Inventing Stanley Park: An Environmental History

By Sean Kheraj

UBC Press, 304 pp., $29.95

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

One of British Columbia’s great lies has to do with Stanley Park, Vancouver’s wonderful crown jewel.

Yes, I know. Recently, we saw the big celebration of the park’s 125th anniversary. The park has been a showpiece for longer than any of us have been alive, but that just means that it is high time to inject some truth into the legend.

Many like to believe that Stanley Park is a natural beauty spot, but it’s not; it has been shaped and formed and managed for the past century and a quarter. It might look more natural than the rest of Vancouver, but it is an urban setting designed to look like it’s in the middle of nowhere.

Think of it as a theme park, made to look like pristine wilderness through the careful attention of humans and machines. Want natural? Go to Mount Douglas.

Now, all of that might seem harsh. But this book — Inventing Stanley Park, by Sean Kheraj — should leave no doubt about Stanley Park. If it shatters illusions, so much the better.

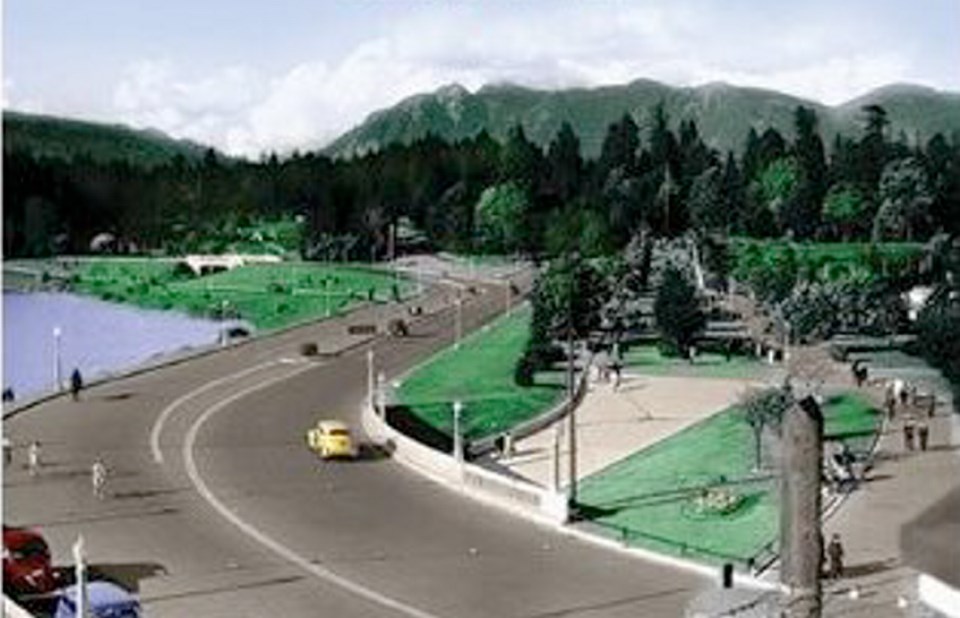

Kheraj carefully traces the development of Stanley Park and its surrounding area since the 1880s. That history includes, among other things, a residential village, a logging camp, the construction of a major highway, a seawall designed to prevent nature from doing its thing and several fierce windstorms that toppled thousands of trees.

And with every storm, people moan that old-growth forest has been lost forever. That is just not true; the old trees disappeared from the park decades ago. The 2006 windstorm was probably no worse than the one in October 1934. And let’s not forget Typhoon Freda in 1962, which also caused significant damage.

All of this is not to say that Stanley Park is not a worthy place; it certainly is. It’s the kind of park that is the envy of cities around the world.

Consider the legendary Seven Sisters, the group of trees that was symbolic of the park’s stature in Vancouver. Or the Hollow Tree, which for years was the perfect setting for a photo of your vehicle.

At times, the park has served in more serious ways. During the two world wars, part of it was used for military purposes. The book includes a photo of the four-inch guns placed at Siwash Point in 1914.

As Kheraj notes, the park would have been constantly changing even if humans had not interfered with it. The forest floor, for example, would have been littered with dead trees, ripe for occasional fires. The seawall has prevented erosion, which would have changed the shape of the peninsula.

Inventing Stanley Park is a fascinating book, sure to make readers more aware of the park’s 125-year history. It is richly detailed, as would be expected from a book published by UBC Press, with a great selection of maps and photographs.

Stanley Park is one of the most well-known features of Vancouver and — dare I say it? — British Columbia. This book will help keep it in perspective; the park is super, but it’s not natural.

The reviewer is the editor-in-chief of the Times Colonist and author of The Library Book: A History of Service to British Columbia.