The state has issued a permit allowing for archeological work at the site of a sunken Gold Rush-era ship in southeast Alaska.

A permit application was filed earlier this month by David Miller, an archeologist under contract with Kent, Washington-based Ocean Mar Inc. The Associated Press obtained documents related to the project, including a copy of the application and work proposal, through a public records request.

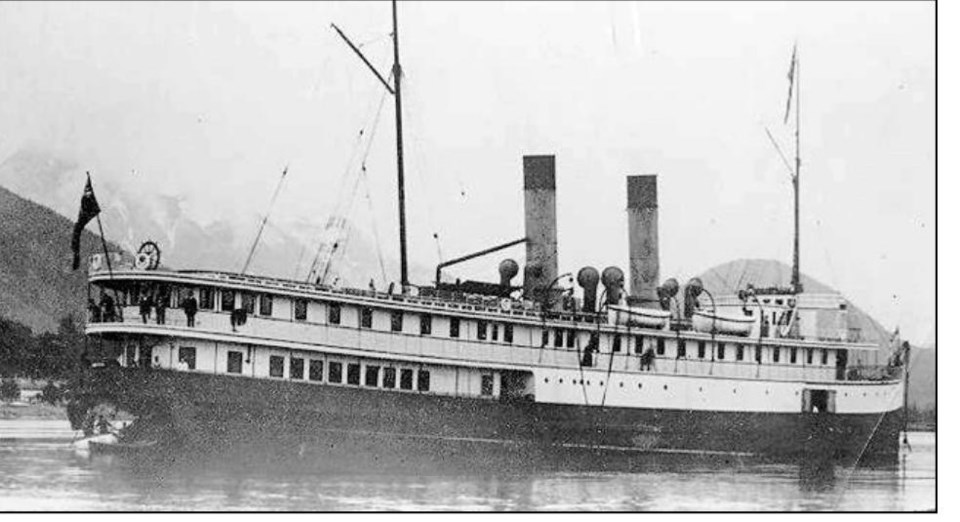

Ocean Mar fought for years for salvage rights to the luxury vessel, which was carrying about 180 people from Skagway, Alaska, to Vancouver when it sank in Stephens Passage on Aug. 15, 1901.

Forty people died, according to a court of inquiry report for the Canadian government. In April, a federal judge approved a recovery plan by Ocean Mar. Details remain under seal.

Miller's application lists August as the start of the proposed work, with no definitive completion date, and the Alaska State Museum as the proposed repository of collected items. The permit expires Dec. 31, but can be extended.

Dave McMahan, Alaska's state archeologist, said he wasn't aware of any other permits that might be needed for work to commence. An attorney for Ocean Mar did not return a message.

McMahan, in an Aug. 2 memo to colleagues, prior to the permit's issuance, said granting the permit would help ensure the state receives information from Miller's work that would, in part, contribute to its understanding of the crash and aid in the decision-making about what artifacts the state will keep.

Mystery has long surrounded the demise of the posh Islander, once thought unsinkable. Ocean Mar, in court documents, has said the story of the Islander hitting an iceberg in Lynn Canal appears to be false.

And what about any gold?

Ocean Mar, in a 2007 court filing, said research indicated at least six tons of gold bullion in wooden boxes was stored in a passenger cabin. But what was initially thought to be boxes of bullion during dives at the site that year turned out to be "glacial boulders having the same or similar size and shape of bullion boxes," according to another court filing. Subsequent surveys in the area indicated scattered bullion bars, according to court records, but it isn't clear, from information in the court file that has been made public, how much gold the company, reasonably, might expect to recover.

Parts of Kelly's proposal, released through the records request, are blacked out, including details on the importance of the site, the site's description and details of the investigation stages and overall project goals. The state said agencies may redact information that qualifies as a trade secret or would put an archeological or historic resource at risk.

It does say the project will consist of co-ordinated remote sensing, debris removal and "treasure and artifact recovery." Some of the debris is associated with a prior recovery attempt in the 1930s.

Much of the information collected by others over the last century "is to say the least, questionable, particularly regarding the contents of her cargo," Miller wrote. The goal "is to separate fact from fiction by determining if her now-almost-legendary cargo of gold exists."