Victoria connections — including a possible romance — can be found at the upcoming Royal B.C. Museum exhibition of the quest to be first to the South Pole a century ago.

Central to the five-month exhibit — Race to the End of the Earth, which opens next Friday — is the contest between two polar explorers: the winner, Norwegian Roald Amundsen, and his doomed competitor, British Navy Capt. Robert F. Scott., who not only lost the race by weeks, but died with his four men.

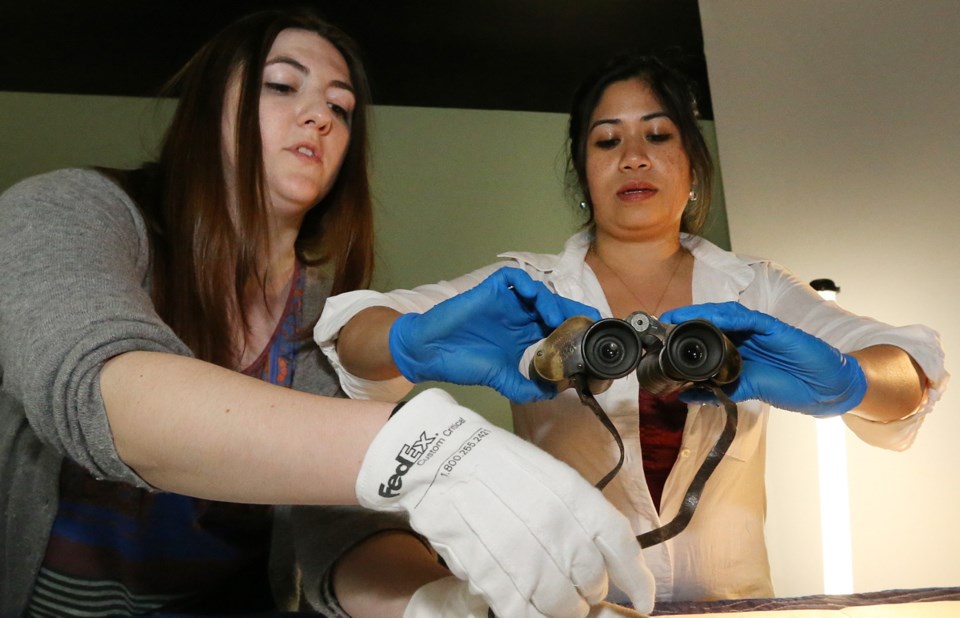

Much of the show has come on loan from the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

But the Royal B.C. Museum has turned out letters and papers in its collection with hints of a romance between Scott and Kathleen O’Reilly, a prominent young woman of late-19th-century Victoria society.

At the time, Scott was only a lieutenant in his early 20s aboard the HMS Amphion and stationed at Esquimalt from 1889 to 1891.

The museum has O’Reilly’s dance cards from parties of the time, and they are filled with Scott’s name for waltzes and polkas. They also have subsequent letters written to the O’Reilly family.

Ann Ten Cate, museum archivist, said the dance cards and letters are not proof of a romance between the two, “but it’s fun to speculate but I don’t think we’ll ever know,” she said in an interview Wednesday.

Scott later married Kathleen Bruce, an English sculptress, and the couple had one son.

O’Reilly, meanwhile, never married and died in 1945 at the age of 78, and her papers were found at Point Ellice House, now a historic site.

Race to the End of the Earth focuses on the race between Scott and Amundsen. Artifacts and replicas will demonstrate the differences between the two and offer insights into the conditions they faced.

Back then, nobody had ever reached the South Pole. It was so alien, a trek to Antarctica was almost like going to the moon.

Tim Willis, museum vice-president of visitor engagement, said Scott, by then a naval captain, attacked the quest with a kind of military zeal and English sensibilities. He worried about his sled dogs and arctic ponies and insisted on collecting scientific samples.

Amundsen, meanwhile, focused only on being first to the South Pole. He took along only dogs, and even ate one or two. He also relied on techniques and gear he adopted living among the Inuit of the North Pole in years prior.

“It’s a very dynamic story between two men who could not have been more different,” Willis said at a media preview Wednesday.

Amundsen’s approach ultimately proved successful. Scott and his party reached the South Pole on Jan. 17, 1912, after a trek of nearly three months. But they found a Norwegian flag planted there by Amundsen’s party on Dec. 14, 1911.

On the trek back, two of Scott’s men died. Scott and two other men were later trapped in a blizzard in their tent, with no food and no fuel.

On March 29, Scott made his last record in his journal. On Nov. 12, a search party find the three frozen in their sleeping bags.

Scott has since been transformed into a tragic hero, immortalized in the 1948 movie, Scott of the Antarctic, where he is played by English actor John Mills.

And the fascination with the polar expeditions and its members continues.

Times Colonist cartoonist Adrian Raeside has a family connection. His grandfather and two great-uncles were on the Scott expedition, although they were in the party who remained at base camp and survived.

Raeside has since visited Antarctic and written his own book, Return to Antarctica.

Another member, Cecil Henry Meares, supplies another Victoria connection because he retired to live quietly in the city until his death in 1937.

Meares also has a personal history that reads like an adventure novel: officer in the British army, navy and naval air service. He fought in the Boer War, the First World War, and spied in China, Japan and Asia, and trekked the Himalayas.

Part of his heritage is still known in Victoria gardening circles. The Himalayan poppy was a flower he introduced to flower beds here in Victoria.

The exhibition is at the Royal B.C. Museum until Oct. 14.

• Anyone interested in learning more about the Race to the End of the Earth exhibit can hear about it from a man deeply involved.

Tim Willis, Royal B.C. Museum vice-president of visitor engagement and exhibitions, will present a lecture on the show on Sunday from 2 to 4 p.m.

The cost is $5 for the lecture at Newcombe Hall, and free to members of the Friends of the B.C. Archives.