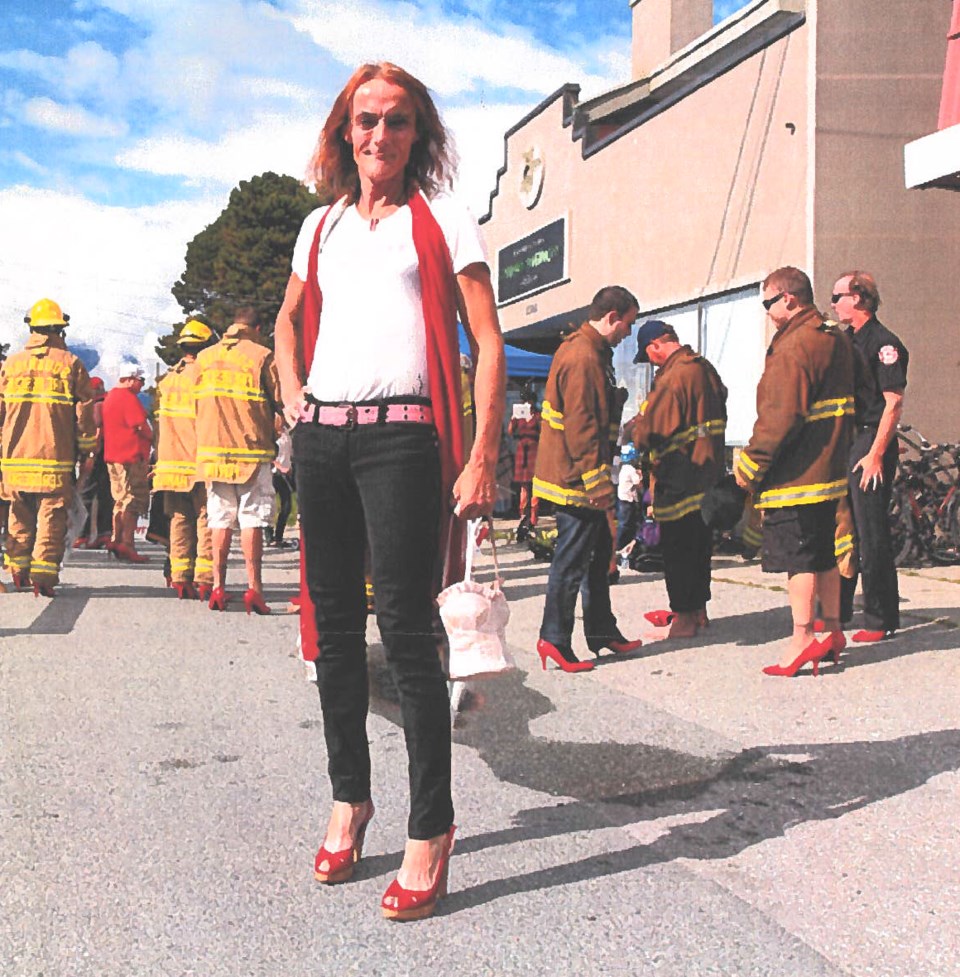

In the photo, Jayme Schmetterling looks beyond proud.

She stands in a white T-shirt, black pants with a pink belt — her red hair blows behind her. Schmetterling is carrying a pink purse, and a candy-apple red scarf circles her neck. It matches her Stuart Weitzman red high heels.

Behind her on the street in front of the Howe Sound Women’s Centre are Squamish firemen clad in their turnout jackets and red high heels.

The event was a previous Squamish Walk a Mile In Her Shoes charity event for the centre.

A hand on her hip, she looks like she feels good in her own skin.

“I used to tease the firemen and run around in my six-inch high-heel platform shoes,” she says of the photo, with a laugh.

Asked why she wanted to go public with her story, Schmetterling said, “I think it is about time.

“This town is not 14,000 people who have lived here all their lives. It is more than 20,000 people that have moved here plus the thousands and thousands of tourists we get through here and they are all fine with me.”

Schmetterling is transgender and last year was involved in an altercation in downtown Squamish that is currently before the courts. It left her with a traumatic brain injury.

“I can’t believe it happened,” Schmetterling said months later as she sat at The Ledge sipping her coffee.

She was in the hospital for 10 days and months later still deals with symptoms.

She was off work for four months.

“Everything was so overwhelming,”she said.

But Schmetterling’s story didn’t start nor end with that altercation.

Sitting at the cafe where she met with The Chief every two weeks for months, Schmetterling was constantly approached by passersby who offered a wave and a “Hello!” or who came over for a hug and a chat.

Hard to miss, Schmetterling also stands out for her outgoing nature, even since the incident that has left her a little more easily distracted and fuzzy-headed than before it happened.

It was a full life up to the point of the brain injury and has been an almost full life since.

Schmetterling began to transition when she first came to live in Squamish in 2010 when she was then a 52-year-old man.

“If a person is born with a physical defect, and they know they are disabled and built wrong... for a transgendered person, there is no difference. Our bodies were born wrong,” she said.

A difficult part of being transgender is having to constantly prove who you are, whether it be to medical professionals who are the gatekeepers to gender assignment treatments, or co-workers who challenge the gender you identify as.

Schmetterling has seven siblings, only one, her brother James, has been accepting, she said. To her mother, she will always be her childhood name, Rodney, Schmetterling said.

“That is one of the reasons I had to cut my family loose. I need a family who is going to love and support me, but every time I turned around I was at the bottom for everybody. I was like Cinderella.”

Schmetterling hasn’t talked to her daughter for eight years, though she didn’t elaborate much beyond that she also has three grandchildren she doesn’t see.

The Early Years

Schmetterling was born Rodney in Nova Scotia. Her father was an alcoholic and her parents split up when she was six, Schmetterling said.

She acknowledges she was abused sexually twice by non-family members by the time she was 12.

“When I was growing up, I had to be tough,” she recalled.

As a teenager, the boys at school thought she was gay while the girls didn’t take her seriously.

She says she tried for decades to be a man, but never felt like one.

Though they eventually split, Schmetterling married a woman at the age of 23 and they had a daughter.

In 1989, Schmetterling joined the reserves and worked all over B.C., Alberta and Washington.

She left the reserves in 1996 and was depressed for a time.

Went back to school, which she paid for with sex work, she said.

She got involved with drugs and then went through recovery.

She was also involved with search and rescue over the years.

Through it all, no matter what her outer shell said, she felt feminine.

The addictions were a way to bury the pain of early life trauma, she said.

Growing up, she had never met a trans person. The first one she met was at a recovery house.

Once she began to transition, she felt more at home.

Asked what defines her beyond transitioning, Schmetterling struggled to come up with an answer.

“For 50 years, I was defined by my masculinity and the world around me. Then, the last 10 years I have been trying to define myself again. I thought I was kind of getting there, and then with the brain injury, I am even new to myself. That is the hardest part.

“My passion has always been to live life and have an unending quest for life. And not to die in front of a TV set,” she said. “For me,

I want to go until I can’t go anymore,” she said.

What the Academic Says

Ann Travers, an associate professor of sociology at SFU and author of The Trans Generation: How Trans Kids (and Their Parents) Are Creating a Gender Revolution, told The Chief that the whole notion of binary sex and gender is fairly arbitrary, to begin with.

[Travers prefers to be referred to with the pronoun they, so that is what we do here.]

“It is one of the aspects of colonialism. European norms of sex and gender division were violently imposed on Indigenous people in Canada and the U.S.,” they said. “But it is taken for granted as normal and inevitable that there are only two sexes and that they are male and female.”

It is far more accurate to say there is a gender spectrum.

“There have always been trans people in Canada and the U.S., they just mostly stayed hidden, if they were able to.”

Travers does have some concern that medicalization is depicted as the only route to establish that you are not the sex you were assigned at birth.

There are pros and cons to the rise in discussion and popularity around gender reassignment surgery, they said.

“On the one hand, having medical documentation prevents people from legally discriminating against you. On the other hand, there are many who can’t afford or can’t access medical treatment — and there are many trans people who have no wish to. So it is kind of complicated.”

Travers said that there is an awareness among those who seek it, that there is a script that has to be followed if an individual wants to be granted medical permission to get gender treatments.

“It is very stereotypical. It is very sexist,” they said.

“Trans people have to navigate these systems and they quickly learn what you have to say, to get the treatment you need.”

Advice About Transitioning

Schmetterling said her advice for anyone who wants to transition is to “go for it.”

“You’ve got to get professional help,” she said. “Until you reach puberty, your body is going to do its biological thing.”

For youth, she says it is a very confusing time and sometimes someone may be gay and be more comfortable considering transitioning than being homosexual, so she advises making sure enough time has passed.

“They need to have a good long think about it,” she said. “I think people have to be true to themselves — it doesn’t matter what it is.... otherwise you live in other people’s confines and never reach your full potential.”

Fast Facts

Estimates suggest that as many as 1 in 200 adults may be trans (transgender, or transitioned), according to Trans PULSE research.

Stats Can data shows between 2010 to 2017, 31 hate crimes targetting transgender or asexual people were reported by police participating in the Uniform Crime Reporting Survey. Of these crimes, nearly half (15 incidents) occurred in 2017. Even though the overall number is small relative to other hate crimes, those targeting transgender or asexual people were often more violent.

In June 2017, Bill C-16 was adopted. This Bill formally recognizes protection for gender expression and identity under the Canadian Human Rights Act and the Criminal Code of Canada.

For more on gender identity and sexual orientation, including how to find gender-affirming, trans-friendly services in B.C. contact the Care Team at transcareteam@phsa.ca, visit Qmunity – BC’s Queer Resource Centre or Trans Care BC by calling 604-734-1514 or toll-free 1-866-999-1514.

Transrightsbc.ca also has an abundance of information at www.transrightsbc.ca.