As you curse and crawl down the Trans-Canada in this summer of Peak Malahat, spare a thought for Major James MacFarlane.

As you curse and crawl down the Trans-Canada in this summer of Peak Malahat, spare a thought for Major James MacFarlane.

For it was MacFarlane — mule-headed, hard-drinking, charming, considered barmy by friend and foe alike — who almost single-handedly cajoled and browbeat the government into building a road over the Malahat just over a century ago.

He also surveyed the route himself after being told it couldn’t be done.

It’s a tale that has been put together in a documentary by the Mill Bay/Malahat Historical Society, one that echoes in the present.

“What struck me is things haven’t changed at all,” says society president Maureen Alexander. There’s still really only one road connecting Victoria with up-Island. Government still cites the expense, the impossibility, of an alternative.

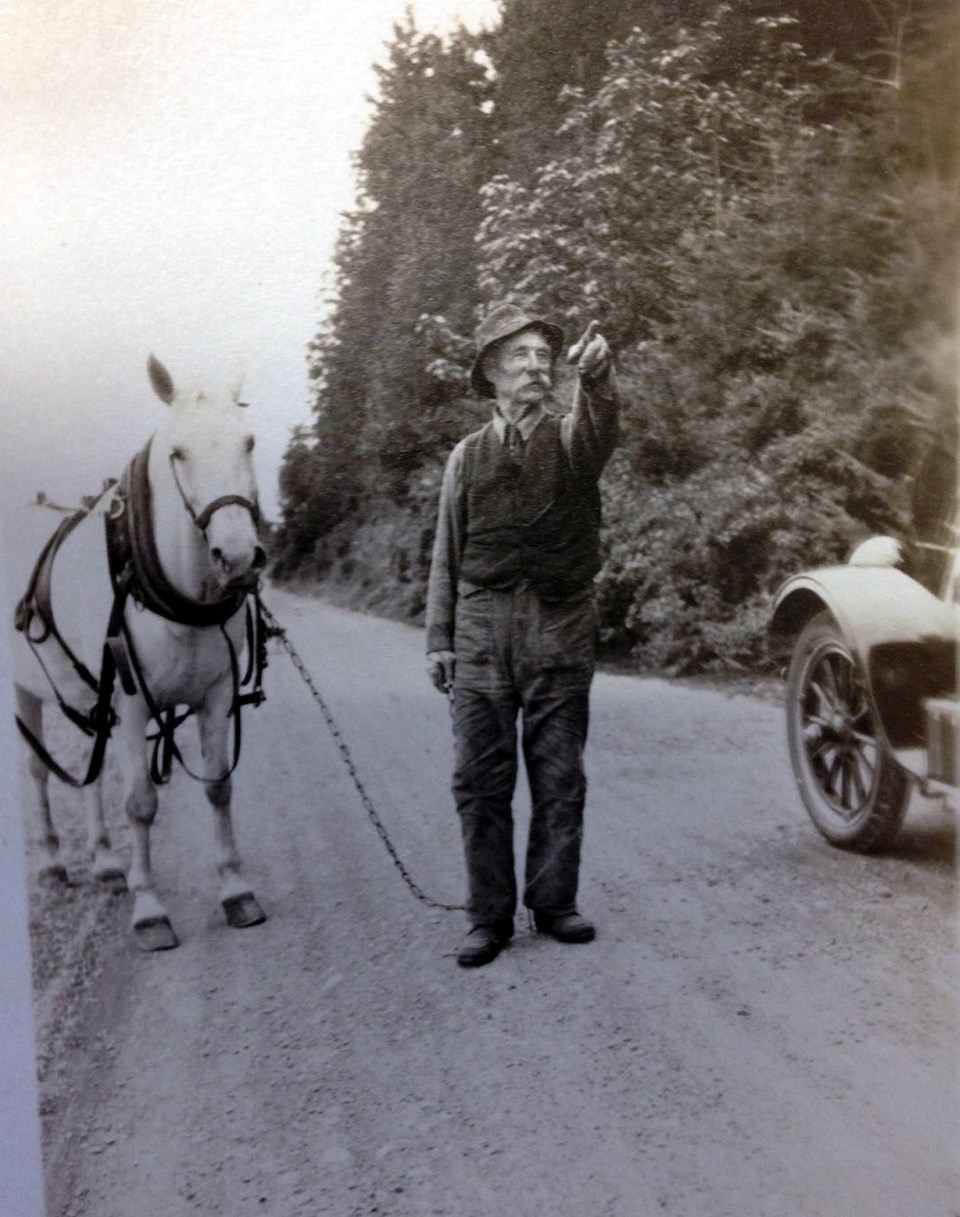

It was Alexander who first had the idea to make One Man’s Dream: The History of the Malahat Highway. The production, a community effort, blends archival material with re-enactments by actors, principally retired drama teacher Roger Carr, who looks like he had a lot of fun playing MacFarlane.

Who wouldn’t? The man was a character, a rogue, a rascal.

Born in Dublin, educated at Trinity College, MacFarlane served in the British Army in India before, just shy of age 60, buying a farm in the Mill Bay area in 1903.

He ate oatmeal each morning, reasoning that what was good for his horse would be good for him, too. He claimed to drink a bottle of Burke’s Irish Whiskey every day, too, planting the empties upside down along his driveway. It was a very long driveway.

Even his family found him challenging. If the last of his three marriages endured, it might be because his wife lived in a house on the Mill Bay waterfront while he lived in a cabin up the hill.

But he had the gift of the gab, was a first-class bullshooter (literally: He once killed a neighbour’s bull when it trespassed on his land, though when the case went to court the judge — with whom he had been known to tip a glass — declared MacFarlane had been justified in taking out El Toro). And he was tenacious.

Mill Bay was well-established by 1903, though it might have been Mars as far as Victoria was concerned. Reaching the capital meant nine hours by steamer from Nanaimo, a weekly sloop from Cowichan Bay, or a rowboat to the Saanich Peninsula.

An almost impassable route called the Goldstream Trail, really just a couple of wagon wheel ruts, ran 80 kilometres from Victoria to Goldstream, out to Sooke, around Shawnigan Lake, then on to Cobble Hill and Cowichan Bay. It was a three-day slog.

Pressing the government for an alternative, MacFarlane was told that more than 40 years of work by surveyors and engineers had shown there was no workable route. And why build a road when there was a railway?

Undeterred, MacFarlane, whose cavalry and artillery experience had taught him a bit about surveying, said he would mark a line himself. He spent three years bashing through the bush along the inlet until he had a route.

Government still balked, but MacFarlane wouldn’t let up. He set off to Victoria armed with a resolution of the Mill Bay Farmers Institute (OK, only three people showed up at the meeting, and he was jeered by his neighbours when he boarded the train at Cobble Hill) and won the support of the boards of trade and tourism.

He kept on pushing until Frank Verdier, a much-respected timber cruiser whose own role in the Malahat story should not be downplayed, was asked to check MacFarlane’s route. Verdier, bucking political pressure, confirmed MacFarlane’s findings, putting more pressure on the government, which eventually relented.

Construction was a challenge (the company that first won the road-building contract bailed) but when the road opened in 1911 it was acclaimed as a scenic wonder (albeit one featuring a cliff-hugging single lane with few railings). The politicians didn’t forget how much of a pain in the butt MacFarlane had been, though, and he wasn’t invited to the official opening. However, a bottle of Burke’s to each member of the work crew ensured that it was MacFarlane’s car, not that of a sputtering Premier Richard McBride, that drove through the ribbon.

It’s a good story, one that Alexander and friends are happy to share with community groups and others keen on learning a bit of local history (email her at [email protected]).

At the core of the tale is one audacious, unrelenting, unlikely man. “It was that persistence and obstinance,” says Alexander, “that got the road built.”