed by watching her own mother struggle with the condition, and she found Hoffman totally receptive to her interpretation.

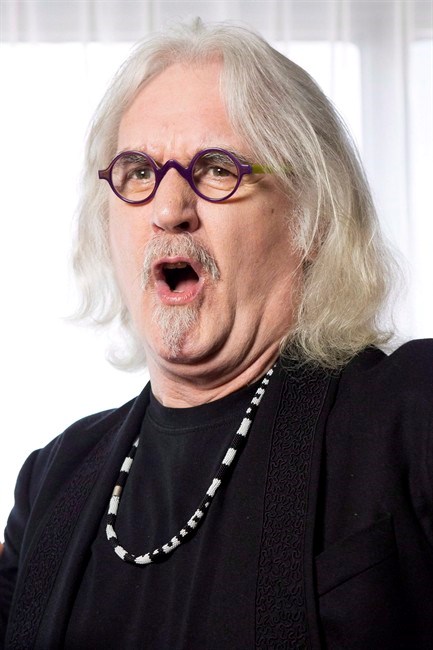

Meanwhile, Connolly — the beloved Scottish comedian with the wild hair, dirty mouth and seemingly ceaseless supply of hilariously meandering anecdotes — admits he was intimidated by the pedigree of his decorated co-stars, so Hoffman's nurturing presence was a relief.

"Oh my God — I was scared to go to work," he said. "(Hoffman) knows, as a world-renowned great actor, what works and what doesn't, and what's too long and what's not long enough.

"It's very, very comfortable to be directed by a guy like that."

Not that all of Hoffman's charges were so reverential.

Courtenay, an Oscar nominee for 1965's "Doctor Zhivago" and 1983's "The Dresser," decided to toy with the director when he saw Hoffman apply a bit of sunscreen to his nose on a sunny day of shooting.

"I said, 'Dustin, when you have that stuff on your nose, it reduces your authority,'" Courtenay recalled, laughing. "It was a complete wind-up. Next time I saw him, (the sunscreen) was gone. I never said anything. I didn't have the heart."

Although an appreciation of its subject matter is hardly a pre-requisite for enjoying Hoffman's sprightly film, the two-time Academy Award winner himself has long been well-versed in opera dating back to his early '20s.

Back then, Hoffman was waiting tables and sharing a cheap apartment in Spanish Harlem with another soon-to-be acting luminary in Robert Duvall, whose brother was an opera singer.

Running in those circles, Hoffman got to know not only the opera, but many opera singers.

"They are a breed," Hoffman marvelled. "I couldn't put it all in the film but they're a horny bunch. I'm not kidding. They get laid between arias!"

But he compares opera singers to athletes in terms of the way their gifts erode or evaporate completely over time.

All the characters in the film struggle with adjusting to age, but none moreso than Connolly's smirking rascal Wilf. But the 70-year-old can't really relate to his onscreen counterpart's age anxiety.

"I think Wilf confuses (aging) with growing up," Connolly said. "Growing old — that's totally acceptable and inevitable. But growing up is a no-no. You mustn't grow up. You become beige and give up all the fun. You start wearing those trousers with the crotch way down at your knees.

"There's no reason on earth to grow up," he adds.

It's a lesson Hoffman has seemingly taken to heart.

On a press day busy enough to turn actors a third his age bleary-eyed, Hoffman is a blur of energy — bursting into co-stars' interviews, telling off-colour jokes, spontaneously answering a reporter's ringing cell phone.

The unusually chatty Hoffman sometimes seems cheerfully determined to steer his interview off course, engaging in asides about Shakespeare, the tobacco lobby or even a reporter's pair of digital recorders that he suddenly covets. ("They look like electric shavers," he says approvingly. "I have to get one.")

"I've never grown up — anyone who knows me dearly will tell you that," he said, to murmurs of agreement from nearby staff members. "I'm an immature person.

"I think what will put me in my third act is — well, something happens to us," he adds later. "When you get sick, you get a cold, and it persists, then it's a week and you've got a horrible flu. Just after a week, you can't remember what it felt like to feel good.

"I think being old — quote-unquote — you lose memory of what it felt like to not be old. And it hasn't hit me yet."