Ruth Masters called up one day to propose an April Fool’s story for the newspaper.

“Report that the Comox Glacier is being carved up and sold to the Middle East for drinking water,” she said. “Quote me as being outraged about it. That will make people think the story is real.”

Well, yes, they probably would have believed it, for if anyone was passionate about the glacier and all the other natural wonders of Vancouver Island, it was Masters.

“She has been a crusader for a variety of causes, and belongs to 23 animal rights groups, 27 environmental causes, and about 40 peace and women’s rights groups,” reads her entry in beyondnootka.com (a good place to learn about the mountains of Vancouver Island and those who roam them).

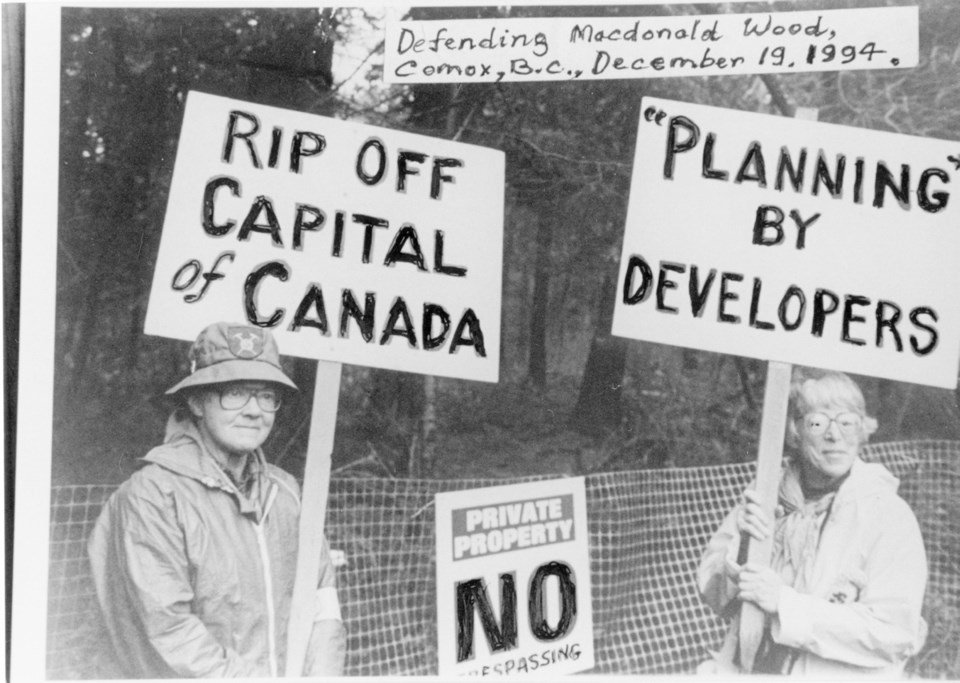

The bio goes on to rhyme off her eco-battles, including the three-month blockade against mining in Strathcona Park in 1988, the logging blockades of the early 1990s — Lower Tsitika Valley, Carmanah, Walbran, Clayoquot Sound — and her 1995 arrest for disrupting a big-game hunt near Port McNeill (“As a bear was about to be shot, Masters threw rocks at the animal and blew her rescue whistle”).

Masters kept rocking the boat, or at least pounding out letters on her typewriter, right up to her Nov. 7 death at age 97 in the Comox Valley, where she was born and raised and revered.

That last bit was telling. Eco-activists are often polarizing figures (Raging Grannies sometimes inspire the same curled-lip reflex as street mimes), but Masters’ motivation was so pure, her sense of place so profound, her commitment to community so strong and her willingness to sacrifice for what she believed in so evident, that it was hard to deny her respect.

Masters, who once donated 18 acres of her Puntledge River property to be preserved as a greenway and wildlife corridor, was so well-regarded that she was named the Comox Valley’s Citizen of the Year not once, but twice.

“She loved the Comox Valley. She never wanted to move away from here,” says Lindsay Elms, the author of Beyond Nootka.

Born in Comox in 1920, Masters made her first trip into the mountains at age 13, and first climbed the Comox Glacier at 18. (She was 71 when she ascended it for a sixth and final time.) She was one of the first members of the Comox District Mountaineering Club.

Having spent much of the Second World War in uniform in England with the Royal Canadian Air Force, she later campaigned to have lakes and mountains named in memory of the valley’s war dead. In fact, as a keen student of local history, she drove the naming of some 50 geographical features.

She would often hike in to those remote locations to install commemorative plaques, paid for out of her own pocket, on cairns that she and others would build. Victoria’s Marilyn Misner, who hiked, birded and maintained Strathcona park trails with Masters, recalls tromping in to build a cairn at Century Sam Lake, named after the fictitious prospector made famous by Courtenay’s Sid Williams. The expedition earned Misner one of Masters’ coveted Hero Spoons, awarded to those who helped the community. (Note that donations are being accepted for the annual Ruth Masters Hero Spoon Legacy Award, given to a North Island College environmental studies student.)

“Things were just a joy for Ruth,” Misner says. “She would say: ‘There’s nothing I can’t do.’ ” Misner says a lawyer Masters worked for as a legal secretary often said half the people in his office were there in relation to one of Masters’ causes.

Local historian Judy Hagen, who served with Masters on the museum board, remembers her friend as a woman of action, whether that meant recycling newspapers and tin cans before recycling was a thing, or protecting wildlife. Masters kept a rug in the back of her truck to wrap up injured or dead animals found on the road, and once headed off to the west coast of the Island to clean birds caught up in an oil spill. (It was after the latter episode that she persuaded Hagen, a Brownie leader, to have her charges collect old toothbrushes as bird-cleaning tools.)

Masters was kind to people, too. Up until the months before her death, she was still getting driven to hospital to play her harmonica for the bedridden. Hagen recalls her opening her home (and its shower) to a father and three children living in a travel trailer. Those she treated well didn’t always reciprocate, but this one did: The dad was one of those who nominated Masters citizen of the year.

She wasn’t one for silos, which explained much of her appeal: NDP-leaning Masters and Hagen’s husband Stan, a Socred and Liberal cabinet minister, liked and respected one another, which confounded those who were more partisan than Masters — but not those who knew her well. Stan even won a Hero Spoon for protecting Strathcona Park. “If she liked you, she liked you,” Judy says. And people liked her back.

They’ll gather to remember Masters at the Florence Filberg Centre in Courtenay 1-4:30 p.m. this Sunday.