I’d rather see a clever performer try an audacious experiment that doesn’t completely succeed than witness glib Canadian theatre that achieves all-too-modest goals.

That’s what I like about the Belfry Theatre’s Spark Festival. Rather than staging works that, once again, confirm the biases of nice, middle-class theatre audiences, the festival embraces risk-taking theatre capable of prodding us in uncomfortable ways.

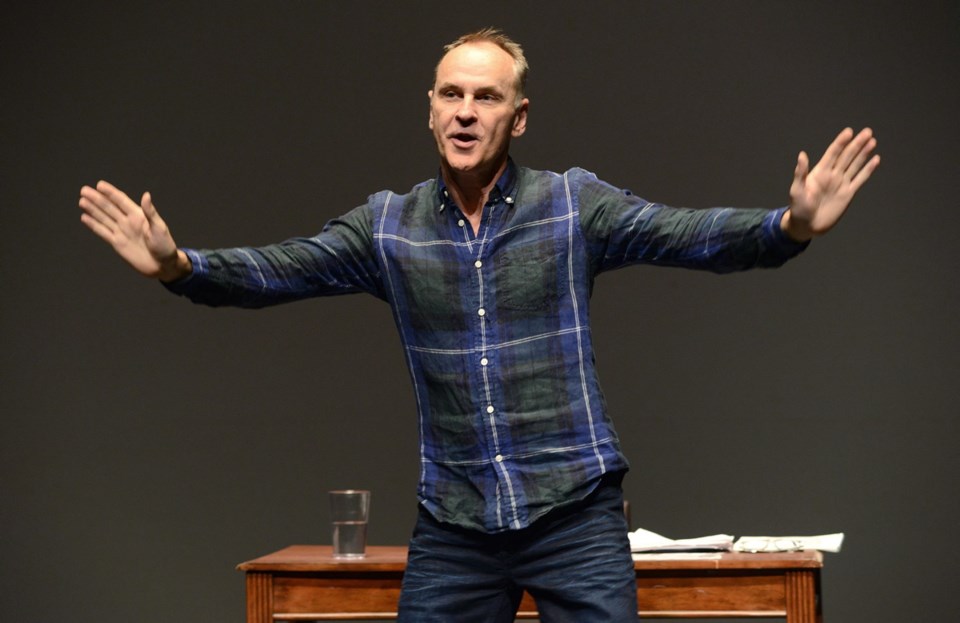

Edgy theatre sparks debate. Some people told me they weren’t crazy about Torquil Campbell’s True Crime, a Spark Festival offering I mostly enjoyed. Daniel McIvor’s Who Killed Spalding Gray?, ending its festival run tonight, didn’t quite grab me in the same way. Yet when it comes to one-man shows, McIvor is undeniably a virtuoso talent. Who Killed Spalding Gray? is intriguing, sometimes discomfiting theatre worth seeking out.

In part, Who Killed Spalding Gray? is about depression and suicide. It doesn’t sound like a laugh riot — yet McIvor instils sufficient black humour to leaven any heaviness. As with True Crime, Who Killed Spalding Gray? looks at the relationship between fact and fiction in art — a theme this Canadian actor/playwright has examined previously. Is McIvor, ostensibly playing himself in an autobiographical piece, levelling with us? Is he stretching the truth? Or is such a discussion beside the point because fiction is, in fact, the highest truth of all?

Who Killed Spalding Gray? is partly about McIvor and partly about the late Spalding Gray. Gray was the American monologist best known for Swimming to Cambodia, inspired by his experience of acting in the film The Killing Fields. Gray made international headlines in 2004 when he committed suicide by jumping off the Staten Island ferry.

With Who Killed Spalding Gray? McIvor points to similarities between his life and Gray’s. They’re both prominent monologists, although McIvor (who admits to jealousy) notes Gray was considerably more famous.

Both men identified as outsiders trying to elude personal demons. McIvor mentions his own, or at least his character’s, history of failed romantic relationships and drug/alcohol use. The latter wasn’t pretty — at one point he tells of giving his bank card and personal identification number to a crack dealer.

McIvor relates the strange tale of visiting a Californian psychic in 2004, to have a malicious “entity” removed from his soul.

Afterwards, the psychic surgeon informs McIvor he might feel discombobulated for a few years. Wandering about after the exorcism, he sees a CNN news report about Spalding’s disappearance. McIvor decides his entity removal might be connected — and, perhaps, even caused Spalding’s demise.

I found this sequence rather contrived. The notion of people ambling through life viewing coincidences as powerful signs and symbols — particularly when they involve celebrities — strikes me as silly. Of course, others will disagree.

McIvor references several trademark Spalding techniques. For instance, at times he orates while sitting at a desk with a glass of water. At the play’s beginning, he invites an audience member to join him onstage for a Spalding-esque interview, asking three questions: Who are you? Who am I? Who is Spalding Gray?

For me, the link with Gray works best when McIvor steps back from literal connections. In one scene, McIvor (as Helena Bonham Carter) quotes Tim Burton’s film Big Fish, which Spalding saw just before killing himself. The quote is something like: “A man tells his stories so many times that he becomes the stories. They live on after him. In that way he becomes immortal.” This, suggests McIvor, can be a credo for the monologist, the theatre artist — and perhaps all human beings. There’s also a whimsical tale about a suicidal man named Howard who hires a hit man to kill him because he’s too squeamish to do it himself. Capped by a surreal O. Henry ending, it’s a quirky, charming vignette — that is, as much as suicide stories can be quirky and charming.

What’s most appealing about Who Killed Spalding Gray? is the cleverness of McIvor’s confidence performance (I saw the Wednesday show) and the craftsmanship that has gone into the script.

In this play, he makes himself especially vulnerable. At times Who Killed Spalding Gray? offers a beguiling sense of hope, especially when McIvor dances to pop songs with almost heart-breaking earnestness.

Early warning: The reliably good Blue Bridge Repertory Theatre opens its season April 24 with Swan Song (and other farces), a collection of one-act plays by Anton Chekov.

The director is Jacob Richmond, co-creator of Ride the Cyclone, so expect irreverent, slightly anarchic wit. The cast includes Celine Stubel, R.J. Peters and Rod Peter Jr.

The season includes Arthur Miller’s All My Sons (directed by Brian Richmond and featuring Victor Dolhai) opening May 29, Michael Healey’s The Drawer Boy (with Griffin Lea and Gary Farmer) opening July 3 and Sweeney Todd (with Rielle Braid and Kholby Wardell) opening July 31.