B.C.’s overdose crisis appears to be worsening, sparking fears that drugs are becoming increasingly toxic and unpredictable, chief coroner Lisa Lapointe said Monday.

More than four people a day died on average in November for a total of 128 deaths, the highest number of illicit drug overdoses for a single month in recent memory.

With up to 13 people dying from overdoses in one day last week, the crisis shows no signs of abating.

“December is looking like a very bad month,” Lapointe said Monday in releasing the latest statistics.

“We are quite fearful that the drug supply is increasingly toxic, it’s increasingly unpredictable and it’s very, very difficult to manage those who overdose. And for those who are attempting to use drugs safely, it’s almost impossible.”

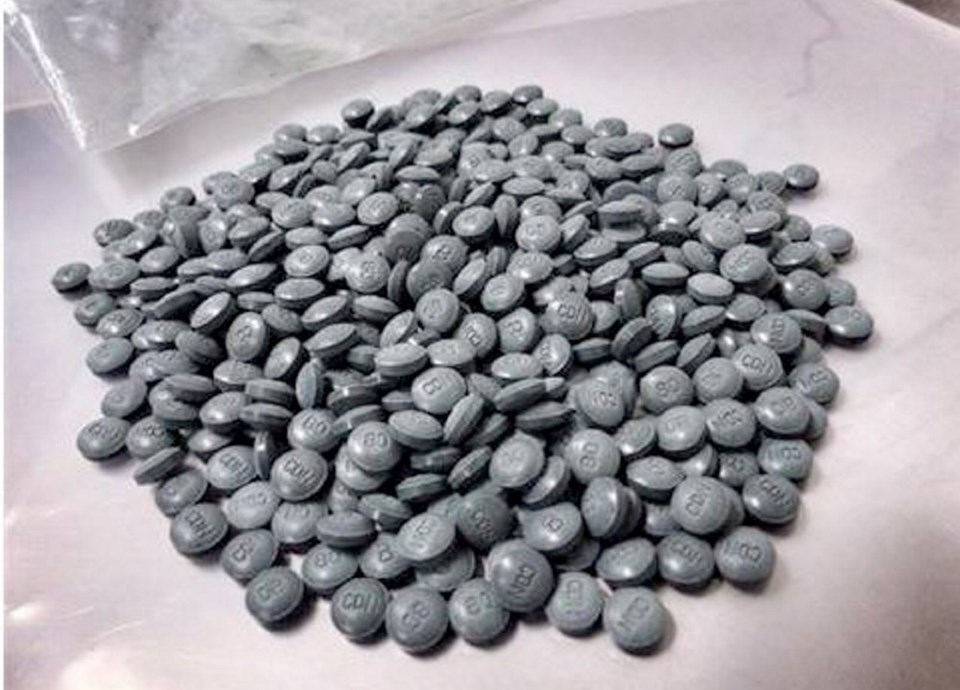

Lapointe said the rising number of deaths could be due to a more potent form of fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that has been linked to more than 60 per cent of all illicit drug deaths from Jan. 1 to Oct. 31.

“Or we may be facing the terrifying possibility of carfentanil being introduced broadly into the illicit drug stream,” Lapointe said, referring to an analog of fentanyl that is considered extremely toxic.

Carfentanil is about 10,000 times more potent than morphine — and up to 100 times more potent than fentanyl — and should never be prescribed for humans. It is used to tranquilize elephants and bears.

Lapointe urged people to only use drugs in the presence of someone who can call 911 or administer naloxone to reverse an overdose.

“As much as you may think you are taking a lesser dose or a safer dose and you may have your naloxone kit nearby to save yourself, you are at risk,” she said. “And we are seeing people die with a naloxone kit opened beside them, but they haven’t even had time to use it.

“The message has to be: You must go somewhere where somebody is able to give you immediate medical assistance.”

Provincial health officer Dr. Perry Kendall, who co-chairs a task force on overdose response, said the fact that increasing amounts of naloxone are being needed to reverse overdoses suggests the presence of more toxic analogs or possibly carfentanil. “I assure you that we are working at all levels to seek to put an end to these tragedies and to ease the pain that accompanies them.”

He said the evidence is clear that the first line of treatment for people taking opioids should be offering opioid replacement therapy using methadone or suboxone, and that the province needs a “continuum” of services rather than simply adding more treatment beds.

“Beds are a part of the solution,” he said. “But it’s what happens in those beds, it’s what happens before the beds and, critically, it’s what happens when they’re discharged from the beds and the community supports that you have. ”

Kendall said there has been a spike in people seeking help to get off drugs, and that those people don’t always get assistance when they ask for it.

Sue Hammell, the NDP’s spokesperson on addictions, agreed with Kendall about the need for a continuum of services. “I just feel that we have done a little on the treatment side, but too little and it’s too late for a lot of people,” she said. “And I think that is shocking. This crisis has been known; we hit the button on the crisis in April and it’s December and it’s still completely out of control.”

The November deaths raised the total illicit drug overdoses for the year to 755, a more than 70 per cent increase over the same period in 2015.

Greater Victoria continues to be hard hit, recording 60 overdose deaths so far this year, trailing only Vancouver at 164 and Surrey at 92. Nanaimo has had 25 deaths.

Vancouver Island Health Authority has the highest drug overdose rate among health regions with 19.7 deaths per 100,000 people from January to November — a 153 per cent increase over last year.

Dr. Richard Stanwick, chief medical health officer for Vancouver Island, said part of the problem on the Island is that the deaths are spread across urban areas rather than concentrated in a single area such as Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. “We don’t have core areas which we can deploy to and know that we’re going to have a specific impact,” he said.

A supervised consumption site would help, Stanwick said. “But it’s also that there’s a good portion of the population that, because of the stigma associated with addiction, hide their addiction, and those are the individuals that we also know are dying.”

Canada’s Health Minister Jane Philpott said in an interview that she was disturbed by the latest overdose numbers from B.C.

“I think we have seen the numbers continue to grow across the country but particularly in British Columbia and it’s frankly heartbreaking to think of these primarily young people whose lives have been cut short.”

Philpott said the federal government will work “very determinedly” to pass the Controlled Drug and Substances Act, which was announced last week to simplify the process of establishing supervised consumption sites. The changes could see two drug consumption sites operating in Victoria early in the new year.

But Philpott said the crisis requires a broader response. “We need plans for prevention and treatment and harm reduction and to look at the root causes of the crisis and to look at it on all fronts.”