Kathryn Bridge has been for years the person to ask about the Emily Carr collection at the Provincial Archives.

The other day, when I met her, she seemed almost embarrassed by the grandeur of the title on her new business card: Dr. Kathryn Bridge, deputy director and head of knowledge, academic relations and atlas at the Royal B.C. Museum. She has essentially given her life to the proper appreciation of our local culture, in particular Emily Carr.

Bridge is one of the contributors to the book that accompanies the big new Carr exhibition in London, entitled From the Forest to the Sea (Dulwich Picture Gallery until March 9). Her essay identifies loans from Emily Carr’s “well-travelled steamer trunk” into which the artist packed “all that seemed most precious to her: journals recording her thoughts, the manuscripts of her life adventures, letters that documented important friendships and confidences, books of poetry and inspirational thought, mementos from her early life and travels, and a handful of small sketchbooks containing her recent work.” This is the very material that has been in Bridge’s care since about 1975.

She’s still bubbling with excitement from the London show, a special project of Ian Dejardin, director of the Dulwich Picture Gallery, and Sarah Milroy (best known as the art writer for the Globe and Mail). Milroy made the choices and wrote the lead essay — “it’s her baby,” as Bridge told me.

The first event of the four-day “opening” was a sit-down dinner for 300. This took place in the main gallery with paintings by Gainsborough and Renoir on the walls, and everyone seated at one exceptionally long table.

“It was just unbelievably lovely,” Bridge recalled, “with 10 or 12 footmen who set down the plates at a secret signal, all served at the absolutely identical time. It was magic.” After dinner, Haida dancers brought drums and eagle down to lift the event into the stratosphere.

The next day featured a cocktail party for the cognoscenti of the metropolis, and the day after that a seminar presented by all the contributors took place from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. The theatre was sold out well in advance, with tickets at 40 pounds each.

The following day, the Carr paintings — about 150 of them— were at last open to the public. All the big national dailies reviewed the show, and Our Dear Emily was placed in the company of Van Gogh. Richard Dorment of the Telegraph put it in a nutshell: “You’ll never have to ask who Emily Carr is again.”

In 2013, Bridge had spent a month doing research in England. Carr’s time there from 1899 to 1904 has now been properly looked into and Bridge’s discoveries are presented in her latest book, Emily Carr in England (Royal B.C. Museum, 2014). The book fills in the gaps in Carr’s beloved stories and provides complete facsimile versions of Carr’s “funny books,” for a while in England Carr produced a series of paintings on paper, with poems. These autobiographical stories are essentially graphic novels.

In her book, Bridge sets the stories in a richly detailed context. This is her second book in this format, the first one being Sister and I: From Victoria to London, which is mostly given over to a facsimile version of the longest of Carr’s “funny books.” (Last year, Michael Ostroff, director of the finest of all Carr films, Winds of Heaven, gave me his copy of Sister and I in Alaska, a diary of her trip to Sitka, Skagway and Juneau, privately printed with an introduction by David Silcox. In that volume, Silcox wrote that Victoria to London was “a great assistance and model for me.”)

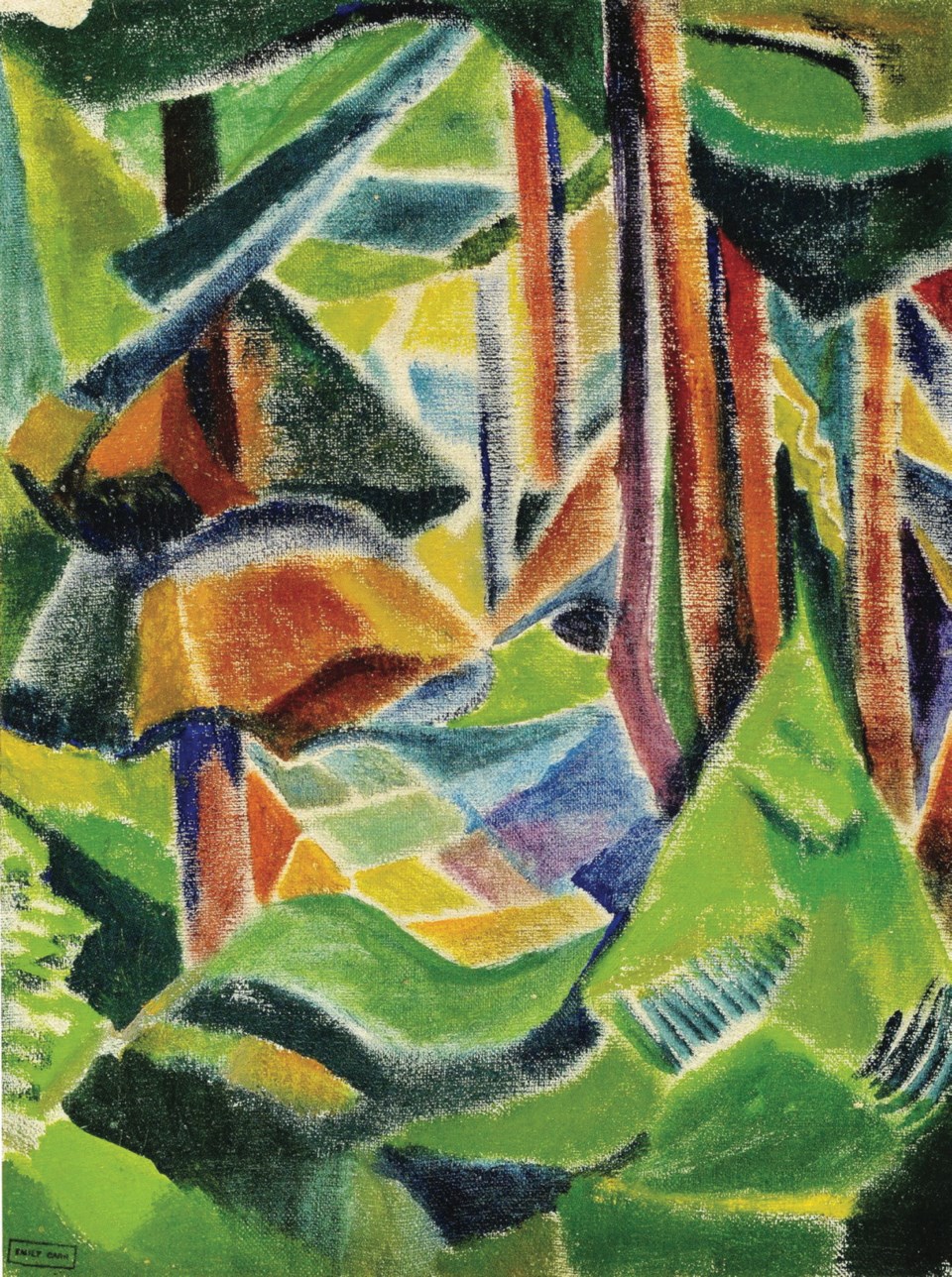

The new catalogue from the Dulwich Gallery is notable for the fine reproductions of Carr paintings both early (from her sketchbooks) and late (the forests and trees of the 1930s). The short essays are wide-ranging and aimed at a general audience. Regrettably, this book is not yet available in Victoria — a serious oversight.

A version of the show will be coming to the Art Gallery of Ontario next year (April 11 to July 12, 2015) with a similar wealth of paintings. The current exhibit includes 36 paintings from the Vancouver Art Gallery (which holds her Emily Carr Trust Collection), 20 from Canada’s National Gallery, and 47 items from the Royal B.C. Museum in Victoria (much of it from her notebooks and sketchbooks). In addition, this generous selection includes 22 paintings from private collections and brings together choice examples from most of Canada’s other art museums. Adding depth to the show are exquisite First Nations artifacts from England’s British Museum, the Horniman Museum and Pitt Rivers Museum, as well as the University of British Columbia.

I pressed Bridge for news of the RBCM’s ideas for our Carr collection. Plans are being developed to clear out the gift shop, cafeteria and front hall on the museum’s main floor and to install a new welcoming entry. This will include an intimate “jewel box” gallery dedicated to Carr.

“There’s not much more I’m allowed to tell you,” she hesitated. But she did admit that it will be “a space which will have Carr out there on a permanent and rotating basis, with two floors and a study centre for Emily Carr.”

We agreed this had been a long time coming.

“The RBCM will attempt to present the whole story of Carr in the context of her time and social situation through our collections,” Bridge explained.

Emily Carr is Canada’s best-known artist worldwide, and her powerful paintings and extensive writings are all about this place. It is not given to every town to have an iconic painter and writer who lived and worked in its midst. In Victoria, we must create new ways to honour her in her hometown.