Frank Sinatra’s prime years as a singer were long behind him when Eliot Weisman managed his career. Yet even into his 70s, “the Voice” could deliver what fans wanted or were willing to settle for. The challenge Weisman soon faced was how to showcase the best of a septuagenarian Sinatra while playing down the ravages of time and handling the unexpected — such as former Israeli prime minister Golda Meir’s Uzi.

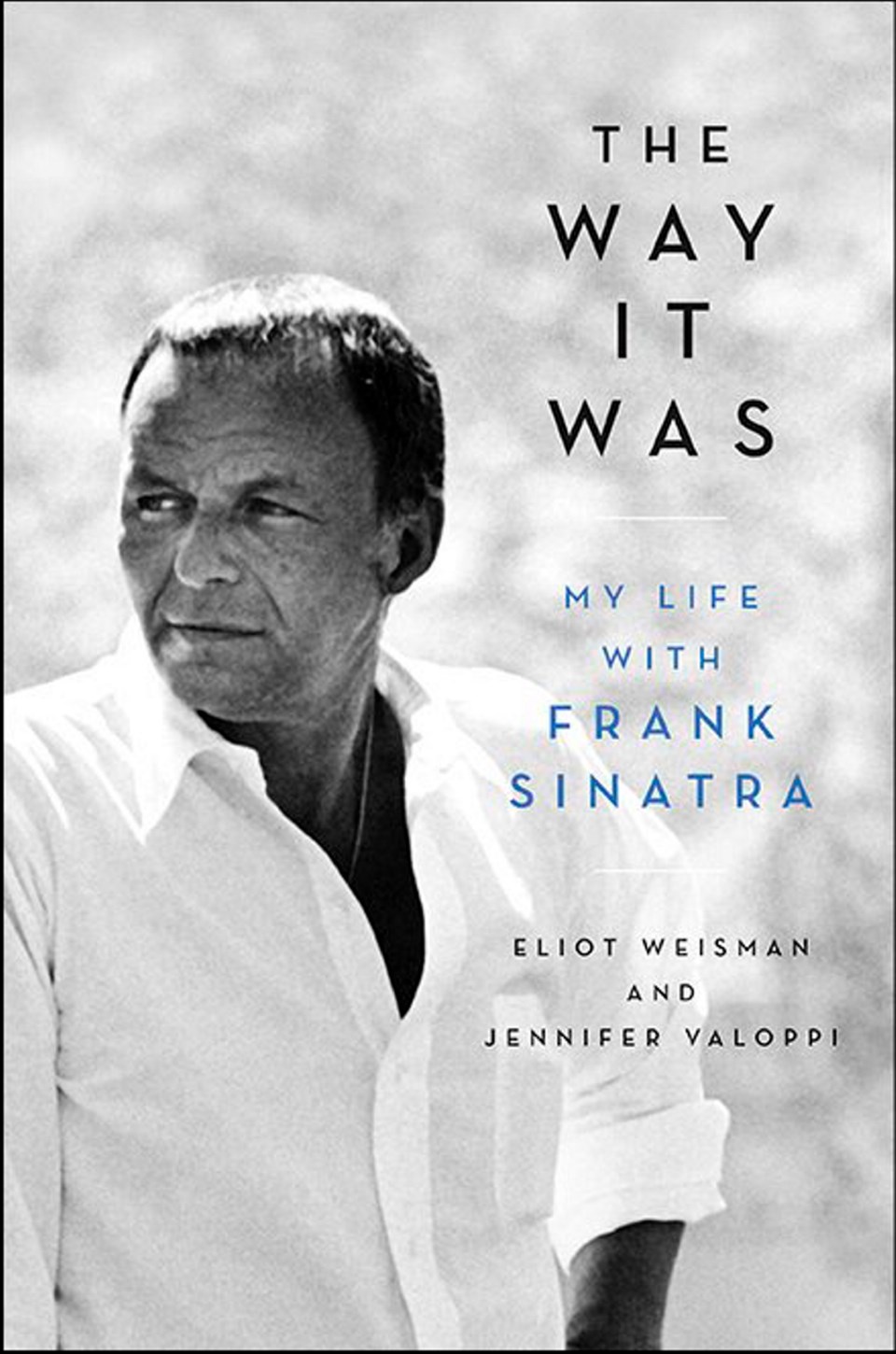

Anecdotes are the diamonds and lessons about problem-solving the gold to be mined in The Way It Was: My Life with Frank Sinatra. Weisman and co-author Jennifer Valoppi recount his 20-year relationship with Sinatra, one based on business and nurtured with trust and friendship. Other celebrities pop up, notably Liza Minnelli and Sammy Davis Jr., but the authors know who sells books even two decades after his death and salt Weisman’s memoir with Sinatra minutiae.

About that Uzi: Weisman became accustomed to the idea that Sinatra often carried a concealed handgun while touring. But he didn’t expect to find a submachine gun, a gift from the grandmother of Israel, hidden aboard Sinatra’s jet.

In the early 1980s, Weisman built his talent management company around Sinatra, who kept Weisman busy overseeing his career and finding venues for him. Sinatra needed the work if he wanted to keep flying on private jets, frequenting the best hotels and restaurants, picking up the bills, bestowing jewelry on his wife and slipping money to friends and strangers enduring tough times. Near the end of their book, Weisman and Valoppi write: “These are the stories that are rarely told about icons, the stories of decline.” Such as the time Weisman discovered Sinatra trimming his toupée and explaining: “You can’t believe how fast it’s growing.”

Much of The Way It Was is a story of decline. For years, age had been taking a toll on Sinatra’s vision and hearing. More and more often he forgot lyrics. There were fears that weaning Sinatra off an antidepressant blamed for his memory loss would lead to belligerent fits. For safety’s sake, someone filed down the firing pin on his handgun. Retirement didn’t seem to be on the table — covered as it was by all that money.

Instead, one tour led to another and another. Sinatra was practically bullied into following through on his 1993 Duets album.

Sound wizards could sweeten the voice electronically, but a live concert was a different matter. While Weisman says he and Sinatra’s family didn’t want to see the legend embarrassed, they continued to take that chance and the concerts kept coming. On the flight home after two poor performances in Japan in 1994, Sinatra, then 79, pointed to a fellow passenger and asked: “Who’s that black girl?” It was Natalie Cole, his opening act. One more gig followed and Sinatra was done for good.

Weisman says he believes Sinatra would have died sooner than he did, in 1998, had he retired earlier, but it comes off as a rationalization for keeping the money flowing. Besides, as his manager points out, Sinatra found joy in family and friends, not just performing. Even this unique “chairman of the board” might have wished that, in the end, he’d spent more time with them and less time at the office.

Douglass K. Daniel is the author of Anne Bancroft: A Life (University Press of Kentucky).