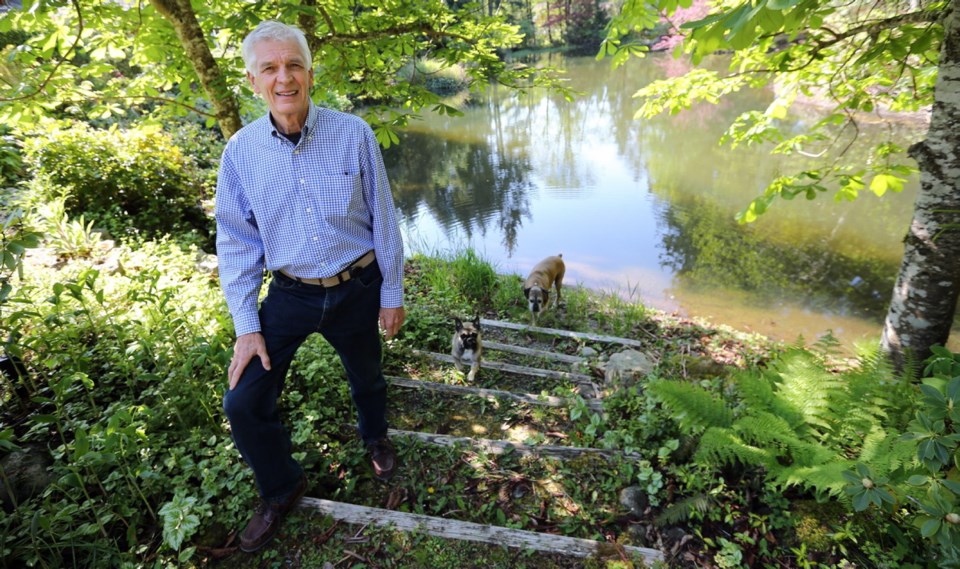

Retired anesthesiologist Dr. Martin Rodgers was treated with two days’ worth of antibiotics and told not to worry after he showed his family doctor a classic bull’s-eye rash caused by a tick he extracted from his navel.

That was three years ago this July. Now Rodgers, 74, once extremely athletic and active, is plagued by chronic fatigue, headaches, muscle and joint pain and insomnia while on a regular course of antibiotics from his naturopath.

Through a private laboratory in the United States, he tested positive for the bacteria, Borrelia burgdorferi, that causes Lyme disease.

“I am a physician and I wasn’t educated, so how can I blame other doctors who said ‘don’t worry about it, it’s not an issue’?” said Rodgers, who lives on the Malahat. He said medical boards and health authorities have inadequate education on testing and treatments.

Rodgers, a former family doctor, and those who say they have chronic Lyme disease are in the crosshairs of a debate about how many people actually have the illness and how many suffer from undiagnosed chronic and complex diseases that result in non-specific, but often disabling, symptoms including muscle pain, fatigue and weakness.

Bonnie Henry, medical director of the Vectorborne Diseases Program at the B.C. Centre for Disease Control, wrote in the B.C. Medical Journal in 2011: “There is no evidence to support an epidemic of Lyme disease in B.C.”

Provincial health officer Perry Kendall said there are about 15 to 20 lab-confirmed cases through the Centre for Disease Control in B.C. each year, while doctors report they are treating more than that.

Today, in Victoria’s Centennial Square from 2 p.m. to 4 p.m., two men from St. Catharines, Ont., will kick off a cross-country tour. They are trying to raise awareness about preventing, identifying and treating tick-borne infections like Lyme disease.

Childhood best friends Daniel Coroso and Tanner Cookson, both 23-year-old university graduates and former rowers, are embarking on a 58-day 8,000-kilometre bicycle trek, rideforlyme.ca, across Canada.

With their dads driving alongside in a 1986 Chevy RV, they plan to ride and raise awareness about the devastating effects of acute and chronic/late stage Lyme disease because of ignorance and inadequate testing and treatment regimes.

On Monday, they will be at Victoria’s Mile Zero at 6 a.m. to begin their journey, with the goal of reaching St. John’s, N.L., by July 7.

The trek is in honour of their friend Adelaine Nohara, 24, who, before being stricken with Lyme disease, played competitive soccer and ran marathons.

That changed in 2010. “Being a country girl, I thought nothing of the little tick I wrenched off of me in the shower . . . or the big round rash I (perhaps mistakenly) attributed to a spider bite years before,” Nohara writes on the Ride For Lyme website.

Untreated, a year later she felt so weak, physically and mentally, she was unable to walk or read.

“My legs quit doing what I wanted them to,” she writes. “Heart palpitations, tremendous air hunger and cardiac episodes left me wondering if I would wake up the next morning.

“According to science, had I been properly diagnosed and taken just a four-week treatment of antibiotics shortly after my tick bite, the incredible cost and misery of chronic Lyme disease could have been completely avoided,” Nohara writes. “Instead, it took 18 doctors and 18 months to get to the bottom of my illness.”

Coroso said Nohara is getting worse. “We visited her a couple of days ago, on our last night before leaving, and it was all she could do to stand up and give us a hug.”

Lyme disease has become one of the fastest-growing tick-borne infectious diseases in North America, Kendall said.

“It’s very important to be aware of ticks and to protect oneself from being bitten,” he said.

That includes wearing insect repellent, long sleeves and long pants tucked into socks in long grass, the woods and tick country, and checking for ticks when returning indoors.

Most of the tick activity, and 95 per cent of Lyme disease, is found in the central and northeastern part of the continent (Connecticut and to a lesser extent, Ontario, for example). The black-legged tick in B.C., ixodes pacificus, is different from the ticks in central and eastern North America, and is a less competent host. Only one in about 200 is found to carry the Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria, Kendall said.

Given the controversy over the testing in B.C. and climate change, which is causing ticks to move north to warmer and wetter habitats, the province added polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing to culture submitted ticks, a more sensitive way to detect the genetic material of the Lyme disease bacteria.

People suspected of having Lyme disease in B.C. may undergo a two-step process of testing — the enzyme-linked immunology assay (ELISA) and the Western blot test, which is used to confirm Lyme disease antibodies in people’s blood.

Kendall said most scientists, doctors, infectious disease specialists and health bodies understand the seriousness, cause and need for early treatment of acute Lyme disease

They do not, however, believe that, after an appropriate course of antibiotic treatment, the bacteria can hide in the body to produce chronic non-specific symptoms later, nor do they believe in the safety or effectiveness of long-term antibiotic use.

They agree that about 10 to 20 per cent of people successfully treated for Lyme disease have some remaining symptoms.

A much smaller number of professionals, backed by strong advocacy groups, are convinced that many people are suffering from chronic complex illnesses caused by undiagnosed Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria. They support tests in private labs in the U.S. that will test positive for Lyme disease, where tests in Canada prove negative, Kendall said.

In March 2013, the province funded the opening of a complex chronic disease program at B.C. Women’s Hospital and Health Centre. The program was established to assist people with fibromyalgia, myalgic encephalomyelitis (chronic fatigue syndrome) and tick-borne illnesses, such as Lyme disease, as well as to better research the causes and treatment of such chronic conditions and diseases.

What you should do if you are bitten by a tick: http://www.healthlinkbc.ca/healthfiles/hfile01.stm