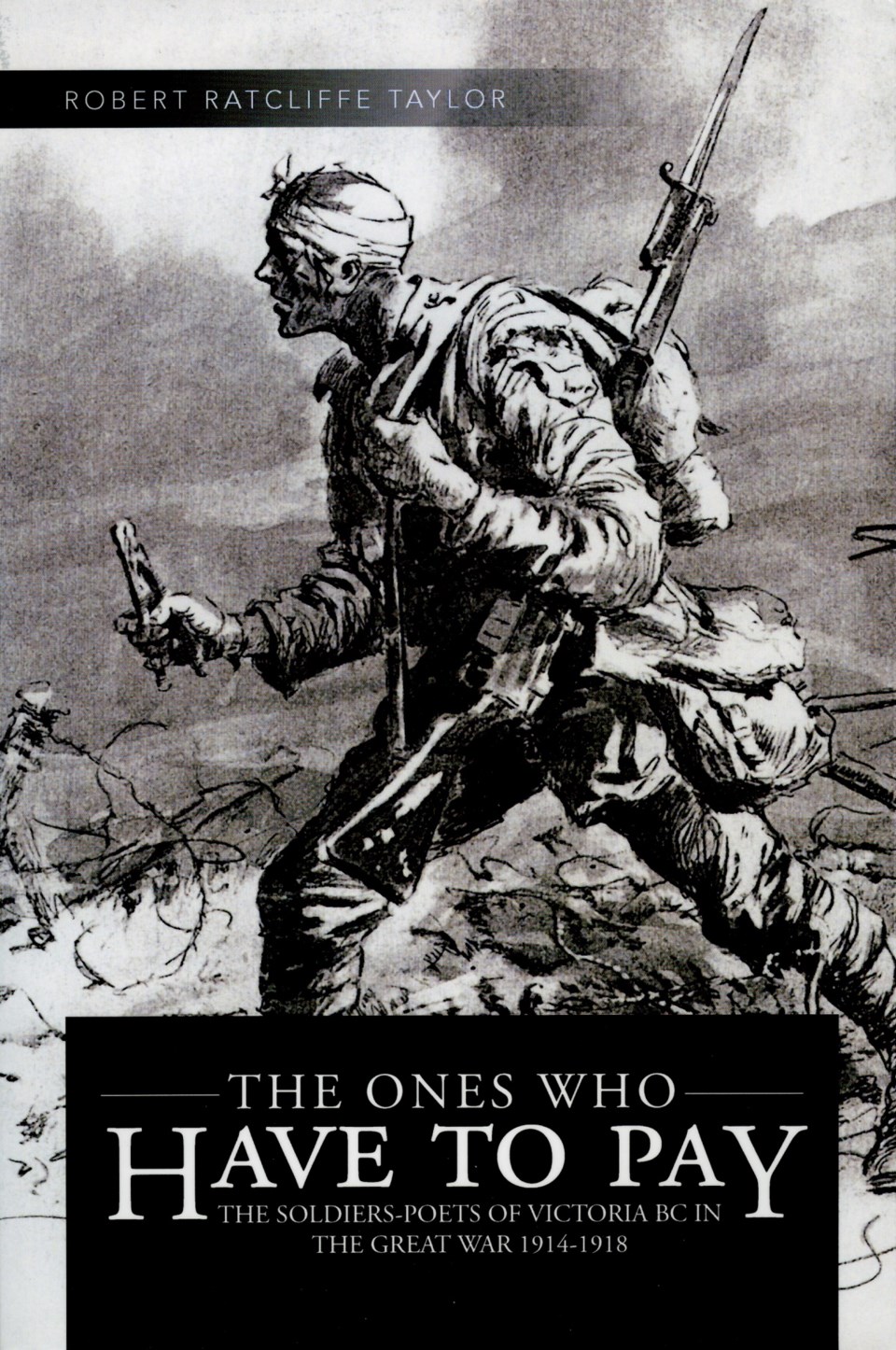

The Ones Who Have to Pay: The Soldiers-Poets of Victoria B.C. In the Great War 1914-1918

by Robert Ratcliffe Taylor

Trafford, 258 pp., $20.50

As we approach the centenary of the start of the First World War, we should expect an onslaught of new material about the war, including many books.

There won’t be many books, however, like this one. Robert Ratcliffe Taylor’s The Ones Who Have to Pay looks at the war from a distinctly local perspective, and through a unique source: The poetry written by soldiers from Greater Victoria.

Many of these poems were originally published in the Victoria Daily Times or the Daily Colonist. The two newspapers also published information on the soldiers involved, and provided a better sense of what the war effort was all about.

In Taylor’s eyes, the war was seen here through a British lens: It was a game, it was the right thing to do, it was a chance for good to triumph over evil through a quick cavalry charge or two.

The poems reprinted here present a generally positive, upbeat attitude toward the war, and the conditions faced in training at the Willows camp as well as on the battle lines abroad. Taylor writes that the poems are a reflection of the pro-British attitude in our community, but he also notes that words about the war were being carefully censored.

It was not until after the war, as the veterans were recovering as best they could, that the truth could be told: It was a horrifying experience for most, as they watched their friends get blown to bits, or drown in the mud of Belgium and France.

We shouldn’t expect, therefore, this book to provide deep insight into what was happening in the trenches. It is instead a look at what the soldiers were willing to write, and what their editors were willing to publish.

The poems make up only a small percentage of the book. Much of it is a narrative by Taylor that provides valuable context for the poetry. His description of the attitudes and conditions here and abroad help us to understand why the poems were written as they were.

In all, it is a remarkable look at our city of almost a century ago, through the words of people who were here at the time. If we could reach back and interview our Great War veterans, they might have used these words.

And that raises another point: The surprising quality of the writing by the soldiers. Clearly, they had been educated in the classics of poetry, because they knew how to mimic the style and use their words to maximum effect.

Taylor, the author and compiler, has written several other books, including a history of the Spencer Mansion, the home of the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria. He deserves high praise for seeing the value in the old poems, and for taking the time to collect them for us.

In the flood of new books on the Great War, this one is well worth reading.

The reviewer, the editor-in-chief of the Times Colonist, is the author of The Library Book: A History of Service to British Columbia.