Victoria’s Bill Noon thought it odd when the three Parks Canada archeologists beckoned him into his own quarters aboard the Coast Guard ship he commands.

“As captain, it’s really strange to have them pull you into your own cabin and close the door behind you.”

The trio had a secret: Two of them had just found one of the lost ships of the Franklin Expedition, intact on the Arctic ocean floor. After more than 160 years, one of the greatest mysteries in Canadian history was solved.

“We all cried, actually,” says Noon. “It was that overwhelming.”

Noon, 54, is back in Victoria, the home base of the Sir Wilfrid Laurier, the vessel at the heart of this month’s discovery. Four weeks later, he’s still almost shaking with excitement. Nothing in his 34-year Coast Guard career has come close to this.

“It’s every seaman’s dream,” he said Monday in the Maritime Museum of B.C., where plans of the Franklin Expedition’s two ships, HMS Terror and HMS Erebus, have just been affixed to a wall.

The Franklin tale is the stuff of legend. Led by explorer Sir John Franklin, the Arctic voyage left Greenhithe, England, in May 1845 with 129 men aboard. The ships were seen entering Baffin Island that August — then disappeared.

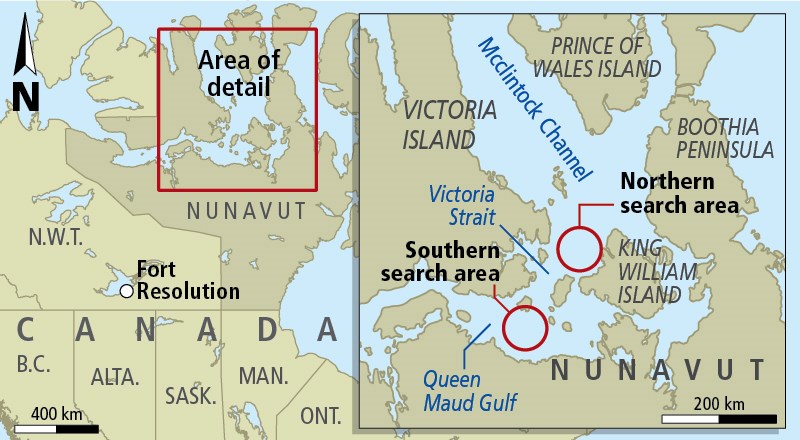

An insistent Lady Jane Franklin drove a series of searches that failed to find her husband’s vessels, though eventually the fate of the crew became known: after becoming stuck in the ice of Victoria Strait near King William Island in 1846, the men finally abandoned the ships in April 1848. They set out overland in a desperate attempt to reach the Hudson’s Bay Company settlement at Fort Resolution, 1,000 kilometres away. None survived. Indications are some resorted to cannibalism.

All this is well-documented. Less well-known is the Victoria connection to Arctic exploration in general and the Franklin hunt in particular.

Lady Franklin herself spent a month here in 1861. (Arriving after several months in the U.S., she was, according to travelling companion Sophia Cracroft, happy to be “once more among our own people only, after many months of residence with Americans.”)

It was also from Victoria that the Arctic exploration ship Karluk sailed in 1913 with a complement of 31 — including a seamstress and her two children — only to be crushed in the ice and sunk. The ghastly story of hardship and endurance included the deaths of 11 men before the remainder were rescued after many months.

The Canadian Coast Guard’s Laurier sets out from Victoria every summer, with the search for the Franklin ships being part of the itinerary each year since 2008.

This year’s search was part of a ramped-up effort, the Parks Canada-led endeavour also including players such as the Royal Canadian Navy, Royal Canadian Geographical Society, plus former BlackBerry boss Jim Balsillie’s Arctic Research Foundation, which contributed a converted trawler. The Laurier carried its crew of 27, a score of other search participants, plus Parks Canada’s small boat Investigator and two hydrographic research launches that could be sent ahead to map what were literally uncharted waters.

“We had to map a chart just to get there,” Noon says. “There’s absolutely no charting whatsover in these areas.”

The expedition was focused on two areas 100 nautical miles apart. The northern one was west of King William Island, where the Terror and the Erebus had been abandoned. The northwest coast of the island has been a treasure trove of Franklin clues, including skeletons and graves. “The beach is littered with buttons, toothbrushes, bones … It’s an archeologist’s dream,” says Noon.

The southern area was chosen largely because of local legend. “The Inuit have great oral history of one of the ships.”

The intent had been to focus on the northern zone this summer, but the return of the ice forced the flotilla south.

The first clue that they were in the right place came in early September when the Laurier’s helicopter flew out to place navigational aids on a small island. A couple of archeologists hopped on the chopper to see what they could find.

Noon was waiting on the Sir Wilfrid Laurier’s deck when one of the returning men, a Nunavut government archeologist, approached with an excited look. “He got off the helicopter and said ‘we found something really cool.’ ”

The “something” (it was actually pilot Andrew Stirling who made the discovery) was a piece of metal, stamped with the distinctive broad arrow that the British navy used to identify its property. Noon, who kept detailed drawings of the Franklin ships on his cabin wall, quickly identified it as a davit (though he says Parks Canada underwater archeologists came to the conclusion first). It had to be from one of the lost ships. It fit with Inuit history, too. “They were right all along,” Noon says.

The discovery refocused the Franklin search. “We knew it had to be really close.”

It was Parks Canada’s Ryan Harris and Jonathan Moore who, out on the Investigator, saw the sunken ship show up on side-scanning sonar, just 11 metres down. “Ryan said it was like winning the Stanley Cup. The second he saw it, he knew what it was.”

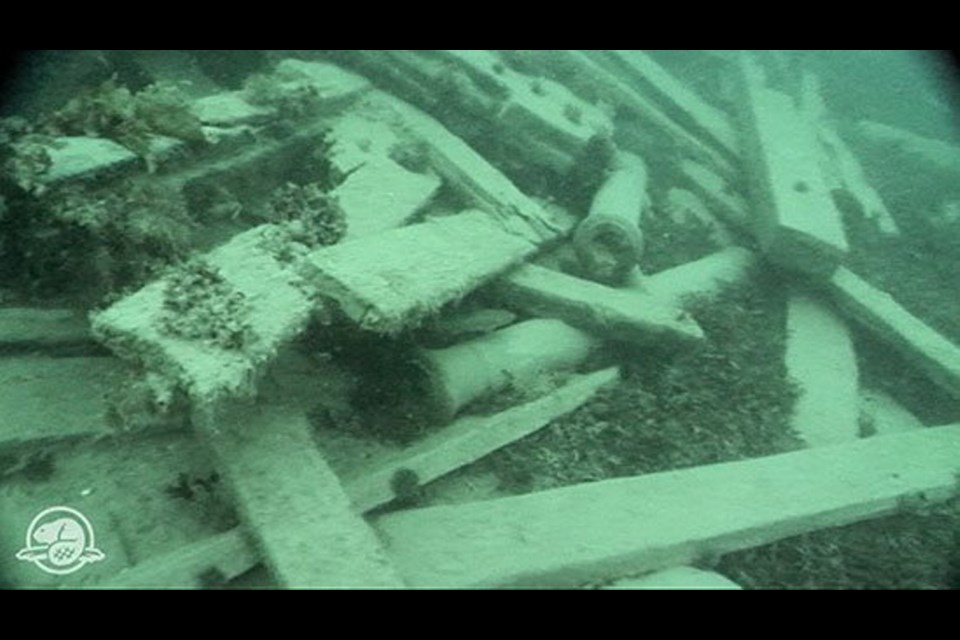

It wasn’t until they sent a remotely operated vehicle down to take pictures that they could confirm it, but what they saw was exciting. The vessel — they don’t yet know whether it’s the Terror or the identical Erebus — is sitting upright. Anchors have fallen straight off the sides. A pair of cannon are clearly visible. “The ship is so intact … the whole story could be inside this ship,” Noon says. “For an underwater archeologist, this is as good as it gets.”

The news was made public Sept. 7 by Prime Minister Stephen Harper, whose enthusiasm for the project led some Canadians to wrinkle their noses and grump about political exploitation and the resources dedicated to this one aspect of Canada’s history.

But a BBC commentator compared the discovery to that of King Tut’s tomb. And the New Yorker magazine explained its significance thus: “To translate it from Canadian into American terms, it is as if someone had found, in a single moment, the hull of the Titanic, the solution to the mystery of the lost colony at Roanoke, the original flag of ‘The Star-Spangled Banner,’ and the menu for the Donner Party’s last meal.”

As for Noon and the crew of the Sir Wilfrid Laurier, they’ll have to wait for another crack at the wreck. The Coast Guard ship, which left Victoria on July 4, has been chased out of the Arctic by bad weather. The Franklin search, which began Aug. 28, was just part of the ship’s summer; at one point the Laurier rescued 19 stranded Inuit hunters, including nine children.

It’s thrilling to have been part of history, though. Dozens of previous voyages had been dedicated to ending the mystery, notes Noon, who keeps maybe 20 books on the Franklin Expedition in his cabin.

“To be part of solving the riddle, it’s overwhelming.”