Social conservatives believe same-sex marriage is a new and unnatural affront to traditional marriage between a man and a a woman. Liberals assume the rise of gay and lesbian weddings reflects a modern, inclusive evolution of marriage.

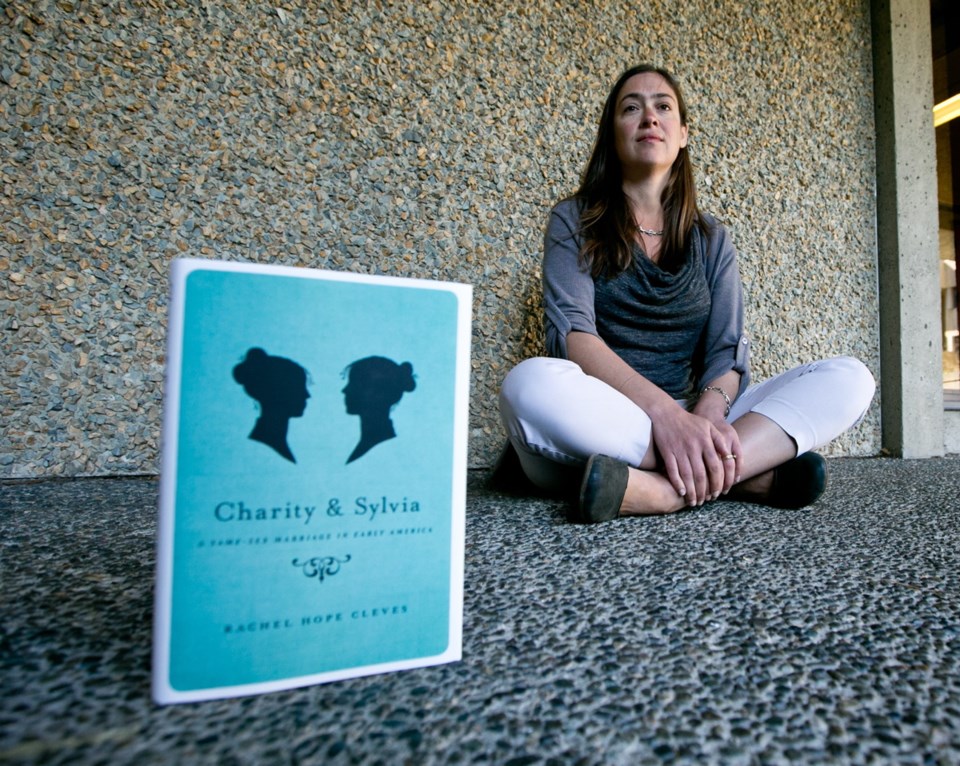

But the historical reality indicates both sides are wide of the mark, says University of Victoria historian Rachel Hope Cleves. For the past decade, Cleves has studied and compiled little-known American same-sex nuptials that date back as far as the 1500s.

“In general, our popular memory is flawed and I think that same-sex marriage is not the radical break from the past that we imagine it to be,” Cleves said in an interview.

It has a historical foundation as a minority practice, said the author of Charity and Sylvia: A Same-Sex Marriage in Early America (Oxford University Press), which details the story of a Vermont couple who moved in together circa 1809 and were viewed as married for more than 40 years by relatives and townsfolk.

The benchmark for the future will be decided at hearings starting Tuesday at the U.S. Supreme Court, which will decide whether there is constitutional right to same-sex marriage.

Cleves has sent a copy of her book to U.S. lawyer Roberta Kaplan, who will argue in favour. In return, Kaplan sent a copy of the brief she will use against the Defense of Marriage Act passed in 1995.

Same-sex marriage is legal in 37 states and the District of Columbia, allowing spouses the same benefits as for husbands and wives. But there is no federal law that recognizes same-sex marriage performed by states. The Supreme Court will decide “whether it is constitutional for states to prohibit same-sex marriage and whether states may refuse to recognize same-sex marriages lawfully performed out of state,” says the U.S. National Conference of State Legislatures.

As an associate professor of American history, Cleves challenges a pronouncement by U.S. Justice Samuel Alito that same-sex marriage is “newer than cellphones.”

U.S. historians have largely ignored the topic, despite primary sources that specify cultural if not legal acceptance of same-sex unions, Cleves said. That there were same-sex relationships isn’t as surprising as the fact those relationships were described explicitly as marriages, she said.

Although she has not studied Canada, “I would venture to guess that the history that I’ve recovered for the United States bears a lot of similarity to a history that could be recovered for Canada,” Cleves said.

The practice ranges from “wedded bachelors” among prospectors in the California Gold Rush to a 1961 survey distributed by ONE: The Homosexual Magazine that found 51 per cent of respondents were in or had been in a same-sex marriage, she writes in the March issue of the American Journal of History.

In an article titled What, Another Female Husband?: The Prehistory of Same-Sex Marriage in America, she cites:

• The earliest representation of same-sex marriage dates from 1528-1536, when conquistador Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca wrote of the custom of “one man married to another,” with one who “dressed as a woman, performed women’s work, and assumed the receptive role in sexual relations.”

• Edwin Thompson Denig, who ran the American Fur Company’s post on the Missouri River, wrote in 1855 of Woman Chief, a Crow Nation leader who took four wives.

• Newspapers across the U.S. reported the Pocomoke, Maryland murder of Ella Hearn, who spurned the marriage proposal of Lillie Duer in 1879.

Cleves’ 2014 book had its origins in a letter that famed journalist William Cullen Bryant, the nephew of the Charity in the title, wrote about his aunt and Sylvia in an 1843 edition of the New York Evening Post.

“It was a very public marriage and both of the women were understood to be women,” Cleves said. “Neither of the women were passing as men. Charity was understood to be the husband within their marriage.”

Her work on same-sex marriage is built on the research and tips of other historians, genealogists and scholars of LGBTQ history. She has also pored over documents, including historical books, newspapers and periodicals that have been digitized.

Cleves hopes her research will weave “a new kind of tapestry” that recognizes the long history of same-sex marriage and provides a framework for future work.

“One of the challenges for writing the history of same-sex marriage has been that examples in the sources are often described as being impossible or bizarre or strange, and that’s led a lot of historians as they’ve come across them to set them aside as one of a kind and not part of constituting a pattern,” she said.