Today, soldiers of the Canadian Scottish will make the short trek from the Courtenay cenotaph to the nearby — but almost forgotten — grave of Roger Schjelderup.

Today, soldiers of the Canadian Scottish will make the short trek from the Courtenay cenotaph to the nearby — but almost forgotten — grave of Roger Schjelderup.

Two days later and 7,600 kilometres away, Schjelderup’s widow and son will lay a wreath in his memory near Buckingham Palace.

And sometime next summer, one or more of the fitter, younger members of the family will spend three days hiking high up the spine of Vancouver Island to the lake that bears his name. Maybe they’ll pour a little more scotch in the lake, toast his name beside the memorial marker that isn’t supposed to be there.

Schjelderup was remarkable. In 1937 at age 15 he climbed the Island’s highest mountain, the 2,200-metre Golden Hinde, just after a team of surveyors made the first recorded ascent of the peak. Eight years later, he was among the most highly decorated Canadians of the Second World War.

Like many Islanders, Schjelderup enlisted in the Canadian Scottish Regiment. By June 1944, the young lieutenant, leading a platoon of C company, was among the first to leave footprints on Juno Beach on D-Day.

They got chewed up as they advanced inland. By nightfall no platoon had been hit harder than Schjelderup’s, wrote Reg Roy in his regimental history Ready for the Fray. ‘‘He had come ashore with 45 men under his command. At the end of the day when he, himself, was ordered back to have his wounds dressed, there were only 19 men left.” Schjelderup’s actions earned him the Military Cross.

By October he was back in action on the Holland-Belgium border, where he led a company that stubbornly held off a massive counterattack long enough for other troops to get in position to prevent the Germans from recrossing the Leopold Canal. But Schjelderup, wounded by a grenade and with his headquarters on fire, was captured.

He wasn’t a prisoner long. Two weeks later, using a penknife that a Sergeant Gri had managed to hide, the Canadians cut their way out of the boxcar in which they were held. A farmer hooked them up with the Dutch Resistance, whom the Canadians joined in raiding German targets.

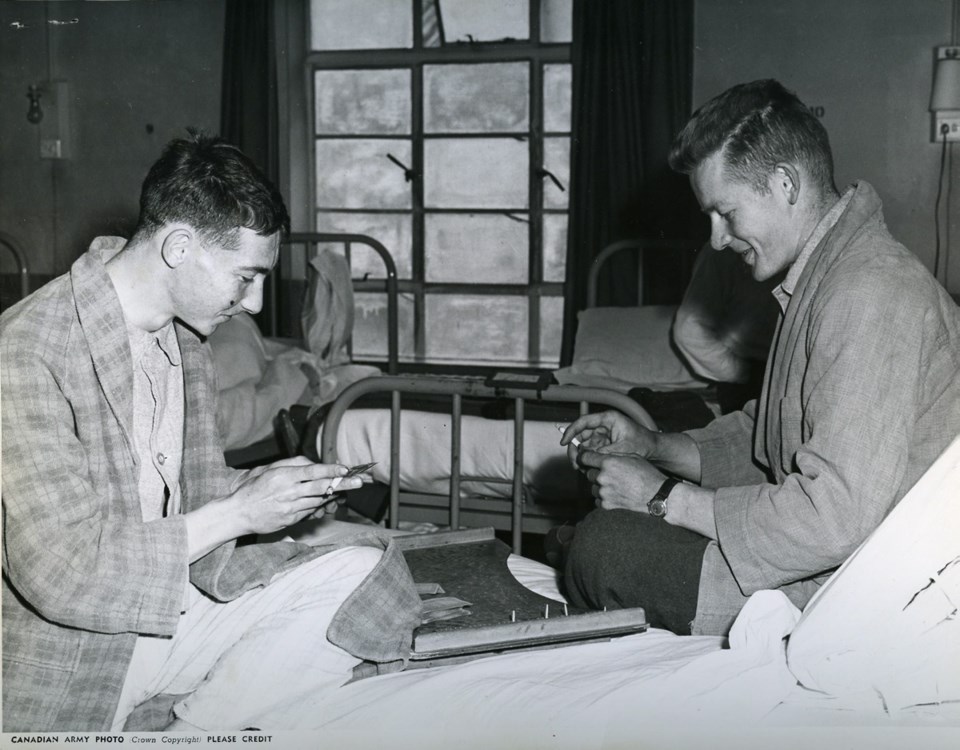

It took Schjelderup several weeks to recover from his wounds and pneumonia, but in late December he was in a small group that set out for Allied lines. It was harrowing journey: shot at by the enemy, slowed by snow, crossing canals covered by ice not quite thick enough to bear a man. “A number of times the group stumbled over trip wires leading to mines and booby traps which, with their mechanism frozen solid, did not go off,” wrote Roy.

Finally, on Jan. 5, 1945, the ragged band was taken in by the forward troops of a British unit, who fed them tea laced with rum.

Schjelderup was awarded the Distinguished Service Order (a rare honour for a junior officer) for the Leopold Canal and a bar to his Military Cross for his actions later.

That’s a very stripped-down version of a dramatic story, the kind of tale that would have been made into a Hollywood movie were Schjelderup from another country.

Instead, few of us even know his name. After Schjelderup’s death in 1974, it was left to his childhood friend and fellow outdoor enthusiast Ruth Masters — who is still a much-respected Vancouver Island environmentalist — to drive the campaign to have a Strathcona Park lake near the Golden Hinde named in his memory. Even then, the parks branch balked at allowing a memorial cairn beside Schjelderup Lake.

Magically, a plaque appeared there in 2002. Family members gave it a proper blessing: “We poured half a bottle of Johnny Walker into the lake,” says Schjelderup’s son Eric. Every year, one or more Schjelderups make the arduous hike in to pay their respects. It’s a three-day grind to get there, but Eric says it’s worth it. “It’s an absolutely gorgeous spot, even though it’s really remote. You can hear a pin drop up there.”

Eric says this while on the phone from Herstmonceaux, Sussex, where his mother lives. She stayed in England after her husband died there while serving as Canada’s senior military liaison officer. On Sunday — the British hold Remembrance Day on the Sunday closest to Nov. 11 — mother and son, at the behest of Canada’s high commission, will lay a wreath in memory of Schjelderup and his platoon at the Canadian war memorial in Green Park, close to Buckingham Palace.

It feels good to keep his father’s memory alive, Eric says. He notes that even the Canadian Scottish had, until recently, lost track of the whereabouts of his father’s grave (it’s in a churchyard a short walk from the Courtenay cenotaph).

But that’s what happens as the years pass, as personal connections disappear. Only a handful of Schjelderup’s Canadian Scottish contemporaries remain.

Similarly, the great majority of the million Canadians who served in uniform in the Second World War are gone, remembered as individuals mostly by old comrades and children who are themselves now grey-haired. If the memory of someone as celebrated as Roger Schjelderup can fade, how about those who live on only in our hearts?