What: Ballet B.C.

Where: Royal Theatre

When: Nov. 13, 14

Rating: 5 out of 5

Vancouver’s Ballet B.C. tackled big themes when it visited Victoria this weekend. Life, death, rebirth — it was all there in a pair of energetic, accomplished performances from this talented company.

The finale of Friday’s show was Solo Echo by Crystal Pite, the Victoria-raised dancer who’s achieved international notice as a gifted young choreographer.

Solo Echo is set to two works for cello and piano by Johannes Brahms; the first an early piece, the other a late composition. A touching rumination on mortality, a melancholic mood is set by a fall of faux snow wafting down throughout the work. It’s a simple theatrical device but a powerful one, infusing Solo Echo with a sense of wonder and finality.

The first Brahms is the allegro movement from Cello Sonata Op. 38. The music is dramatic and deeply romantic. Dancers, dressed more or less in black street clothes, conveyed a playful athleticism suggestive of youth. There’s a repeated motif — the dancers are seen in a running motion, straining to get ahead. This section had a contained vigour, somehow suggestive of ambition and idealism.

Solo Echo’s second segment is set to the adagio from Brahms’ Cello Sonata Op. 99. There are similarities with the first piece; however, the music is romantic in a different way — the cello sounds like it’s sobbing.

The unforgettable image here was a cluster of seven dancers, lined in unison, moving in a way reminiscent of a caterpillar or a centipede. This configuration suggests a single being, with each dancer representing an aspect of the person.

The running motif is reprised. But this time the movement is much more conflicted. Dancers yanked themselves and each other; youth’s vigorous confidence seemed to have eroded. In one powerful sequence, a man — his mouth forming a silent scream — is raised aloft by the group, only to be pulled back and engulfed by this swarming mass.

This level of excellence, both in choreography and performance, was retained throughout the night, which ended in a standing ovation. The evening began with Twenty Eight Thousand Waves by Cayetano Soto. It’s built on a simple idea — Soto was inspired by the fact seaborne tankers are struck by 28,000 waves a day on average. His dance is about life, death, survival and the cycles of life.

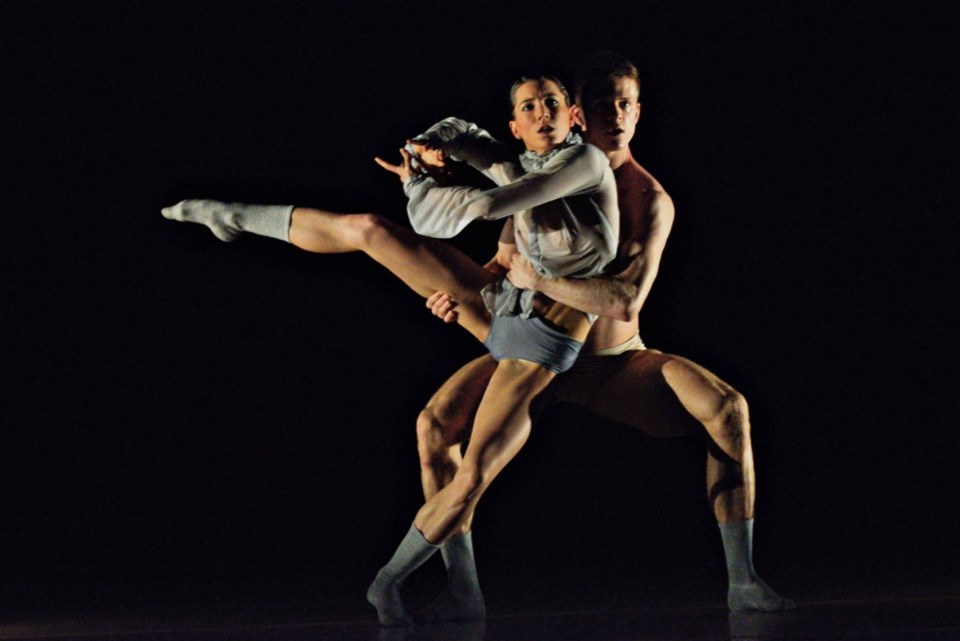

Part of the music Soto uses is David Lang’s We Sit and Cry; I Lie from The Little Match Girl Passion. A sparsely orchestrated piece, dominated by hypnotic vocal harmonies, We Sit and Cry; I Lie is constructed around quirky, slightly off-kilter rhythms. The dance reflects this perfectly — the opening section is replete with unusual (and unusually challenging) lifts that appeared effortless. There was sense of controlled energy, bodies typically interwined sinuously.

Soto then upshifted with Bruce Dressner’s Ayem, which commences with relentless string figures. Six male dancers in kilt-like skirts struck sculptural poses underneath bold, almost blinding lights. The dance had razor-cut precision; it was compelling and energetic.

Twenty Eight Thousand Waves offers repeated waves of patterns in duos and larger groupings. The dancers performed like their lives depended on it — the intensity and calibre of execution was wonderful.

No less thrilling was Awe by Stijn Celis. It is danced to liturgical choir music by Piotr Janczak and Carl Orff as well as secular music by Eriks Esenvalds, set to Leonard Cohen’s poetry.

Awe begins with a simple scene — a lone man on his knees. He is working, perhaps stirring something. The man seems tormented, at odds with the heavenly a cappella choir accompanying him.

The dance progresses with pairs and trios. The dancers, dimly lit, wore dull-looking street clothes. There was a sense of ordinary people doing the ordinary things that are the stuff of life. At the same time, Awe radiated a sense of sacredness, as though each movement was, in itself, a small miracle.

In a key scene, the dancers moved in a separate, diffuse manner, only to abruptly regroup, moving heads lowered in a perfect, spinning circle. Like Soto’s offering, Awe is notable for its difficult and unorthodox lifts — at one point, a female dancer was rolled up over another dancer’s lap and waist.

Ballet B.C., thriving under artistic leadership of Emily Molnar, is obviously operating at the top of its game. This was invigorating, beautifully rehearsed dance performed to a deeply appreciative crowd.