The B.C. government’s announcement Monday of $4.7 million to open an addictions recovery program in the fall at the former youth-custody centre in View Royal taints the credibility of the rezoning process, Mayor David Screech said, noting that resident input and council approval are still needed.

He said he’s personally in favour of a therapeutic-recovery community at the custody centre, at 94 Talcott Rd., but it needs to go through a proper process and needs the approval of View Royal council.

“And I feel like today’s announcement takes all credibility out of that public process and that’s a shame,” said Screech, following an announcement at Our Place Society that included Mental Health Minister Judy Darcy, Finance Minister Carole James and Island Health.

The therapeutic-recovery community, with space for 50 males, is to be run by the non-profit Our Place Society for people in a cycle of addiction, homelessness and incarceration.

The goal is for residents is to leave the program after a year or two, in control of their drug addictions, with a place to live, a job and all the life skills necessary to thrive in the wider community. The idea is that a community of peers heals the individual.

The opioid overdose crisis — the worst public health emergency in B.C. in decades — dictates that the government act with “urgency from ideas to action,” said Darcy. “Because we see the very real needs, the life and death needs, of British Columbians every day.”

Last year, more than 1,400 people died of illicit drug overdoses. The majority were men, people using drugs alone, using poisoned street drugs. One in ten were Indigenous people.

“There isn’t a single pathway to hope,” said Darcy, “so we have expand and have a wide range of treatment and recovery options.”

It will include Indigenous and non-Indigenous healing approaches.

It is hoped that the rezoning process will be successfully concluded by the end of June and that renovations will take place over the summer allowing the facility to open in the fall and begin accepting male clients in 2019-20.

The program will be free for those referred through the criminal justice system, Our Place Society or related social-support service providers, and assessed as ready for treatment and suitable for the program.

Counsellors, case managers, health-care and social workers will guide residents as they perform tasks to keep the community running, keep to a work schedule, learn job skills and gain confidence.

Residents in this community approach are expected to hold themselves and others accountable, learn to improve social skills and behaviours, and build positive relationships.

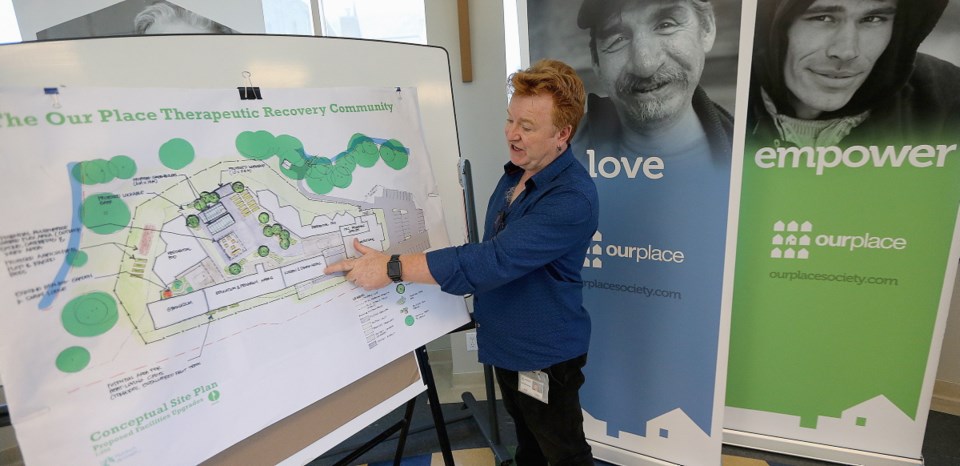

“We are grateful to the government of B.C. for supporting this life-changing program,” said Don Evans, executive director of Our Place.

Our Place Society is a non-profit organization that helps people in Greater Victoria connect with mental-health, addiction, housing and social services.

“This therapeutic recovery community … will save lives, it will transform lives, it will save the community money,” Evans said. Planning for the program started four years ago, he said.

Island Health is partnering with Our Place Society to support the clinical services.

Dr. Ramm Hering, an addictions specialist with Island Health, said addiction is a chronic brain illness. Long-term chronic illness needs to be met with long-term chronic treatment, he said.

In supporting the project, B.C. Housing will lease the property to Our Place for a nominal rate and provide a grant of about $310,000 for site renovations, and three years of property-tax costs.

The youth-custody centre has helped more than 100 people transition to permanent housing, according to the province.

Our Place has modelled its program on the San Patrignano Therapeutic Community in Italy, which reports a 72 per cent full-recovery rate for people who complete the program, Evans said.

About 50 to 70 per cent of residents successfully recover in similar programs, said Evans, and there is a minimal drop-out rate “because of peer support and peer pressure in the supportive environment.”