Two U.S. historians have shed new light on a little-known but powerful story from 19th-century Canada, when black settlers on Vancouver Island orchestrated the dramatic escape of a 12-year-old slave from his master in Washington territory, on the U.S. side of the border.

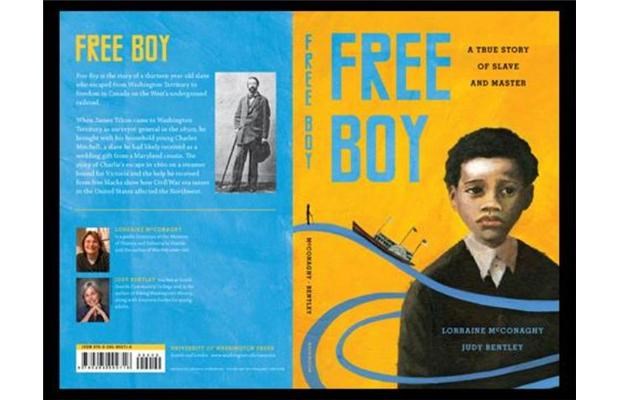

A rare example of the Underground Railroad operating on the Pacific frontier, the 1860 rescue of young Charles Mitchell by abolitionists in pre-Confederation Victoria — and the ensuing legal battle that resulted in a landmark victory for freedom — has itself been rescued from obscurity this month with the publication of Free Boy: A True Story of Slave and Master on Puget Sound.

At a time when the fate of escaped slaves was always uncertain — even in the abolitionist “promised land” of British North America, where U.S. bounty hunters sometimes roamed in search of runaways — the Mitchell case reinforced the rights of fugitive blacks and helped galvanize a newfound sense of citizenship within Vancouver Island’s fledgling African-Canadian community.

Free Boy co-author Lorraine McConaghy, public historian at Seattle’s Museum of History and Industry, said she first learned of the Mitchell story while searching for regional links to enhance a travelling exhibit on the Civil War that came to Washington state in 2008.

“I had come up through many levels of schooling here, always being told there was no Civil War story here,” she said.

But McConaghy’s research turned up a brief, 1860 article from a Seattle newspaper headlined “A Runaway Slave Case,” and her first thought was: “A fugitive slave, Underground Railroad — this is probably Ohio or Indiana or Ontario. But no, it was Victoria. And that was me stumbling on the Charles Mitchell-James Tilton story.”

The news brief, printed in the San Francisco Daily Evening Bulletin on Oct. 18, 1860, described how “a mulatto boy belonging to Gen. James Tilton, of Olympia, Puget Sound” had escaped to Victoria as a “stowaway” aboard the steamship Eliza Anderson.

The story indicated that certain “parties to his escape” in Victoria had alerted authorities with what was then the Colony of Vancouver Island to ensure the boy was not shipped back to continued enslavement in Olympia.

Tilton was Washington territory’s surveyor-general, a prominent figure in the pre-statehood era who had received the “gift” of a young slave boy from a relative in Maryland.

Those who helped arrange Charles’ escape were newly settled black residents of Victoria. They had been part of a group of some 600 immigrants who’d come north from San Francisco in 1858 during the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush.

Several of them had apparently made contact with Charles Mitchell weeks earlier in Washington territory and encouraged him to escape on a Victoria-bound cargo ship.

In Victoria, there was a brief legal standoff during which Charles was at risk of being sent back to the U.S. Tilton’s lawyers sought to secure “the immediate delivery of said negro Charles that he may be returned to his master,” but Vancouver Island justice officials ruled that the boy’s presence on British soil guaranteed his freedom.

The story of Mitchell’s escape is “not completely unknown – it was in the newspapers at the time – but it had been forgotten,” McConaghy told Postmedia News.

“And the reasons for forgetting it are interesting to probe,” she added, noting a “conscious disinclination to emphasize a story like this one” in the history of the U.S. Pacific Northwest.

But “people brought their convictions here with them, when they settled in the northwest,” she said. “That’s as true of Victoria as it is of Washington territory.”

Nevertheless, the dominant historical narrative in the state education system suggests that rather than transplanting the battle over slavery from back east, “people came west to get away from the war. They were busy planting orchards and panning for gold.”

McConaghy and her co-author, Judy Bentley, have told the Charles Mitchell saga in a new book aimed at young readers, so the story can spread among a new generation of U.S. citizens.

And Crawford Kilian, one of the few B.C. historians to have written about the Mitchell case, applauded the U.S. authors for shining a spotlight on an important and long-overlooked moment in Canadian history.

“Charles Mitchell’s story does deserve to be better known,” said Kilian, author of the 2008 book Go Do Some Great Thing: The Black Pioneers of British Columbia. “It shows two kinds of determination: Charles Mitchell’s determination to escape to freedom, and the Victoria black community’s determination to make him free.”

He said knowledge about the 19th-century black community in B.C. is limited to “what we learn in school — and until recently, that was very little.

McConaghy said there’s a sad footnote to the Charles Mitchell story. Another newspaper clipping — this one from an 1876 edition of Victoria’s British Colonist — describing the disappearance and apparent death of a “colored man named Charles Mitchell” and a “white man known as Bill” after their canoe, laden with shingles for delivery to an unknown destination, was found overturned near Sooke, B.C.

Charles Mitchell appears to have died before reaching the age of 30, but as a free man. The grim notice in the British Colonist said Mitchell left a wife and four children — “one of whom has been born since he left home,” the paper noted.

“This is an important story for educators,” said McConaghy, “because it’s an important story for kids — that you can remake your life, that you’re not stuck with your lot.”