When rain starts drenching the West Coast, timely warnings on whether to expect a run-of-the mill pineapple express or a Biblical-style deluge can make the difference between catastrophe or just a soggy mess.

“If we can predict it, it helps,” said U.S. research meteorologist Martin Ralph, who is giving a public lecture at the University of Victoria today.

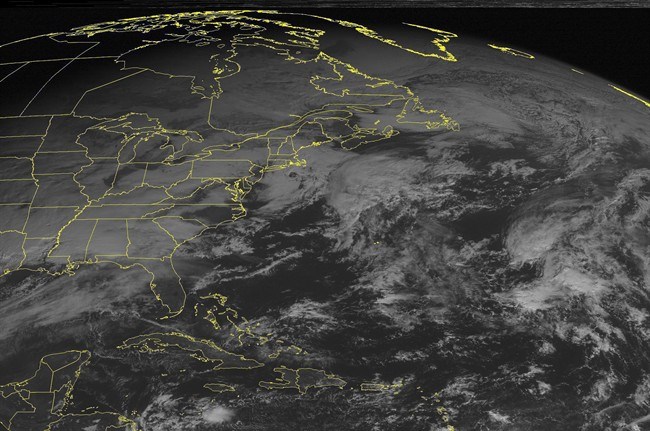

Ralph, whose research centres around atmospheric rivers — huge flows of water in the sky — hopes discovering more about the behaviour of these bands of water vapour will help forecasters predict where and when deluges will hit.

“Atmospheric rivers are a phenomenon we can predict a few days ahead and we’re working hard to zero in on exactly where it’s going to hit and how long it’s going to last and how strong it will be,” said Ralph, water cycle branch chief with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

“A few days ahead, we sometimes don’t know within 500 kilometres where it is going to hit. And even a day ahead of time we may be off by 150 to 200 kilometres,” he said. “Volumes of big rainfall events are under-predicted by 50 per cent, on average, on the U.S. West Coast.”

Many systems produced by atmospheric rivers — which can be 500 kilometres wide and thousands of kilometres long — are relatively benign, producing rain or snow or events such as Victoria’s recent pineapple express, heavy rain from Hawaii.

But others can create devastation. If an atmospheric river heavily laden with water vapour stalls in one area, especially if the watershed is already saturated, there will be problems, said Ralph, who predicts more extreme rainfall events will occur as the atmosphere warms.

A historical extreme rainstorm started on Christmas Eve in 1861 and pounded central California for 43 days, turning the state’s Central Valley into an inland sea, drowning cattle, killing thousands of people and bankrupting the state. California’s legislature had to move to San Francisco until Sacramento dried out six months later.

Studies of sediment deposits have shown such events occur in the area about every 200 years and another one is likely this century, Ralph said.

“The risk of an event like that is very real in our lifetime and, as we have learned through the tragedies of Katrina and Sandy, these rare events can be devastating,” he said.

That is why learning more about the atmospheric rivers and analyzing data from his agency’s 100 new weather stations is so important. The aim is to deliver accurate precipitation forecasts six to seven days before rain events happen, Ralph said.

That will not only improve flood preparedness and public safety, but also help with water resource planning as the climate changes, he said.

Free lecture

What: Storms, floods and atmospheric rivers

Where: Room D110, MacLaurin Building, UVic

When: Wednesday, 3-4 p.m.

Web: uvic.ca/ideafest