Today, the Internet makes the knowledge and resources of the Royal British Columbia Museum and Archives accessible to the entire province and beyond.

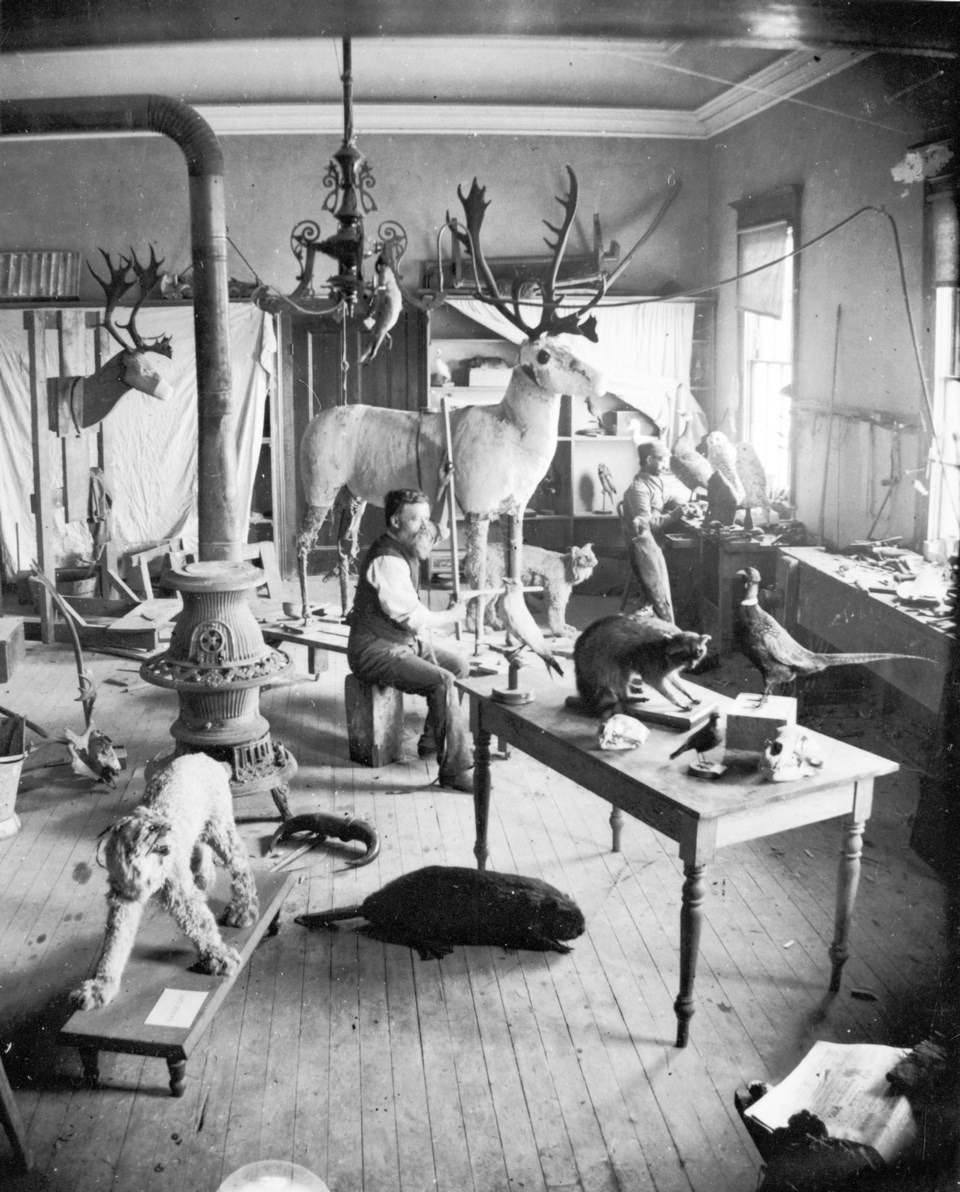

What did the museum do for British Columbia beyond Victoria before the Internet? The short answer: More than one might think. From their foundings in 1886 and 1908 respectively, the museum and archives collected flora, fauna, ethnographic material, artifacts and manuscripts around the province to display or study in Victoria. In return, they shared knowledge and resources with the province.

For decades, communication was mainly through the post office or express companies.

When public libraries were rare, the Provincial Library, from which the archives evolved, loaned boxes of books to small communities and individual volumes to students. The library continued to circulate books from its Open Shelf, but the archives stopped the practice in 1927.

A Revelstoke resident complained of discrimination but then conceded the danger of losing irreplaceable volumes. The archives, however, continued to answer mail order inquiries.

The museum received plants and animals for identification and advised people like a man in Rossland who feared losing his wife if he did not eliminate an infestation of garden snakes. The museum director suggested ways to reduce the snake population but warned him to prepare to lose his wife; snakes could not be completely eradicated.

For many years the archivist, the museum director and their staff gave public lectures in Victoria. In 1936, W. Kaye Lamb, the new archivist and librarian made a speaking tour of the Okanagan. Willard Ireland, his successor, travelled extensively giving lectures to arouse “interest in the preservation of the records of the past and in giving the people of the province a broader conception of our history.”

In the 1950s, the museum adopted this practice when Wilson Duff, its first professional anthropologist, gave public lectures and advised local museums while touring the province to salvage totem poles.

The poles were moved to Victoria, where Mungo Martin and others carved replacements for the home villages. The museum appointed a full-time adviser to visit and assist local museums in 1966. Three decades later, the museum, reversing past practice, was repatriating culturally significant artifacts to the First Nations and offering training on their care.

The museum, always interested in research around the province, launched the ambitious Living Landscapes projects in 1994, cooperating with communities to research their natural and human history; to preserve information, artifacts and endangered species; and to offer “exciting opportunities for learning.”

Studies of the Columbia River Basin and the Peace River followed a pilot project on the Thompson-Okanagan region.

From its early days, the museum hosted school tours but children beyond commuting distance of Victoria rarely benefitted. In the 1970s it experimented with “travelling kits” on marine biology, early British Columbia history, the Interior Salish and the Kootenay people for distant schools.

A teacher from the museum often accompanied the kits, which included artifacts, documents or facsimiles, photographs, films and a teachers’ guide. The response was generally favourable, but the budget could not sustain it.

The Museum Train was popular with people of all ages between 1975 and 1979. It toured most of the province accessible by rail, carrying exhibits prepared by museum curators and display specialists. Alas, repair bills for the aged steam locomotive and ancient rail cars almost exhausted the museum’s budget.

Yet, the museum remained committed to outreach through more cost-efficient exhibits such as Dragonflies, The Legacy (a collection of contemporary First Nations art work) and Echoes of the Past, which travelled to smaller museums.

After operating on an ad hoc basis, the museum formally organized a speakers’ program in 1983 that visited both larger communities and those without suitable space for exhibits. In one of the first talks, Nancy Turner, an ethnobotanist, showed slides and artifacts and provided edible samples of “wild Harvests.” In the 1990s, museum experts contributed to televised science programs produced by the Knowledge Network.

The long tradition of publishing handbooks and scientific works by museum staff and others continues. In addition, often in conjunction with major exhibitions and drawing on its own resources, the Royal B.C. Museum publishes lavishly illustrated scholarly volumes.

New Perspectives on the Gold Rush, for example, accompanied the 2015 exhibit, Gold Rush! El Dorado in British Columbia. Such books preserve research, are souvenirs for visitors, and provide knowledge and vicarious pleasure for those who did not see the exhibit. In a business plan submitted in 1991, museum director Bill Barkley observed that the public wanted more programs in more places and ones that are “technologically sophisticated [and] interactive.”

Technology has certainly enlarged the scope of travelling exhibits. In 2008, for example, the museum commemorated British Columbia’s sesquicentennial with the Free Spirit project. A museum exhibition on provincial history was only a part. Other exhibits went by rail through southern British Columbia and by van elsewhere.

People could purchase an illustrated book with DVDs of archival travelogues. A website inviting people to contribute their stories through The People’s History Project drew 3.5 million visitors.

The Royal B.C. Museum was one of the first Canadian museums to establish a website, allowing it to share treasures and knowledge beyond Victoria. By 2010, it was getting about five million hits a year. The museum has also built a presence on social media.

The archives has posted many historic photographs, some paintings of Emily Carr and other provincial artists and, to the delight of genealogists, the Vital Statistics records of births, deaths and marriages. Anyone with access to the Internet can interact with the museum. After being shown at the museum in 2010, for example, Aliens Among Us, a study of invasive species, made a two-year tour to nine smaller museums. Through an interactive website, residents could report local examples of “aliens” via smartphone or tablet.

Modern technology continues a process that dates back to the museum and archives’ beginnings — encouraging British Columbians to submit examples of natural and human history. Today, more than ever, they are institutions for all of British Columbia.

Patricia E. Roy is the author of several books on the history of British Columbia, and is working on a history of the Royal British Columbia Museum and Archives.