It is 65 years ago, you’re 10 years old and sitting on an old, half-blind, grey horse. All you have is a saddle blanket and a rope for reins as you watch a pack of dogs rage at the foot of a Ponderosa pine.

High up on a branch, a cougar lies supine, one paw lazily swatting at the air. He knows the dogs will tire. They will slink away and then the cougar will climb down and go on with its life in the Blue Bush country south of Kamloops. It is a hot summer day. There is the smell of pine needles and Oregon grape and dust. It seems to you that the sun carves the dust from the face of the broken rocks, carves and lifts it into the air where it mixes with the sun. Just beyond you are three men on horses.

The men have saddles and boots and rifles and their horses shy at the clamour of the dogs. The man with the Winchester rifle is the one who owns the dog pack and he is the one who has led you out of the valley, following the dogs through the hills to the big tree where the cougar is trapped. You watch as the man with the rifle climbs down from the saddle and sets his boots among the slippery pine needles. When the man is sure of his footing he lifts the rifle, takes aim, and then … and then you shrink inside a cowl of silence as the cougar falls.

As you watch, the men raise their rifles and shoot them at the sun. You will not understand their triumph, their exultance. Not then. You are too young. It will take years for you to understand. But one day you will step up to a podium in an auditorium at a University on an island far to the west and you will talk about what those men did. You know now they shot at the sun because they wanted to bring a darkness into the world. Knowing that has changed you forever.

Today I look back at their generation. Most of them are dead. They were born into the first Great War of the last century. Most of their fathers did not come home from the slaughter. Most of their mothers were left lost and lonely. Their youth was wasted through the years of the Great Depression when they wandered the country in search of work, a bed or blanket, a friendly hand, a woman’s touch, a child’s quick cry. And then came the Second World War and more were lost. Millions upon millions of men, women, and children died in that old world. But we sometimes forget that untold numbers of creatures died with them: the sparrow and the rabbit, the salmon and the whale, the beetle and the butterfly, the deer and the wolf. And trees died too, the fir and spruce, the cedar and hemlock. Whole forests were sacrificed to the wars.

Those men bequeathed to me a devastated world. When my generation came of age in the mid-century, we were ready for change. And we tried to make it happen, but the ones who wanted change were few. In the end, we did what the generations before us did. We began to eat the world. We devoured the oceans and we devoured the land. We drank the lakes and the seas and we ate the mountains and plains. We ate and ate until there was almost nothing left for you or for your children to come.

The cougar that died that day back in 1949 was a question spoken into my life, and I have tried to answer that question with my teaching, my poems and my stories. Ten years after they killed the cougar, I came of age. I had no education beyond high school, but I had a deep desire to become an artist, a poet. The death of the cougar stayed with me through the years of my young manhood. Then, one moonlit night in 1963, I stepped out of my little trailer perched on the side of a mountain above the North Thompson River. Below me was the sawmill where I worked as a first-aid man. Down a short path, a little creek purled through the trees just beyond my door. I went there under the moon and, kneeling in the moss, cupped water in my hands for a drink. As I looked up I saw a cougar leaning over his paws in the thin shadows. He was six feet away, drinking from the same pool. I stared at the cougar and found myself alive in the eyes of the great cat. The cougar those men had killed when I was a boy came back to me. It was then I swore I would spend my life bearing witness to the past and the years to come.

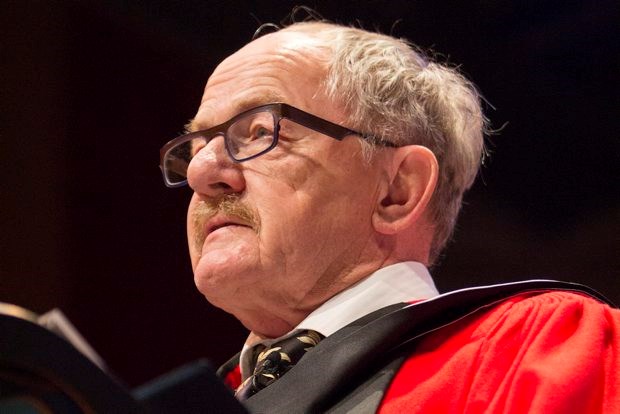

I stand here looking out over this assembly, and ask myself what I can offer you who are taking from my generation’s hands a troubled world. I am an elder now. There are times many of us old ones feel a deep regret, a profound sorrow, but our sorrow does not have to be yours. You are young and it is soon to be your time. A month ago, I sat on a river estuary in the Great Bear Rainforest north of here as a mother grizzly nursed her cubs. As the little ones suckled, the milk spilled down her chest and belly. As I watched her, I thought of this day and I thought of you who not so long ago nursed at your own mother’s breast. There, in the last intact rainforest on earth, the bear cubs became emblems of hope to me.

Out there are men and women only a few years older than you who are trying to remedy a broken world. I know and respect their passion. You, too, can change things. Just remember there are people who will try to stop you, and when they do you will have to fight for your lives and the lives of the children to come.

Today, you are graduating with the degrees you have worked so hard to attain. They will affect your lives forever. You are also one of the wild creatures of the Earth. I want you for one moment to imagine you are a ten-year-old on a half-blind, grey horse. You are watching a cougar fall from the high limb of a Ponderosa pine into a moil of raging dogs. The ones who have done this, the ones who have brought you here, are shooting at the sun. They are trying to bring a darkness into the world.

It’s your story now.

How do you want it to end?