Here’s a question: Why name a federal research ship after a foreigner synonymous with disaster when you could celebrate Canadian achievement instead?

Here’s a question: Why name a federal research ship after a foreigner synonymous with disaster when you could celebrate Canadian achievement instead?

Which, in a nutshell, is what critics are asking as Canada prepares to launch the Sir John Franklin next winter.

The ship, a replacement for the Nanaimo-based W.E. Ricker, is the first of three offshore fisheries research vessels being built for the Canadian Coast Guard by Seaspan in North Vancouver.

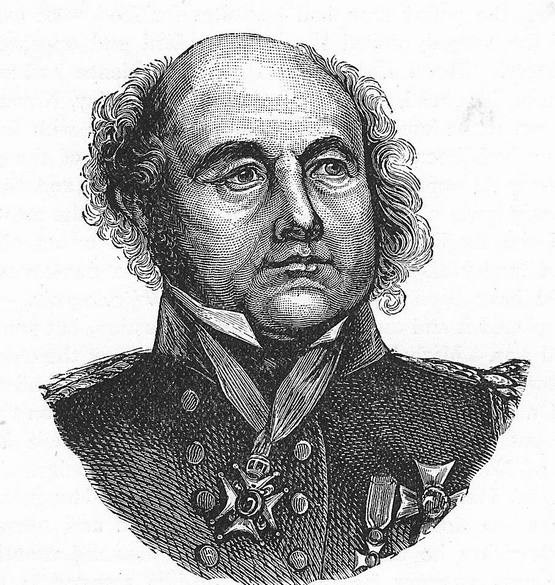

As construction began in June 2015, Ottawa announced the 63-metre vessel would be named after Franklin, the explorer who famously (or infamously) disappeared into the Arctic with both of his ships and all 128 of his men after sailing from England in 1845.

The ships’ whereabouts remained one of the world’s great mysteries despite dozens of attempts to find them over the years. Franklin’s wife, the indomitable Lady Jane Franklin, drove a series of searches that failed to locate her husband (she actually spent a month in Victoria in 1861), but that did have the effect of gradually filling in the map of the north, cementing Britain’s — and subsequently Canada’s — territorial claims.

Eventually, the fate of the sailors emerged: After becoming stuck in the ice of Victoria Strait in 1846, they set out overland in April 1848 in a desperate attempt to reach Fort Resolution, 1,000 kilometres away. None survived. Although remains of crew members were found (indications are some resorted to cannibalism) the location of the ships was unknown — until a couple of years ago.

The Franklin mystery was big news in 2015, given that the expedition’s flagship, HMS Erebus, had just been found intact on the ocean floor the previous September. (The Victoria-based coast guard ship Sir Wilfrid Laurier played a central role in the discovery; in March 2015, two dozen members of the crew were awarded medals by Sen. Nancy Greene Raine at Sidney’s Institute of Ocean Sciences.) The second sunken ship, HMS Terror, was found last year.

If the romance of it all made politicians keen to slap the Franklin name on the new research ship in 2015, some historians and scientists are balking today. Who wants to serve on a vessel whose name conjures up an image of nautical disaster? That would be like sailing on a nuclear submarine named USS Chernobyl. Why not honour a successful Canadian instead?

“It’s a complete puzzle to me,” says Robie Macdonald. “It’s a sad thing that they have taken an opportunity to do something good and turned it into a negative.”

Macdonald is an emeritus research scientist with the Department of Fisheries and Oceans at the IOS. One of the world’s leading marine geochemists, in December he was awarded the Polar Medal for his work in the Arctic. He’s not the only researcher to complain about the Franklin choice, but he’s one of the few to do so publicly. (Scientists might no longer be burned at the stake now that Stephen Harper is gone, but they’re still not volunteering to take potshots at the government.)

Why not give the ship an indigenous name, Macdonald asks. Or why not honour one of the many deserving women in ocean research? (Coast guard ship names tilt to the masculine.) “There are a lot of people they could have named it after.”

In fact, last summer, a senior manager sent DFO scientists an email asking for alternatives to the Franklin name. Of the 15 suggestions, five possibilities were forwarded to the vessel-naming committee: Helen Irene Battle, the co-founder of the Canadian Society of Zoologists and the first woman in Canada to earn a PhD in marine biology; Michael Bigg of Nanaimo, the father of modern whale research; Bob Kabata, a Polish Second World War hero who went on to win the Order of Canada as a parasitologist; Daniel Ware, an award-winning fisheries biologist at Nanaimo’s Pacific Biological Station; and the station’s Edith Berkeley, a pioneer of marine biology.

But the coast guard believes the discussion was about names for the other research ships being built, not the Franklin, a choice that already fit the naming criteria: former Canadian scientists or explorers of Canada. (There actually used to be a coast guard icebreaker called the Franklin that was renamed the Amundsen, after the Norwegian polar explorer, when the ship became an Arctic research vessel.) There are no plans to revisit the Franklin decision.

That doesn’t sit well with Macdonald.

“I think it was a bad choice,” he said. “We have people to celebrate in this country. Why not celebrate them?”