Bing Wong had a habit of having to prove himself.

He did so as a child, as a teenager and well into his adult years.

It was rarely, if ever, by choice.

The first accountant of Chinese descent in Vancouver’s history, Wong died Aug. 5. He’s credited with helping hundreds of Chinatown businesses over a career that began in the late 1940s and only ended earlier this summer.

Wong’s family laid him to rest in a private service today (Aug. 23). His story is one of overt racism, service and resilience.

“My dad always had to fight to try to maintain partial equality,” Wong’s son Glen told the Courier.

Wong was born in Vancouver in 1924, and by age six, his family moved to Alert Bay, a tiny community located on Cormorant Island off the northeast coast of Vancouver Island.

Friends and family had previously travelled to the area to scout potential business opportunities. Recognizing that most shops were owned by whites who wouldn’t cater to anyone but, the family saw an opportunity.

At the time, Glen said Chinese weren’t allowed in some movie theatres and restaurants in Vancouver.

“The main reason [for the move] was that his father came under too much racism at that time,” Glen said. “He had other friends that had moved to the Island earlier and they told him lots of good things about the Island and that they didn’t see the racism they did in Vancouver.”

Wong’s family was one of only a handful in the area that wasn’t white. There was one Japanese fishing family, and the rest of the population was Indigenous.

The local Boy Scout troop at the time wouldn’t accept First Nations, and Wong helped change that. Numbers were lacking when it came time to field soccer and baseball teams, and in order to hit the pitch, Wong asked members of the Indigenous community to join.

“The first time they played together, my dad picked all the natives on his team,” Glen said. “The Caucasians asked, ‘Why did you pick the natives?’ The natives asked, ‘Why did you pick us, we never get picked?’ My dad said, ‘I play to win. I don’t care who you are, I want to win this soccer game.’”

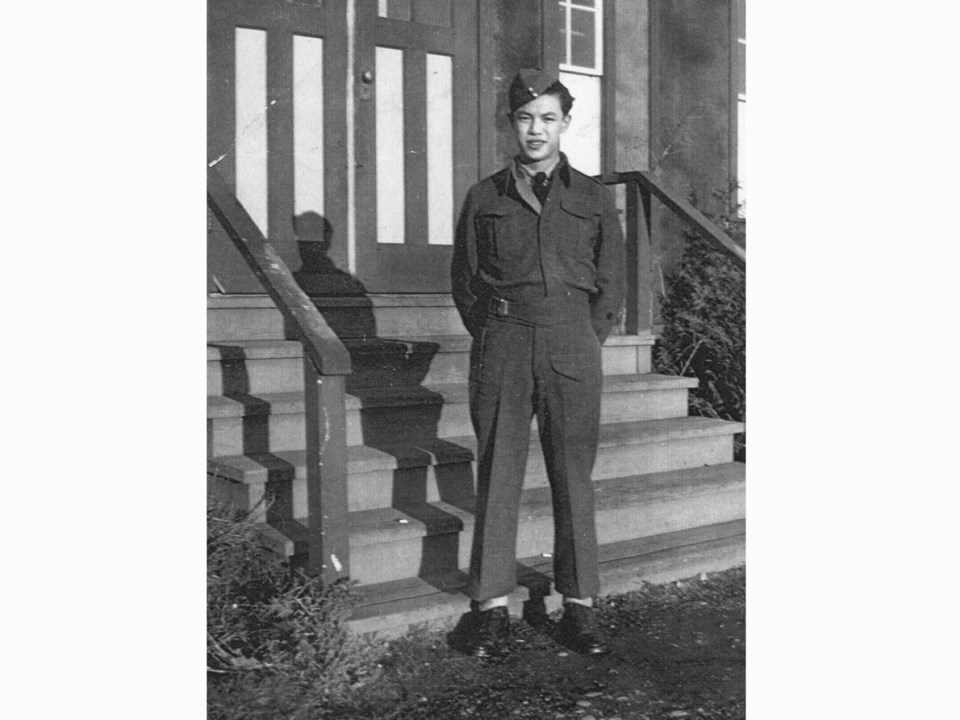

The family moved back to Vancouver by the late 1930s, and Wong was a senior at Vancouver Technical School while the Second World War was in full swing. Two-thirds of his graduating class enlisted and Wong did so as well.

“One of the things he had in the back of his mind was that this was his country,” Glen said. “He was born here and he should fight for it. He was hoping that the Canadian-born Chinese would be acknowledged for joining the army and fighting for their country.”

Wong was told signing up for the war effort immediately upon turning 18 would give him dibs on the outfit he wanted to serve with.

Wong’s preference was to fly, while his second choice was tank operator — anything but infantry, but infantry was where he ended up. Intense training in the years spanning 1942 to 1944 followed, though as the European war effort ground to a close, Wong was assigned to the Pacific theatre. He was to be part of a covert guerilla outfit that would be dropped behind enemy lines into Japanese-occupied areas in November 1945.

The land invasion would follow from there and an estimated one million Allied servicemen would die. Two atomic bombs dropped in August 1945 led to Japan’s surrender a month later.

“Luckily for me, the war ended just as they were going to send him over,” Glen said. “But when he joined the army, it was a total change. There was no racism. Everyone was treated equally. He said it was the first time everyone was treated equally for everything.”

Wong’s military service would be the last time he’d experience equality for decades. An 18-month wait for employment followed upon his return to Canada. Wong trained to be an accountant, but was told he should be a tailor or shoemaker instead.

“Finally, the solider in charge of looking for jobs said, ‘Bing you’re not going to get a job because you’re not white. No one is going to hire you,’” Glen said. “The soldier told him he had a couple friends who wanted to hire him, but the staff wouldn’t work under a Chinese person.”

Wong refused to wait and instead took his skills to the people. He began doing the books for Chinatown businesses and word spread. Wong’s hustle as a freelance accountant ended in the early 1950s, when he moved into a storefront on Main Street. Bing C. Wong & Associates Ent. Ltd. set up shop at 164 Pender St. shortly thereafter and the business remained for decades.

Glen now runs the family business, but his dad did the books up until as recently as June.

“He enjoyed it,” Glen said. “The main thing was the clientele he had. A lot of them stayed with him for 30, 40 years. A lot of them became friends.”

Wong turned his attention back to his first friends once his business was established. He went back to Alert Bay to offer financial advice to the Indigenous community, helping with everything from accounting to land purchases.

Wong also helped establish the Chinese Canadian Military Museum on Columbia Street, where a section of the museum is designated to Wong’s life.

“He did it through hard work — he was persistent and he always said you have to be honest to succeed in your work,” Glen said. “We didn’t think much of him being the first accountant until you really sit down and think about it. It is quite a big thing.”

@JohnKurucz