A couch. When the mystery ended Friday and Victoria’s Morgan Harker was revealed as the winner of that $25-million Lotto Max prize, these were his reported plans: A) take a Hawaiian vacation and B) replace a worn-out couch.

Now, a comfy couch is a wonderful thing (I once owned a chesterfield whose demise I mourned more than that of most blood relatives) but good Lord, when Buddy wins the big one, don’t you think his extravagance should stretch beyond a visit to Gordy Dodd?

Alas, this is typical of 99 per cent of Canadian lottery winners, whose plans are invariably, heartbreakingly the same: take a little trip, share a bit with family, invest prudently. When it comes to embracing rock star decadence, we tilt toward Anne Murray.

That’s a grave disappointment to the rest of us, who are left to live through the winner vicariously. Prudence? Please, we don’t want to hear about prudence unless she’s the hottie you shacked up with in Soho after flying to London for caviar and chips.

Which conjures memories of Vinnie Parker.

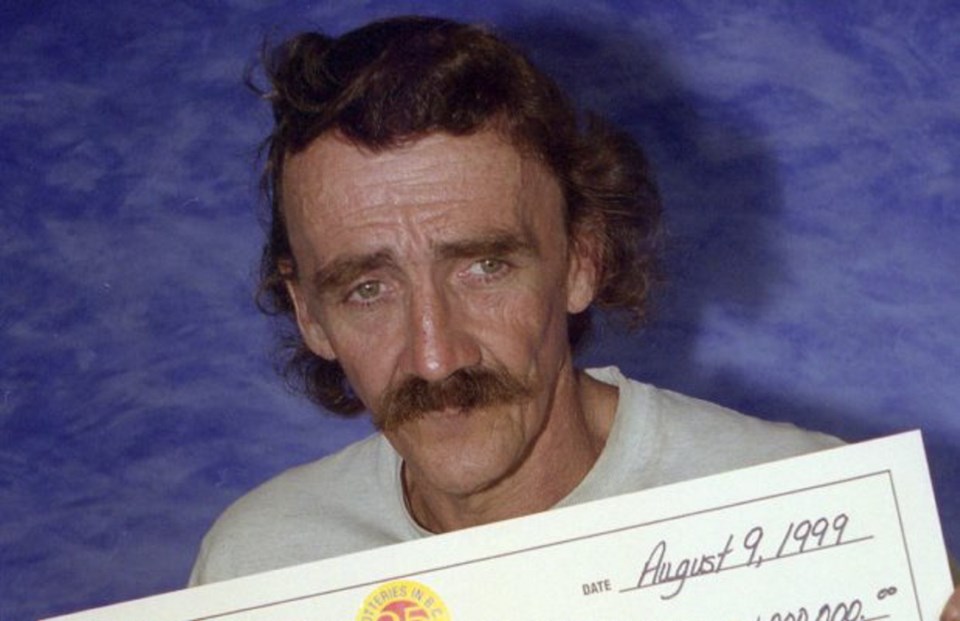

Parker was a logger from Zeballos (pop. 125) about 40 kilometres down an unpaved road off the Island Highway a couple of hours north of Campbell River. He was 51, living in an 18-foot travel trailer, when he won $1 million on the 6/49 in 1999.

Reluctantly dragged in front of the media in Victoria — it was a condition of getting the cheque — he became instantly, if fleetingly, famous when he outlined his plans for the money: “I’m going to blow it.”

He was going to buy some muscle cars, he said. He was going to build his own RV park so that he and his friends could party without being hassled like they were in the municipally owned one. (“Just to piss the mayor off.”) He was going to get his dog laid.

“If there’s anything worse than me having an attitude, it’s me having the same attitude and having money,” he told the TC’s Carla Wilson, then fled Victoria as though it were on fire, returning to the splendid isolation of Zeballos, an independent man’s paradise, as fast as he could. “Let me out of here. I don’t like the hassle of a city.”

He proved a man of his word.

“He said he was going to spend it all in six months, and he did,” his friend Rose Osmond said Saturday.

Parker bought a ’65 Barracuda and some other vehicles, purchased a house, built that RV park for his logging pals. (Sorry, I didn’t ask about the dog, a half-wolf named Sitka.)

He also got some mini-quads for the town’s kids to ride, and built a great, big motorcycle track for the bigger boys to play on. He sponsored four motocross competitors, including Osmond’s son. When people needed money, Parker had it, at least for a little while.

“Vinnie was just a great guy,” Osmond says. He was the neighbour with the chainsaw when you needed a tree dropped, the one who volunteered to bang the boards together when the village put in a couple of nature trails.

He kept logging, too, but when he died at age 63, two years ago this week, Parker was not a wealthy man.

He was, however, remembered fondly by every Vancouver Islander whose retirement plans are predicated on saying yes to the Extra. If you win the lottery, it is their money you are spending, and therefore your moral obligation to go a wee bit nuts on their behalf. Lottery winnings should come with the requirement that a certain percentage must be blown within a year. (Echoes of George Best: “I spent 90 per cent of my money on women, drink and fast cars. The rest, I wasted.”)

There are limits: You don’t want to end up like Michael Carroll, Britain’s famous Lotto Lout, whose £9.7-million jackpot at age 19 in 2002 shone a spotlight on a high-profile life of low-level crime and substance abuse, and who by this summer was broke, forced to take a £200-a-week job in a biscuit factory. But neither do you want to disappoint the rest of us by slipping into the Big Sleep with unfulfilled dreams.

“I did what I felt like doing,” Parker once grumbled after most of the money was gone. “I don’t know why people find it so [bleeping] amazing.”

Here’s why: In doing what he wanted, he wasn’t just living his own fantasy life. He was living ours.