I got my start as an art historian when Don Newell-Smith, then volunteer registrar of the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria asked if I had seen a painting titled L’étoile, by Mary Riter Hamilton (1873-1954). It was noted in his leather-bound ledger book as part of the gallery’s collection, but he couldn’t find it. As a junior employee at the gallery, I kept my eyes open for it, and looked up the artist in the Dictionary of Canadian Artists.

I got my start as an art historian when Don Newell-Smith, then volunteer registrar of the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria asked if I had seen a painting titled L’étoile, by Mary Riter Hamilton (1873-1954). It was noted in his leather-bound ledger book as part of the gallery’s collection, but he couldn’t find it. As a junior employee at the gallery, I kept my eyes open for it, and looked up the artist in the Dictionary of Canadian Artists.

Hamilton was described in a paragraph as having lived in Victoria during the Great War, following which she went to paint the battlefields in France between 1919 and 1923. My appetite was whetted.

A CBC Radio producer heard about my search for the “unknown artist” and interviewed me, which led me to visits with elderly people who had met Hamilton as a child. Eventually I found enough of her work to put on an exhibit and, in 1978, published a little book. L’étoile was found — it’s a tiny wooden panel showing Place d’étoile in Paris. I was fascinated by the detective work.

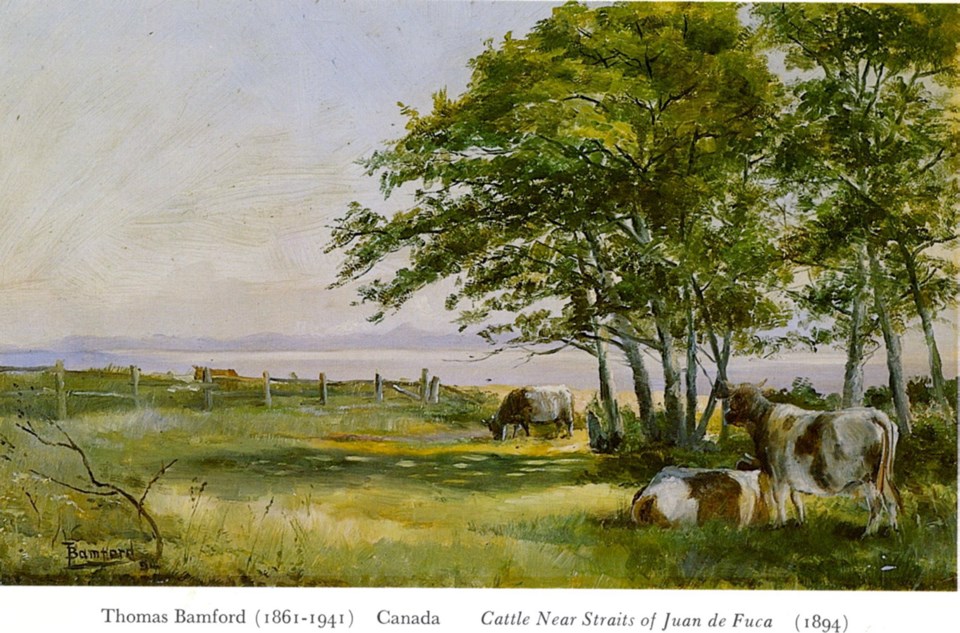

At about that time, Jim Nesbitt, redoubtable journalist for this newspaper and the saviour of Craigdarroch Castle, noticed my taste for history and suggested I learn about Thomas Bamford (1861-1941). “Everybody had a Bamford,” he told me. “They got them as wedding presents.”

My hunt for paintings by that artist — a civil servant who lived across the street from Emily Carr — turned up about 60 paintings of Victoria landscapes from 1890 to 1930. I met family members who brought out long-hidden treasures and asked me to be keynote speaker at a family reunion. The show shone a light on an artist who, since his death, had never been seriously considered.

In the 1980s, when I began writing this column, my doctor introduced me to one of his elderly patients.

Her father, Arthur Checkley (1871-1945), had been part of the Island Arts and Crafts Society and she had more than 250 of his paintings in her garage. I sensed that she couldn’t die in peace until she had done something with them to establish his reputation, and so she retained me to deal with them.

I combed through his scrapbooks, interviewed her at length, sorted and photographed all the paintings and arranged to deposit the best of them in the Provincial Archives and the art gallery. My specialized skills as an art detective were growing.

Through all this time, I cultivated my interest in Harold Mortimer-Lamb (1871-1970), father of Molly Lamb Bobak (who became a more famous artist than her father). Mortimer-Lamb had been Canada’s most famous Pictorialist photographer, beginning in Victoria in 1895.

After his death in 1970, he left his art collection and his papers to the art gallery here.

I read all his letters (from Emily Carr, Fred Varley, Lawren Harris and many others) and identified the subjects of the 265 photographs and numerous picture albums he left behind. I hunted down paintings and photographs made by him, or owned by him, or of him, many of which were languishing in museums and private collections across the country. Eventually, this work was displayed at the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria in 2012 and the book was published. His granddaughter called me “our family’s biggest fan.”

I met abstract painter Margaret Peterson (1902-1997) during the later years of her life, and after her death talked to Colin Graham, her former student and first director of the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, who was her executor. He did his best to place her magisterial paintings in important institutions. Years after his death, I learned that he had left in storage 16 boxes of her papers, dusty and unopened. They were soon deposited at the University of Victoria’s Artists Archives.

There, I spent a year poring over the boxes. I seemed to sense Peterson at my back, gently encouraging me to take responsibility for her reputation and connect the dots of her life story.

She had simply tossed everything in those boxes — unpaid bills, old magazines and unused paints. There was a collection of her love letters (written as she rode across the continent on the Santa Fe Superchief in 1933) each in its original envelope.

A sense of immediacy comes from sorting through someone else’s property. Slides and snapshots of Peterson’s art career were mixed with thousands of pages of manuscript, the text of five books she never quite finished writing. My work was to sort and understand her creations, and I’ve had the pleasure of reading her biography up close and personal. Students after me will find the trail easier to follow, and perhaps some day will write her biography.

At the moment, I am deeply involved with the papers of E.J. Hughes (1913-2007) which have been carefully saved by Pat Salmon. Hughes, a legendary painter from Shawnigan Lake and Duncan, referred to Salmon as his “friend, biographer and chauffeur.” She spent 40 years collecting material for the definitive book about him, and gave me the task of assembling the pieces.

Though a book might result, for now my real pleasure is in bringing chronological order to the images, sorting letters according to postmark and slowly reading through the events of the life of an artist I greatly admire — in his own words.

This opportunity might never come again. How long has it been since you received a letter with a postmark, written in the author’s revealing handwriting on carefully chosen stationery? Have we seen the end of all those boxes of photographs — and more importantly, the negatives — in every print format, with names and dates written on the back?

We are told that every word we speak and every step we take is now subject to eternally recorded surveillance. What will be left of that material for those who come after us, to help them understand? Are your papers in order?