The number of homeless people who died in B.C. in 2014 was the highest on record in a single year — 46, a significant increase from 27 deaths the previous year.

Yet it doesn’t even take into account many of the largely preventable deaths, said Sean Cordon, executive director of Megaphone Magazine, which is sold by homeless people. “The true number is much higher,” he said.

A homeless person whose cold turns to pneumonia and who dies weeks later in hospital is not included in the count, Condon said. Nor do homeless deaths include people who were temporarily staying in a motel, squatting in empty buildings, living in correctional facilities or at residential detox centres.

Based on B.C. Coroners Service statistics, Megaphone’s report Still Dying on the Streets — Homeless Deaths in British Columbia, 2006-2014 has on its cover a photo of Anita Hauck, who suffocated last fall when she got stuck in a charity clothes bin in Pitt Meadows trying to reach garments for a homeless man who was feeling the cold.

This is the second consecutive year that the deaths of homeless people with access to shelter beds outstripped those of people with nowhere to sleep, Condon said.

In the past two years, 35 homeless people with shelter beds died, compared with 26 who were sleeping rough, he said.

“The shelter bed is often a mat on the floor and it is not safe and secure.”

Shelter beds have been increasing, and are an important tool, but “they are not the solution,” he said. “Social and affordable housing is needed to address this crisis.”

But homeless people need somewhere to turn in the short term. In Victoria, they have been flocking to a tent city on the Victoria courthouse lawn, which the province is attempting to dismantle.

The Housing Ministry has funded the 50-mat seasonal shelter at Metropolitan United Church for an extra month and asked the City of Victoria to consider leasing the 40-bed My Place shelter on Yates Street until Sept. 30 instead of April 30, as planned.

The 38 transitional units at Mount Edwards Court in Fairfield — purchased by the province for $3.6 million in February — quickly filled, and Choices, the former youth detention centre in View Royal, is almost full with 46 residents, 19 of them indoors and the rest camping on the site as renos continue.

From 2007 to 2013, Victoria had the highest per capita number of deaths of homeless people in B.C., at 33. That’s the official number. The University of Victoria Poverty Law Club documented 30 such deaths in just four months in 2012.

Of 325 homeless deaths in B.C. during that period, 80 were on the Island, including the Gulf Islands and Powell River.

Condon wants the coroners service to expand its definition of homelessness to ensure more accurate death figures and more funding to investigate them.

He’d like to see more tracking of the deaths of women in violent relationships to determine whether those women stayed with an abusive partner to keep a roof over their heads.

Barbara McClintock, spokeswoman for the coroners service, said making such determinations is not the mandate of the service.

“We’d get in a lot of trouble with the privacy commissioner if we started investigating every aspect of everybody’s life who died.”

If a woman dies in a car crash, a coroner can’t investigate whether she feared homelessness, McClintock said. People who die in hospitals in B.C. are not reportable under any circumstances — nor should they be, she added. “It’s a nice idea, but it’s not practical.”

Investigating the deaths of homeless people is “not essentially a question of resources, but of practicality — homelessness is a very fluid situation,” she said.

It’s hard for statistics to capture the situation of a formerly homeless person who is finally able to move into a bachelor suite, but, without supports, ends up dying of a drug overdose.

A 2011 report by then-B.C. Auditor John Doyle said that budget constraints threatened the coroners service. Funding slipped from $12.8 million in 2010-11 to $12.1 million in 2011-12 on top of cuts totalling $4.1 million in 2009 and 2010. Since then, the budget is holding steady at $12.3 million, McClintock said.

It’s to Condon’s “great credit” that he works to keep the important social issue of homelessness in front of decision makers, she added.

9 of 10 who died were men

Five things to know about the deaths of homeless people in B.C. from 2006-2014

• Almost 90 per cent were men

• More than 15 per cent were aboriginal people, who account for only five per cent of the B.C. population

• Of 325 deaths in B.C., almost 60 per cent were people ages 40 to 59, compared to an average lifespan of 76 in the general population of people born around the same time

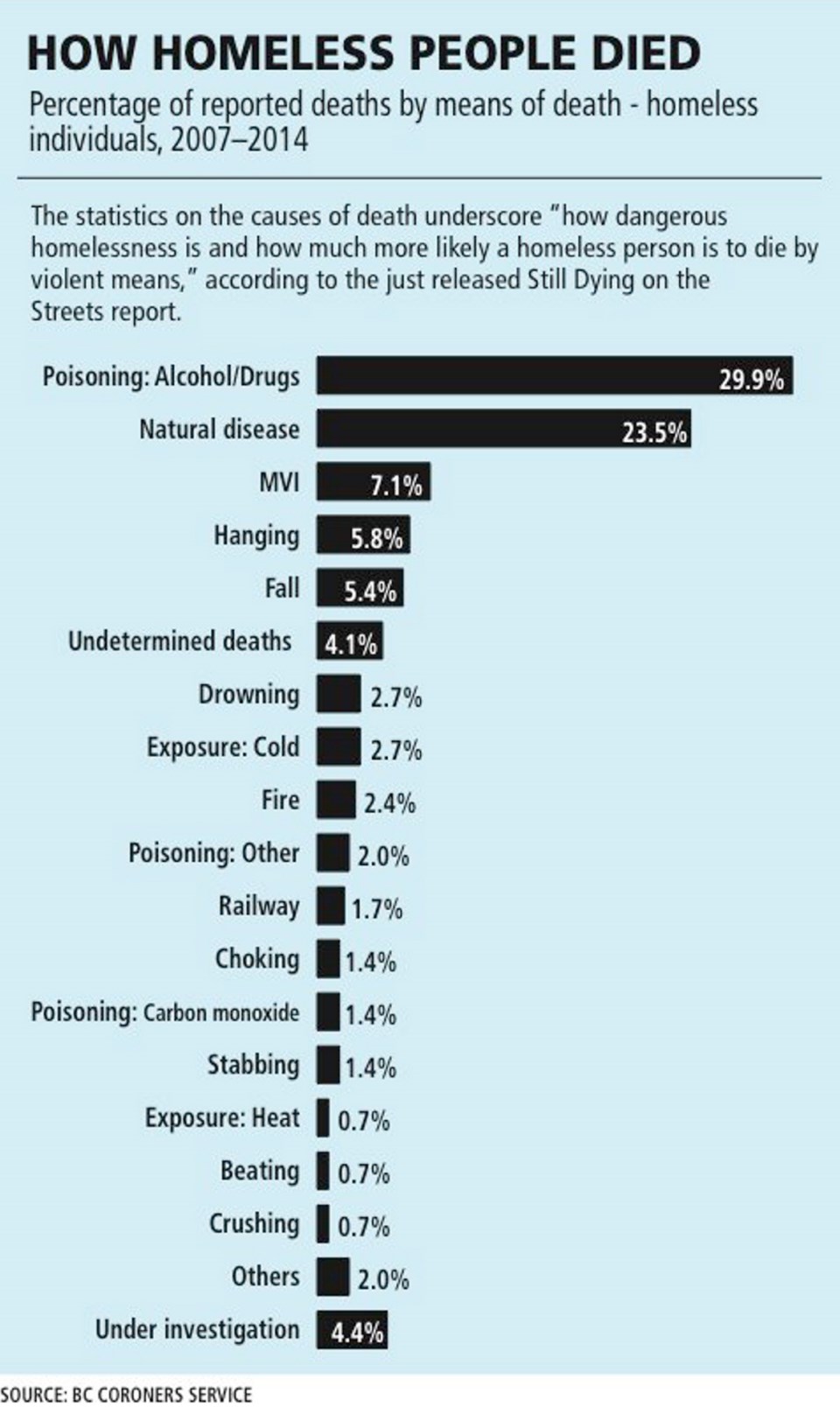

• The suicide rate per 100,000 population is 12.9 in homeless people, almost twice the 6.6 rate in the general population

• Only 26 per cent of homeless people die of natural causes compared with 73 per cent in the general population.