The long-awaited book Pat Martin Bates: Balancing on a Thread has been published. Author Pat Bovey’s labour of love for eight years, it is worth the wait.

The long-awaited book Pat Martin Bates: Balancing on a Thread has been published. Author Pat Bovey’s labour of love for eight years, it is worth the wait.

Of particular note are the many sensitive and revealing photographs by John Taylor of the art, which is often white-on-white or black-on-black, pierced by the artist with a multitude of pinholes and lit from behind. Bates’s curriculum vitae runs to 21 pages and offers undeniable proof of the esteem in which she is held by her peers worldwide.

Bovey’s text, based on numerous interviews and her thorough knowledge of the field, will surely become the standard reference for this artist, whom many call “Lady Print.” Abundant quotations by the artist and her associates illuminate this thoughtful and straightforward text. Everywhere is evidence of a sincere effort on Bovey’s part to bring us the story, the art and the artist’s words.

That said, the inspiring battiness of Pat Martin Bates — dressed with glamour, apt to break into song, flitting from one interest to another like a firefly — can never be captured within the pages of a book.

Pat Martin Bates: Balancing on a Thread, by Patricia Bovey, Frontenac House, Calgary, Alta., 192 pages, $50.

The front door of Bates’s home and studio has a unique stained-glass window showing her initials in black and white, created by Kerry Joe Kelly. Kelly died recently in Portugal where he had lived with his wife, Diane, for many years.

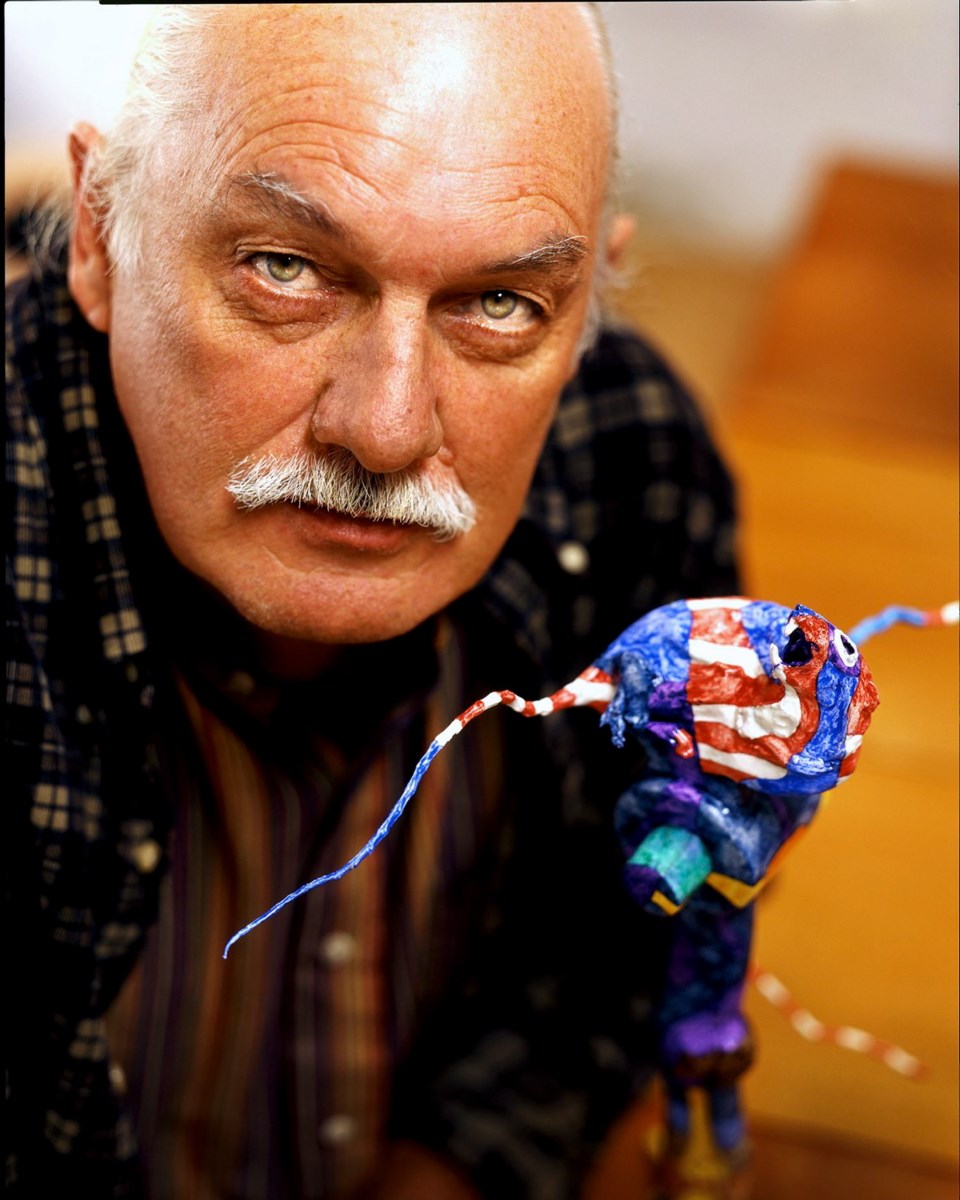

Kelly worked on the creative edge of the stained-glass field. Over the years, he cut up anything made of glass, assembling and refashioning the pieces in a way that expressed his strong political opinions.

Inspired by artist Jack Kidder and his companion George Forbes, in 1975 Kelly received a contract for 25 glass panels for the provincial government’s Rithet Building on Wharf Street and in the following year had solo shows at the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria and the Bau Xi Gallery. His work entered the Provincial Art Collection at this time, and in 1986 he created a huge installation for the Folk Life Pavilion at Vancouver’s Expo ’86.

Kelly had an unbreakable attachment to Victoria. After all, his great-great-grandfather, “Long Gun Jack,” wrote a memoir of the early days in Fort Victoria. The extended family settled at Cordova Bay, two doors south of the former McMorran’s, and Kelly attended Bank Street and Margaret Jenkins Elementary, as well as Oak Bay and Victoria high schools. After studying chemical engineering and working for Imperial Oil in Sarnia, in 1969 he tossed it all aside, riding his motorcycle back to Victoria to become an artist.

In the late 1980s, after creating a dramatic circular window for Swan’s Pub, Kelly and Diane headed for Portugal, where he found abundant work creating installations for churches, office towers and private residences. Unquestionably, his major creation was a screen at the entrance to the new Basilica of Fatima, a major Catholic pilgrimage site with an auditorium that seats 9,000. His glass wall is 37 metres across and four metres tall, etched with words of the Bible in 27 languages.

A musician and composer, Diane Kelly accompanied her husband on their frequent returns to Saltspring Island and to Victoria, but Portugal always drew them back. She was with him there when, on May 20, he suffered a stroke and died.

In the fine new book on J. Fenwick Lansdowne, I read the words of Robert Genn. “I met Fen in 1950. I was 14 and he was 13. Our parents somehow arranged that we should get together. Birders were thin on the ground in those days, especially in Victoria.” Lansdowne died a few years ago, and now so has Genn.

Robert Genn was born in Victoria in 1937, and attended Doncaster School, Mount Douglas High School and Victoria College, graduating in 1953. After an excellent practical education in industrial design at the Art Centre School in Los Angeles, he brought his precocious talent for painting to Vancouver and later settled in White Rock.

Perhaps too popular for the refined atmosphere of institutional galleries, Genn created some of the most striking Canadian landscapes ever painted, as his many admirers in the Federation of Canadian Artists would agree.

He loved to paint on location and, back in his studio, Genn mixed and matched his motifs in a bold and confident way. “Nature is usually wrong,” he told me. “Reorganize it!”

Masterful in technique, Genn designed in bold shapes, painting them with unique colour relationships. With incisive brushwork, he carved the negative spaces between tree branches in ways many envy; his finished compositions were sometimes accented with a confetti of bright spots, applied like acupuncture to pressure points of the design. His paintings have for years been available locally at The Gallery in the Oak Bay Village, 2223a Oak Bay Avenue.

While supplying an eager market with artworks, he also wrote widely. His book Love Letters to Art (Studio Beckett Publications, Vancouver, 2008) is a pairing of his remarkable paintings with some of the notes and articles he posted online over the years in his Twice Weekly Letters. These letters — candid, well-informed and concerning the things real artists think about — made him hundreds and thousands of friends worldwide.

One thing I will never forget is Genn’s homemade chair/easel arrangement. He was using Mark VIII the last time I saw it. Based on an aluminum folding chair with a foam seat cushion, it incorporated a removable aluminum easel/tray. The contraption looked strange, but he could sit and paint in comfort for hours, on no matter what mountain ridge or fishboat dock. Quirky, paint-spattered and intelligent in its unique design, it was a lot like its designer.

Robert Genn died on May 27 of pancreatic cancer in his hometown, White Rock.