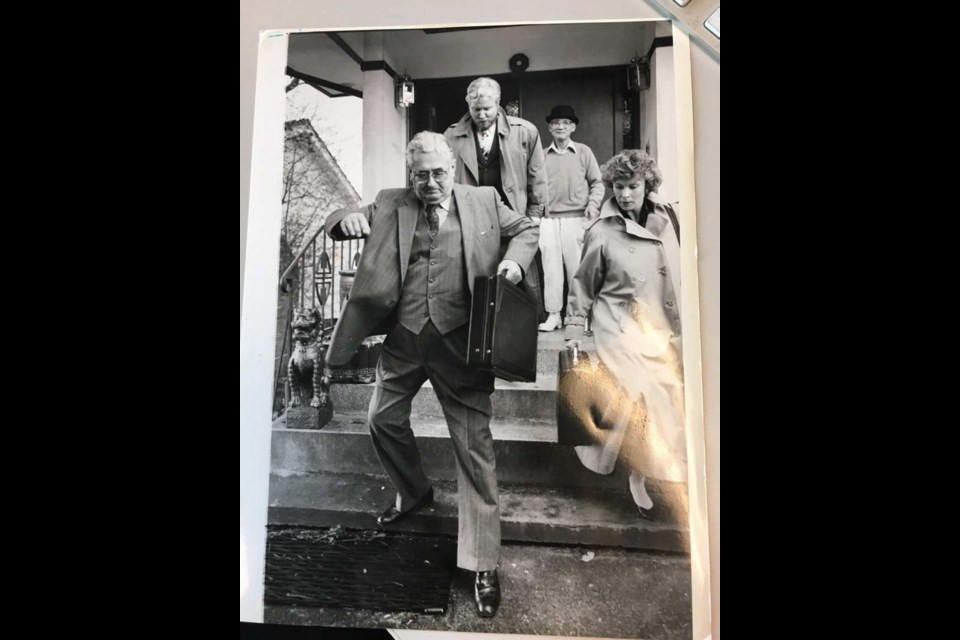

Former Saskatchewan judge Ted Hughes is widely known for becoming B.C.’s first conflict-of-interest commissioner and for bringing a new standard of ethics to bear in B.C. politics during the wild decades of the 1980s and ’90s. In this excerpt from a new book about Hughes, Craig McInnes looks back on the events that led Hughes and his wife, Helen, to leave rewarding careers in Saskatoon for a new life on Vancouver Island.

Life in Saskatoon was good for Ted and Helen Hughes in 1977. Helen was on city council. She had started the work for which she would later be awarded the Order of Canada, building bridges between the growing Indigenous population in Saskatoon and the wider community. Ted was by then an experienced judge on the Court of Queen’s Bench, steadily adding to his solid reputation for competence in the courtroom and his stellar portfolio of community service. He seemed to be firmly on a path that would keep him on the bench in senior positions until he retired, possibly still living in the town where he was born.

In March, it looked like the next step up that ladder was imminent. At the close of a conference in Ottawa, Hughes was approached by Edward Ratushny, who was then a special adviser to the federal minister of justice. Ratushny’s job was to screen potential candidates for judicial appointments. He told Hughes in confidence that Alf Bence, the chief justice of the Court of Queen’s Bench in Saskatchewan, had submitted his resignation. He wanted to know whether Hughes would be interested in the job should it be offered to him.

In a memo to file that Hughes wrote five years later, he detailed how he had been on his way home and didn’t have time for a long conversation with Ratushny. The approach surprised him. He had not expected to be under consideration for the job but would have been honoured to take it on. It was exciting news.

Hughes flew back to Saskatoon and arranged to return to Ottawa, where he met with Ratushny again, over dinner, on April 6. They talked about the conditions under which he would be prepared to serve. Ratushny made it clear others were under consideration, and Hughes commented confidentially on potential candidates.

It wasn’t the first time the two had met. As a student at the University of Saskatchewan, Ratushny had listened to Hughes lecture, and as a young lawyer in Saskatoon, Ratushny argued a case before Hughes.

Their other connection was Otto Lang, who brought Ratushny to Ottawa and appointed him to the role in which he was acting when he approached Hughes. Lang had been dean of the University of Saskatchewan law school when Ratushny was a student there. He had also articled at Ted’s firm, Francis, Woods, Gauley and Hughes, while Ted was practising there as a young lawyer, and Ted had taught courses at the School of Law while Lang was dean. Finally, three years earlier, Lang had elevated Hughes to the Court of Queen’s Bench.

In 1977, Lang was no longer the justice minister. He had been moved to the transportation portfolio. But Lang remained the political minister for Saskatchewan in the Trudeau cabinet. That meant he effectively controlled the tap at the Ottawa end of the patronage pipeline that still delivered most appointments to the bench.

By 1977, after a string of Liberal governments, most of the judges on the Saskatchewan Court of Queen’s Bench in Saskatoon and Regina were Liberal appointees, and many of them had solid credentials of service to the party. Hughes had a political background as a Progressive Conservative.

Increasingly, however, there were some exceptions, some cross-party appointments, including Hughes when he was elevated to the Court of Queen’s Bench by Lang. So when Ratushny suggested that Ted could be given a new appointment by a Liberal government, he believed he had a real chance at the job.

Three weeks later, while Ted was working in Regina, that hope started to crumble. He discovered that Bence’s pending retirement was no longer a secret. Neither was the fact that Hughes was being considered for the job.

While working alone in the judges’ library, he was approached by Kenneth MacLeod, a fellow Queen’s Bench judge who had previously been a Liberal member of the Saskatchewan legislature. MacLeod told him that he had been talking with his Liberal connections and that he, Ted, was not going to get the job of chief justice. He explained that while he was personally well liked, his previous political affiliation and his lack of service to the Liberal Party took him out of the running for such a plum post.

Hughes was shocked to find himself at the centre of gossip and what he perceived to be scheming against him by his colleagues. The next morning, he went to see Bence, who, like Hughes, was a Diefenbaker appointee, and told him that he had no stomach for what now appeared to be a nasty backroom fight over the job. He asked Bence whether he should call Ratushny and withdraw his name from consideration.

While Hughes was still in the room, Bence called Ottawa and discovered that Ratushny had gone back to teaching and was no longer in the job. His replacement told Bence that the minister’s recommendation had already gone to the prime minister, and a decision was expected within 48 hours. Under the circumstances, Bence

recommended that Hughes hang tight. So he waited.

Months went by.

Finally, on Aug. 9, 1977, the announcement was made: Frederick Johnson, a colleague on the Court of Queen’s Bench who had run unsuccessfully as a Liberal both federally and provincially, would be the new chief justice. Hughes read about it in the Saskatoon Star-Phoenix.

After the announcement, Hughes confirmed to his satisfaction what he had suspected: Some of his fellow judges with Liberal connections, and other prominent Saskatchewan Liberals, had intervened to scupper the appointment that was on its way to being delivered to him. In his 1982 memo to file, he wrote that later in August he met Lang in his Saskatoon home. Lang told him he had been obliged to intervene with the prime minister’s office on behalf of Liberals in Saskatchewan who were outraged that such a plum patronage post was being wasted on a former Progressive Conservative.

Lang remembers it differently. He wanted Johnson for the chief justice job, not for political considerations, but because he was a better candidate. “I thought that Fred was the better person for the role. He was always a person of about the most mature judgments you could ever expect. In that sense, he was miles ahead of Ted.”

Regardless of the motives behind the choice, the effect on Hughes was the same. The long weeks waiting for news of the appointment had been dreadful. He hated the sense that he was the object of gossip. For a man who had always earned accolades for his work, the notion that he was being unfairly mocked by his colleagues for what they perceived as his misplaced ambition and his naïveté was intolerable.

“I very nearly became paranoid over the thing,” he says. “I used to go over to the Bessborough Hotel and stand in the window and watch these guys at the end of a day on a Friday going over to John’s Place on the corner, and I just got the idea that they were all conspiring against me. I understand now what they were doing. But I’m just thankful that I got out and started over because I would have broken under it.”

In one sense it is odd that Hughes would have been so appalled that party politics would come into play in the appointment of a chief justice for the Court of Queen’s Bench. Even though he was no longer involved with the Progressive Conservative Party, he got his appointment as a judge through his political connections. And most of the appointments that had been made since had a strong political component.

And perhaps he should not have been surprised that others knew he was in contention for the job. He had discussed other potential candidates with Ratushny, and it seems reasonable to conclude that Ratushny had mentioned Hughes in discussions with others.

But as far as Ted was concerned, he had never asked for the job, so it was grossly unfair for others to criticize him for wanting it.

After the appointment was announced, Hughes decided his position in Saskatchewan was no longer tenable. He met with the justice minister and submitted his resignation, citing the serious damage to his credibility as a judge and his “complete lack of confidence to effectively continue in the office.”

“The environment, for me, had become so poisoned, with people not speaking to me and huddling going on, that I lost the appetite for going to work with those people,” Hughes says.

Hughes found it increasingly difficult to work in what he felt was the poisonous atmosphere of the Saskatoon courthouse. He was also developing stomach problems because of the strain, but it would be three years before he was able to leave. In the meantime, Helen had been re-elected to council in a landslide and was viewed by some as potentially the next mayor and was not so keen to leave.

“I had no choice. But I hated to leave Saskatoon. I really did. I enjoyed what I was doing there. But life is sometimes change, and you don’t have a chance to change it,” she says.

In his memo to file, Hughes described his time on the bench as “the most productive years of my life.” He would later prove that assertion false, although he could not then have predicted his extraordinary path forward.

All are invited to attend the Victoria launch of The Mighty Hughes at 7 p.m., on Thursday, Oct. 26, at Bolen Books.