A recent study by the McKinsey Global Institute found that at least one-third of workers in most occupations can be replaced by robots. That translates into 800 million lost jobs, worldwide.

In the U.S., according to McKinsey, 70 million Americans could become casualties to robotics, artificial intelligence and machine learning by the year 2030. The equivalent figure for Canada is about eight million jobs — in both cases, roughly 30 per cent of the workforce.

It might be thought the introduction of such revolutionary technologies would generate enough new employment to make up the difference. But that is not the conclusion of the study. Its authors estimate that about 365 million new jobs will indeed be created around the globe, yet this leaves a huge shortfall roughly equivalent to that.

In effect, hundreds of millions will have to retrain for different forms of employment, and that is not a simple proposition. The main impact of robotization will fall, at least initially, on those least able to cope with a career change — employees who perform physical or routine tasks, and whose employment requires limited education beyond high school.

Since it is implausible to suppose the majority of these workers will successfully make the transitions required, we must assume that if steps aren’t taken to slow the tide of robotization, many will be forced to leave the workforce entirely.

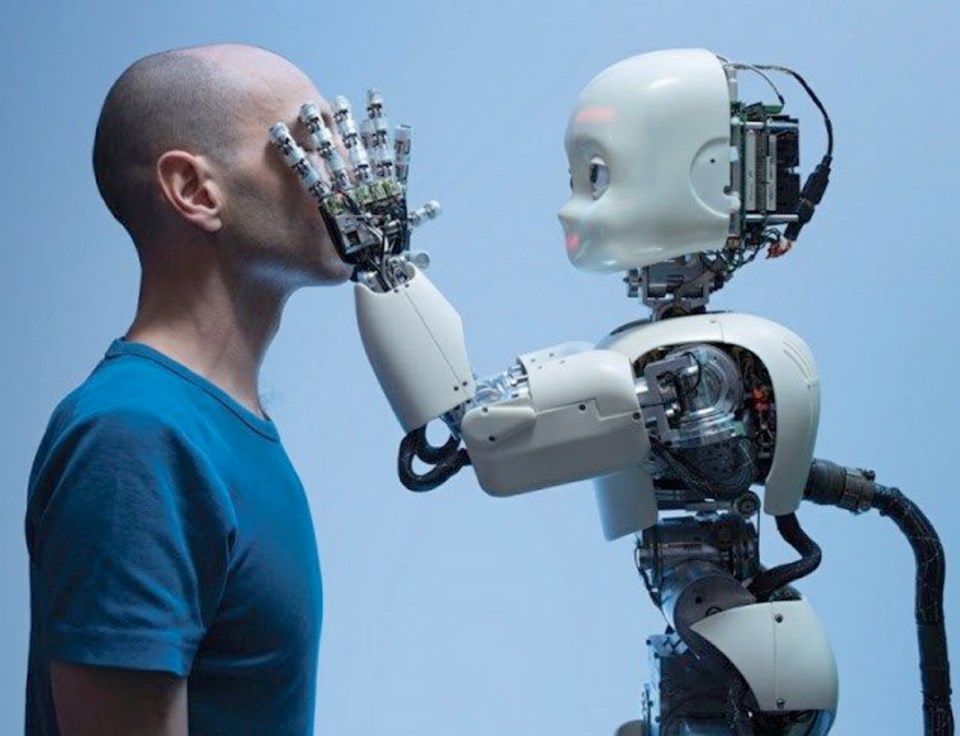

But the automation of physical labour is just the start. There are opportunities for smart machines to carry out much more sophisticated tasks. Bond trading and some aspects of accounting are viable fields for artificial intelligence. Algorithms have demonstrated a superior ability to detect profitable patterns in large stock-market databases.

Computers can already scan laboratory test results and some medical images both far more rapidly, and with greater accuracy, than humans. Robots have been designed that can diagnose some neurological disorders merely by “listening” to voice recordings from patients. They can also diagnose some forms of cancer with more precision than oncologists.

And the da Vinci robotic-surgery system can assist in the removal of prostate tumours with fewer downstream side-effects for the patient.

In short, once this revolution gets rolling, it’s hard to see where it ends. The question is what should be done.

The answer, I think, is that public opinion must be mobilized to demand safeguards for human employment.

There’s a ton of research showing that job loss is associated with stress and depression, particularly among older workers. Psychologists consider employment a key factor in helping to preserve our sense of self-worth.

It might be argued that governments could compensate displaced workers with some form of guaranteed income. But even if this could be afforded, it isn’t charity that creates a sense of fulfilment, it’s work.

Research from Sweden backs this up. Guaranteed incomes don’t compensate for the loss of human dignity that comes with unemployment.

I doubt we can count on politicians to take the lead here. They would be confronting the world’s business tycoons.

It’s going to be up to us — and in particular blue-collar workers — to demand that this threat be faced. And we need an international movement. No single country can go it alone.

It’s conceivable that eventually bodies such as the Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development could be convinced to outlaw job-killing automation.

But for now, the ball is in our court. This is a matter that trade unions could help with. After all, their members’ jobs are on the line.

We took up arms during the Industrial Revolution to protect workers from the dangers of mechanized workplaces. It’s time to do so again, and the cause is more critical — the very right to employment is at stake.