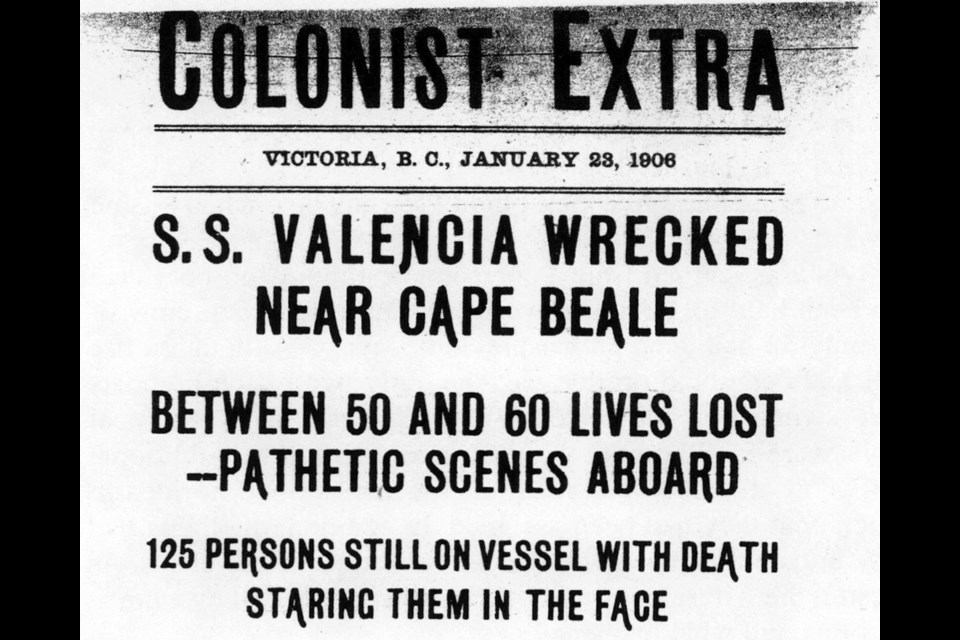

On a stormy night in January 1906, the U.S. steamer SS Valencia struck a reef off Vancouver Island and broke apart, leaving more than 100 dead and only 37 survivors. The tragedy attracted international attention and led to improvements in communications and lifesaving facilities along the dangerous stretch of coast known as the “graveyard of the Pacific.” In this excerpt from Final Voyage of the Valencia, Michael C. Neitzel recounts the first hours of the disaster, when faulty decisions were made that sealed the fate of the stranded passengers.

The Valencia first struck a rock, or ledge, a few hundred yards offshore. She hung there a few minutes. She then turned on the rock as a pivot, and came off, drifting slowly ashore in the mountainous swell. She now lay at almost a right angle to the shore, her bow pointing out to sea, and her stern only a few yards from the cliffs. This was to be her final resting place.

Her passengers and crew were marooned near the rocky shore, waves crashing against the steep cliffs. Wireless radio communication was in its infancy and was not yet available to either the ship or people on land. On this uninhabited and remote coast, there was no one to hear their cries for help. There now began a 40-hour drama, horrifying in scope.

Captain Johnson could not have picked a worse place to be wrecked. Cliffs 30 metres high dropped almost vertically into the boiling sea, each wave exploding with a roar onto the rocks, throwing spray high into the trees.

The testimony of the survivors all agreed that the stern of the steamer came to rest only about 14 to 28 metres from shore. According to reports published over the years by divers who have been to the wreck, the actual distance seems to have been from 14 to 18 metres.

Within a few minutes of the vessel grounding, soundings were taken in the bilges of the middle compartment. Water was rising in the holds at the alarming rate of one foot a minute. The captain evidently came to the conclusion that the vessel was going to sink and should therefore be beached. He informed Second Officer Petterson of this decision. The engines were put full speed astern, ramming her into the rocks, stern first. It would be over 15 hours before the outside world learned of the disaster, the Valencia and those on board left alone at the mercy of the sea. Soon after she struck, the lights failed as the generators were drowned in the rising water. The darkness heightened the panic that passengers and crew felt during these first confused moments. Spray was blowing over the vessel with each onslaught of another big wave that rammed into the disabled vessel with relentless fury.

Captain Johnson’s next order was to lower the boats to the saloon rail and lash them there. He explicitly did not want them launched at this time. What followed would be called later “a disastrous failure in the use of the boats.” And this was indeed an understatement.

The transcript of the hearing held before two Seattle inspectors on January 27, 1906, contains over a thousand pages of testimony from the few survivors. Although the testimony often differs in some detail or other, it produced the most important account of the tragedy.

At this inquiry, Second Officer Petterson gave a vivid account of what took place in the first moments of the disaster. “When she struck, we put her full speed astern. At the time the captain sung out: ‘You run and get soundings, go get the carpenter.’ ”

The Valencia managed to float free, but the damage had been done. They were at 24 fathoms and still reversing away from the deadly rocks. Captain Johnson ordered the carpenter, a man by the name of T.A. Lindur, below deck to check for water. According to Petterson, it was First Officer Holmes who came back and reported a foot of water in the hold. The Valencia was in trouble. According to Petterson:

Then the carpenter came running, two foot he said, then in a few minutes he reported six feet of water. Then the captain called all hands on deck.

Q. Was the ship backing at the time?

Backing still when the carpenter came up. The last I heard was six feet of water. He said to me: “Sing out all hands on deck.” All the people were nearly on deck when I left the bridge; come around with life preservers on them, of course, when we first struck they all jumped out of bed . . .

Captain said to me, “I am going to beach her.” That is the last words he spoke to me. Then when I run aft, there was a lot of cabbage on the hurricane deck aft when I run up, on the steps, I fell right backward on my back on the main deck alongside the main mast. [Apparently cabbage had been part of the cargo, and the crates had broken open.]

Petterson then went forward on the starboard side, where “a lot of women were.” He asked that five or six of them get into the boat he was looking after. Although these lifeboats were designed to hold eighteen people, later tests were to show that the boats could carry twenty-two, but they actually felt crowded even with eighteen on board. As Petterson’s testimony continued, the investigators learned how most of the lifeboats were lost; as was later concluded, it was mostly due to the lack of proper commands from the captain. In the darkness and confusion of the first half-hour after the wreck, no one was sure who was an officer or a passenger. As Petterson’s testimony revealed, the following thirty minutes would result in the loss of many lives.

The Final Voyage of the Valencia is available now from most Island bookstores via phone or online ordering.