I’ve kept only three souvenirs in 30 years of writing about the arts in Victoria. One is a cassette tape of an interview with singer Ray Charles. One is a postcard from humorist David Sedaris, taped to my fridge. The other is a note from Tony Bennett.

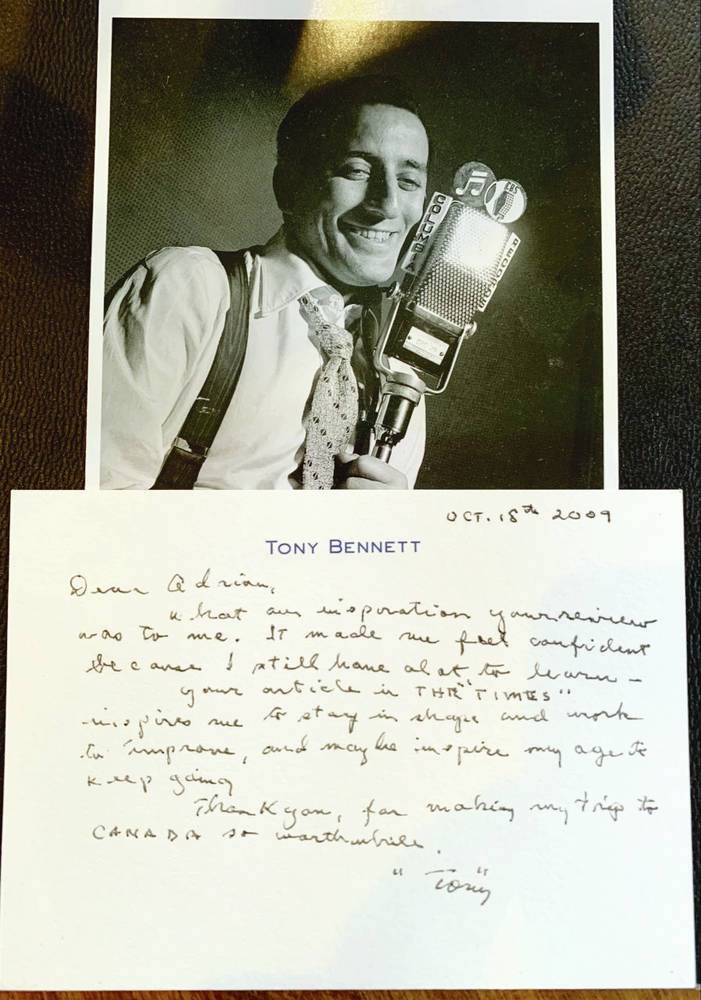

Bennett’s card is framed, under glass, and has hung on my wall for 13 years. I paired it with an old black-and-white photo of the singer in the prime of life, smiling ferociously and singing into a vintage Columbia Records mic.

This week, Bennett made headlines when it was revealed that he suffers from Alzheimer’s disease, first diagnosed in 2016. This is a sad thing. But then again, he is 94 — an old man who has lived a rich and full life.

My card from Bennett, dated Oct. 18, 2009, was sent to the Times Colonist. Twelve days previously, I’d reviewed his Oct. 6 concert at the Royal Theatre. Although emails aren’t uncommon (typically beginning with “Were we even at the same concert?”) a handwritten note is rare.

It is the size of a postcard. The paper looks expensive and is embossed, in raised blue letters, with the name Tony Bennett. The handwriting, in black ink, is spidery and astonishingly tiny. It was written with a fountain pen. The singer was 83 when he sent it.

I was surprised to receive the note. Astounded even. Bennett is, after all, among the best and most famous American vocalists of the 20th century. Frank Sinatra dubbed him the best singer in the business.

Why would he send it? The Times Colonist isn’t the New York Times or the Washington Post. We’re a mid-sized Canadian town far from Bennett’s Central Park apartment in New York City. More to the point, Bennett is a big deal — whereas I am anything but.

What he said in his note was so gracious, so generous, I initially wondered if it was sarcastic. Or ironic. Or something.

“What an inspiration your review was to me,” he wrote. He added: “Your article in the ‘Times’ inspires me to stay in shape and work to improve, and maybe inspire [someone] my age to keep going.” It is signed, simply, “Tony”.

Was he was joking? It was like Babe Ruth telling a sports commentator he appreciated his helpful feedback on swatting homeruns. I still wonder about this sometimes, although from what I’ve read, Bennett is an exceptionally humble and magnanimous man. More likely, I think he was merely being the class act that he is. A true gentleman — the kind of big-hearted fellow who takes the time to send a personally written note to the little guy.

Who does this kind of thing anymore? Especially in our buzzy electronic age, a time of hastily typed texts and emails. His card seemed old-fashioned in the best sense of the term. “Thank you for making my trip to Canada so worthwhile,” Bennett added. It reminded me of a more decorous bygone era, when people exchanged visiting cards and wrote thank-you notes afterwards.

I’d done my best with the review. However, these things are done under tight deadlines, written during the concert. They’re not exactly literature, at least, mine are not. At best, I’d hoped for a piece that was error-free and coherent. I am under no illusion that what I wrote was in any way inspirational or helpful.

I had found Bennett’s concert to be extraordinarily moving and powerful, later citing it as my favourite of 2009. My review said that the singer retained much of what made him a legend. Still, it noted his middle-register had a “reediness” at times, adding: “At best his voice boasts a manly huskiness — especially potent when he’s attacking a crescendo, as it imbues a song with emotional heft.”

Bennett was no longer the young man who’d recorded such hits as Because of You and Rags to Riches in the early 1950s. His voice was no longer subtle and smooth. There was a graininess to it. And, although his technique was still extraordinary, he didn’t always nail the high notes perfectly.

This gravelly quality appealed to me — it spoke to my personal biases. Bennett came to fame a generation before mine. I grew up on the rock music of the 1970s; my heroes were sandpaper-voiced vocalists like Rod Stewart, Roger Daltrey and Joe Cocker (influenced in turn by black R&B singers). My generation thought Sinatra and Bennett were uncool — we were wrong, of course. Our aesthetic was completely different, although I came to appreciate what I thought of as my “parents’ music” later on.

I loved — and still love — art that isn’t glossy and perfect. For me, the old leather chair, with all its cracks and imperfections, is preferable to the shiny new model. The 1952 Ford Customline with pitted, oxidized paint is superior to the concours restoration.

And so I loved — and never forgot — the late-model Bennett, still singing awfully well, despite being not quite what he had been. There was a heroicism in his urge to perform, his dedication to the art of singing, the skill and history he brought to the craft.

Like all of us, I am troubled by the news that Tony Bennett has a brain disorder that will only worsen. Still, when I hear his name, I’ll continue to think about his small act of generosity to me and how wonderful his performance in Victoria was.

At the end of his show, Bennett — accompanied by a guitarist — moved away from the microphone to sing without amplification. He sang Fly Me to the Moon. It was a tremendously affecting moment — flawed and deeply human — in the way that only great art can be.