It’s Victoria, 1978. Janice Forbes, an artistic, friendly single mom is strangled to death in her apartment while her kids play outside. Neighbours identify a strange man near the scene. An international manhunt leads to the arrest of a 20-year-old American named Tommy Ross Jr. He’s wanted in three similar stranglings but is tried and convicted here and sentenced to life. Ross, who is black, insists he is innocent, the victim of a racist time and a police conspiracy.

Nearly four decades later, in 2016, Ross is paroled and deported, then charged with another 1978 murder, of a young woman in Port Angeles, Washington. His trial could unravel decades-old murder cases and possibly lead to a wrongful-conviction claim in Canada. Or it could put Ross behind bars for life, bringing long-awaited closure to victims’ families from B.C. to California.

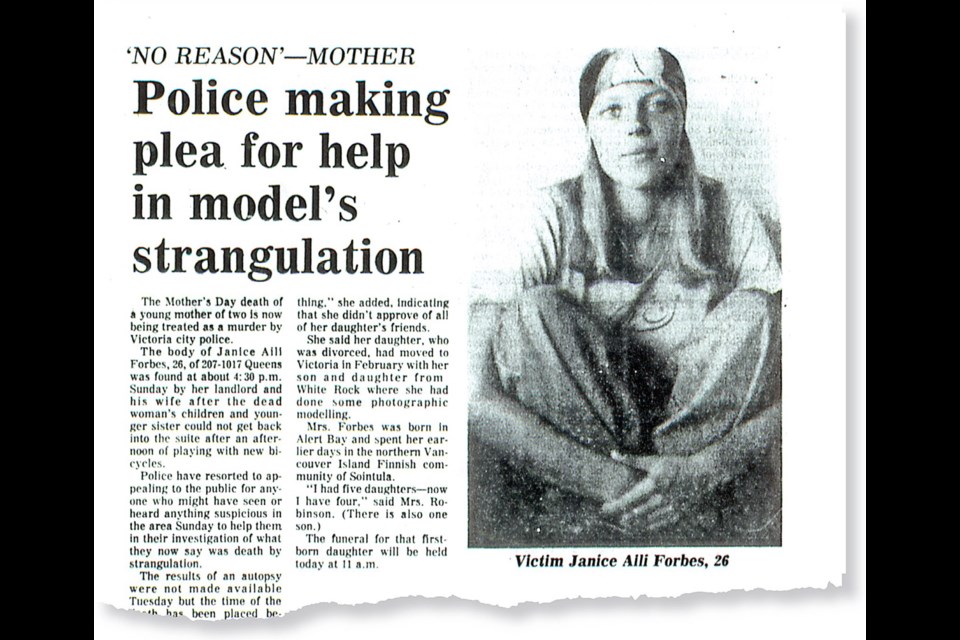

On an overcast Mother’s Day afternoon in 1978, a young single mother was found strangled to death, tied from her neck to her ankles in her Queens Avenue apartment while her children and sister played outside.

The brutal murder of 26-year-old Janice Aili Forbes gripped the city, where such sadistic crimes were rare, and kept downtown residents on edge as police searched for a suspect.

The key witnesses in the case were all children under the age of 12 who saw a man they didn’t know in the building, acting strangely.

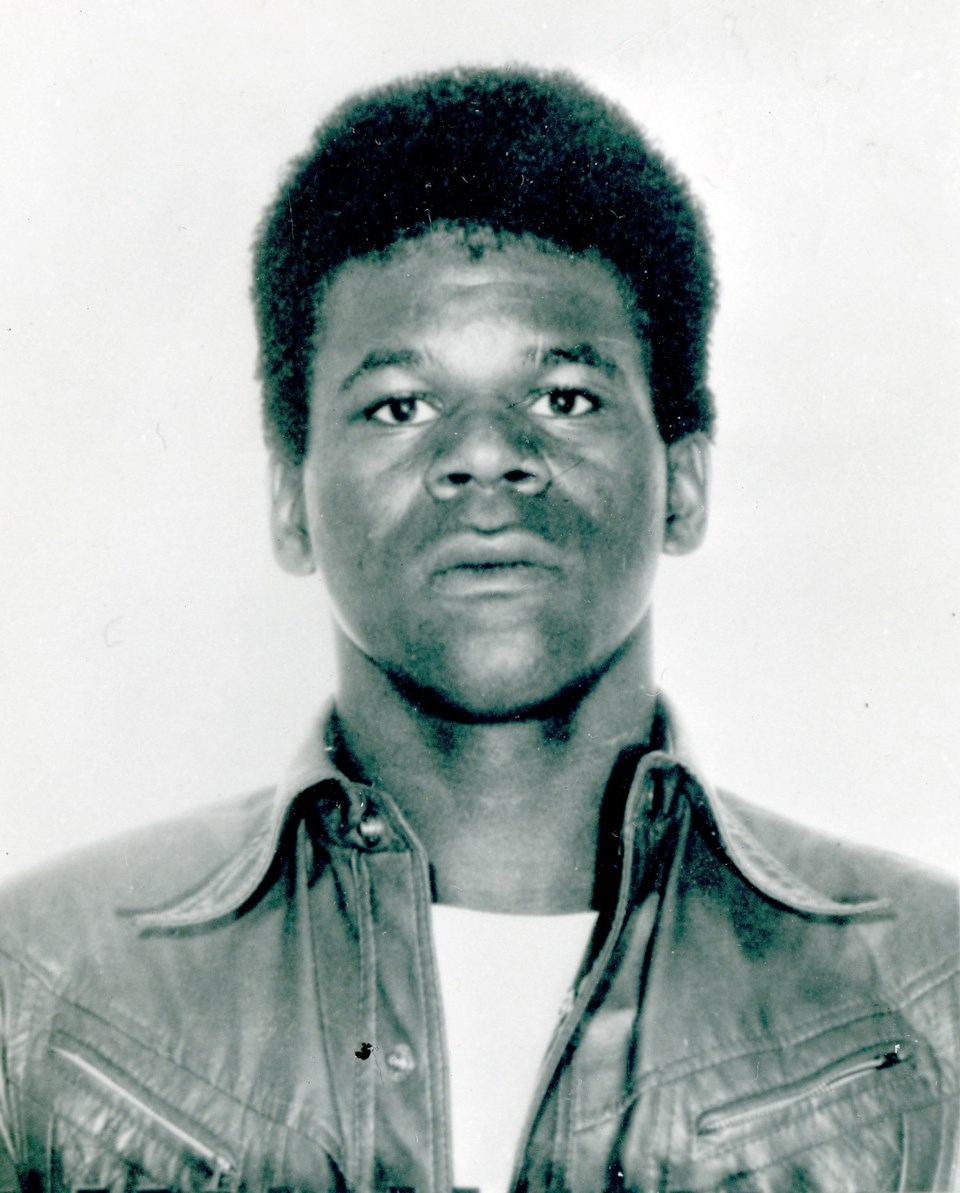

Tommy Ross Jr., an American who was visiting his brother in the Victoria neighbourhood, was identified as the man the children saw. His fingerprint was found in Forbes’ apartment. Within a year, he was tried and convicted of Forbes’ murder and sentenced to life in prison.

Last month, Ross was granted full parole after being denied several times for volatile behaviour. He has refused to admit he killed Forbes.

The parole board’s decision cited a tumultuous life of violence and crime, and grappling with racism. It also revealed concerns over the investigation of Forbes’ murder, racial bias and abuse in the prison system. Ross’s lawyer said there was credible evidence to pursue a wrongful conviction case.

Ross was supported by a law professor, a woman he corresponded with from jail, and his family — including a brother in Nanaimo who offered to support Ross if he was released.

Two detectives from Los Angeles and a prosecutor from Clallam County, Washington travelled to B.C. for his parole hearing; Ross is a suspect in cold-case murders that occurred in those jurisdictions before Forbes was killed.

The murder victims were all white single mothers, found bound and strangled in their homes.

The parole board chose to deport Ross, and he was taken to the Peace Arch border crossing. There, he was arrested and taken to jail in Port Angeles, where he has been charged in the 1978 murder of Janet Bowcutt. His trial is set to begin in the new year.

Ross could also be charged with murder in Los Angeles in the 1977 strangulation death of Bethel Woolridge. Ross maintains he’s innocent in all three murders.

All of these cases depend on evidence similar to that in the Forbes case: A fingerprint or someone who said they saw Ross in the area. The evidence was enough to convict in 1978, but will it be enough 40 years later?

How will allegations of systemic and police racism be heard differently today and weighed in a court of law? How will the prosecutors argue such similar cases in entirely different eras and social contexts?

If these murders are legitimately connected, could they be the work of an uncredited serial killer? And, if so, why did the U.S. authorities let Ross go, leaving the victims’ families in limbo for 40 years?

If Ross is found not guilty of the Port Angeles killing, which was used as evidence in the Forbes trial, could he make a stronger argument that he was wrongfully convicted in Victoria?

Most importantly, if Ross didn’t kill any of these women, who did? Are they still out there?

There was no known relationship between Ross and the three murdered women, but authorities argued indication of a motive might be in the similarities between the victims and how they were killed.

Murder on Queens Avenue

Janice Aili Forbes was by many accounts a cursed beauty.

“She was so much older, we were never really close but I always wanted to be around her,” said Tina Robinson, Forbes’ youngest sister by 14 years. “She was so pretty, so cool, such a hippie.”

Forbes was the eldest of five sisters and one brother. Robinson was the baby. The family came from Sointula, a tiny community north of Port McNeill founded by Finnish settlers in early 1900s as a socialist utopian experiment. Their mother’s lineage dates back to the original settlers and the family was related to most of the residents in the village.

“We grew up together and played all the time. We were best buds,” said Wendy Laughlin, an extended relative who still lives in Sointula. “She was very bubbly and friendly. I remember her visiting elderly people … but not always being allowed out to play.”

Laughlin said Forbes had a dual personality, outgoing in social situations but quiet and serious with those she was close with. “She lived here briefly with the kids and hung around with the hippies,” Laughlin said. “I always felt her other personality was a bit of a cover to show the world she wasn’t hurting.”

The last time she saw Forbes was in Campbell River a few years before she died. “Janice was a very artistic and talented person … she was beautiful too, with a heart-shaped face and strawberry blond hair,” Laughlin said. “At [her brother’s] funeral I threw a flower and said: ‘Take it to Janice.’ [Hers] is a life that should have never been taken.”

Beyond an evidence list from the B.C. Supreme Court, little primary documentation about the case is publicly accessible. Victoria police denied access to their files and did not answer questions about the murder investigation while they assist U.S. authorities on current related cases.

The Forbes case was covered by the morning Daily Colonist and the afternoon Victoria Times, which were combined into the Times Colonist in 1980. The original coverage is archived at the Times Colonist.

Forbes was recently divorced and looking for a fresh start in Victoria when she moved to the newly built apartment building at 1017 Queens Ave. in February 1978. Her six-year-old son stayed with her, but her nine-year-old daughter was being looked after by a nearby sister until Forbes could find a bigger place.

Forbes moved into the building in the same week that new building managers arrived. Bob and Jane Burke were also in their mid-20s, and had moved from Toronto a month after getting married. Bob Burke also worked as a burglar alarm technician.

“It was incredibly traumatizing”

Forbes and Jane Burke became good friends, and had coffee together nearly every morning. Forbes taught Burke to bake bread, do macramé and liquid embroidery.

“She was a really sensitive, generous person. We got to be close,” Burke said at the time, adding Forbes didn’t talk much about her past. “I never heard her speak ill of anyone, nor did she ever indicate she was afraid of anyone.”

Both Jane and Bob Burke mentioned that Forbes used drugs. Jane Burke said she saw Forbes use cocaine once, and saw her get a few joints from her sister.

Bob Burke testified in court that he did not like his wife’s friendship with Forbes, and did not like Jane smoking marijuana with Forbes. “I didn’t much approve of the use of drugs and she [Forbes] appeared quite proud of it,” he said.

Burke said Forbes grew marijuana plants on her deck and had showed him needle marks on her arms.

A pathologist testified that he found no needle marks on Forbes’ arms, although there were bruises. Her toxicology reports were clear and she was determined to be in perfect health.

In the few months Forbes lived in the building, there had been a rash of break-ins. Cash and a leather jacket were stolen from her apartment, while unoccupied apartments on the first and second floors were hit in three subsequent break-ins. On April 30, the Burkes’ apartment was broken into and about $800 in rent and petty cash was stolen. Bob Burke installed a deadbolt on their door and posted signs in the lobby asking tenants to lock their doors and to be cautious about allowing strangers in the building.

Jane Burke said that in April, Forbes was hired as a clerk with the provincial government. The day before she died, Forbes told Burke she had found a bigger apartment in a big old house across the street and was planning to move in July with both of her children.

That night the two friends went to the Jaycee Fair, a few blocks away on Quadra Street, behind the Memorial Arena. Forbes saw a necklace she liked and said she’d return Monday to buy it.

On Mother’s Day — May 14, 1978 — Forbes had planned a quiet Sunday at home with the kids, according to Bob and Jane Burke.

They told the Victoria Times that about 11:30 a.m., they stopped by Forbes’ second-floor apartment to drop off keys for an elevator repairman before heading to Nanaimo for the day. Jane Burke later told the court Forbes was not her usual cheerful self and appeared sad, or disappointed by someone she was speaking to on the phone.

Forbes met the elevator repairman just after noon. He said later that she seemed to be in good spirits.

About an hour later, two girls aged 10 and 12 came to the building to visit a relative. They said they saw a black man at the front entrance, holding the intercom phone. He asked one of them if they wanted to use the intercom and the younger one called her sister to buzz them in.

At the same time, Forbes’ daughter came to the lobby, holding a laundry basket. She pushed the front door open and the two girls entered, then held the door for the man to follow.

“I always wondered, had I not held the door for him would things have been different,” said the elder girl, Lisa, who still lives on the Island. She did not want her full name used because she is still afraid of Forbes’ killer. “Sometimes I open the shower curtain expecting him to be there. It’s terrifying.”

In her court testimony, she said she last saw the man she identified as Ross lurking by the mailboxes in the lobby but the image that sticks in her mind is an earlier one — as they were walking up to the building.

“He jumped out of an old yellow station wagon. It was as if it didn’t even stop. He was wearing a long coat that flowed behind him,” she said.

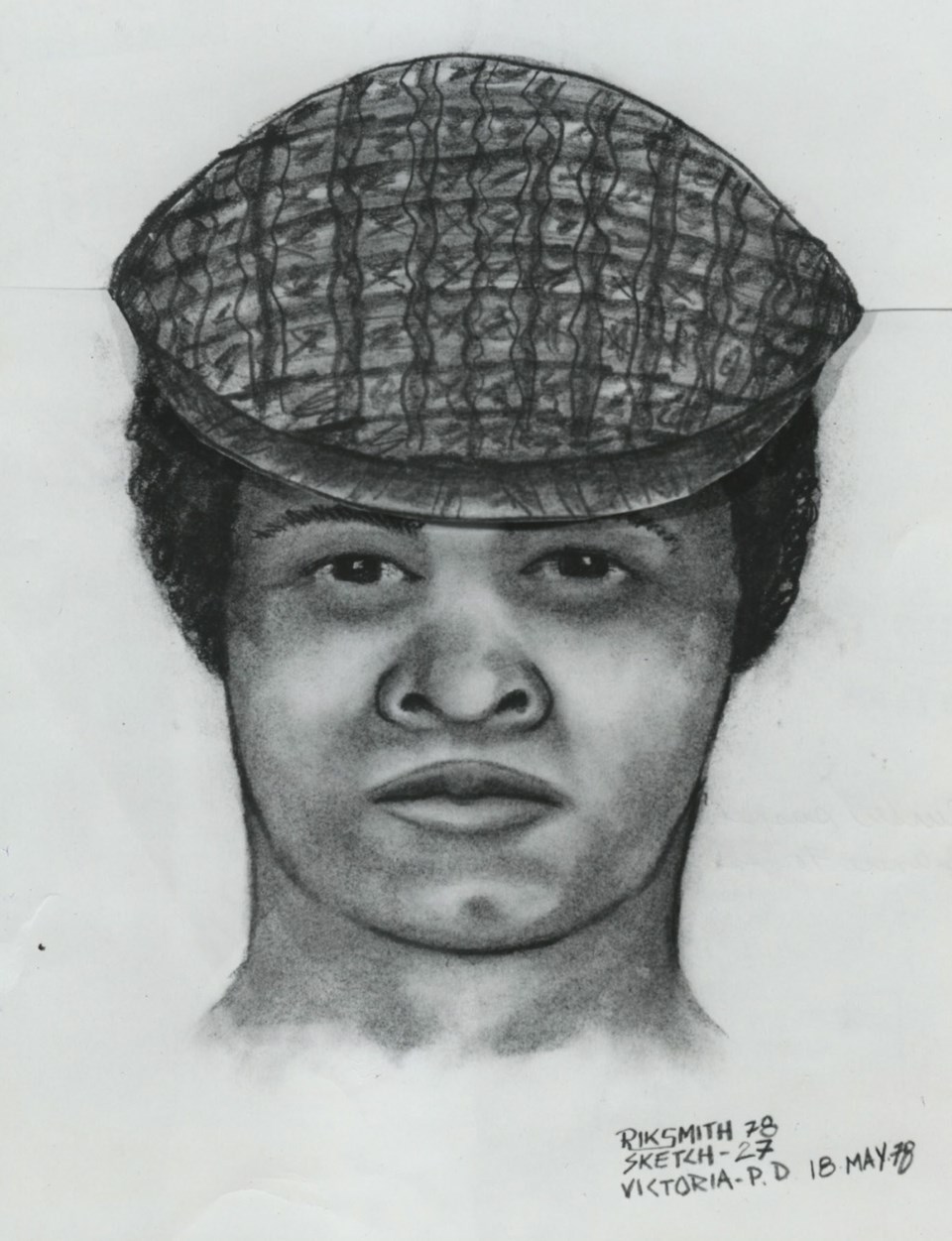

The girls’ testimony would become central to Ross’s trial, mainly because their descriptions a few days later helped create the composite sketch police used to identify him.

“I didn’t recall the hat but [the other girl] did,” she said. “I knew the man I saw that day. I had only seen a handful of black men but never up that close.”

During the trial, the girls were grilled during cross-examination about identifying Ross. One said she was not sure, then “pretty sure” it was Ross that they saw. The other girl said she was not sure when asked if anyone in the courtroom looked like the man she saw. It is not clear if she was directly asked to point out the man she saw in the courtroom.

“I remember [Ross’s lawyer Doug] Christie yelling at me, ‘You said this …’ and tears running down my face. He said if I didn’t get it right, ‘You go down instead of up,’ meaning to hell instead of heaven,” she said.

About 1:30 p.m., Forbes’ sister Tina Robinson arrived to deliver a Mother’s Day card and found Forbes’ children Kelly and Steven in the parking lot riding new bikes. She said Kelly went to deliver the card but the apartment was locked and her mom would not answer the door. So she slid the card under it.

“We weren’t really alarmed at that point. We just figured she went out so we went back down to play,” she said. “We took turns riding bikes. If someone had to go to the bathroom they went upstairs.”

Mary Robson, who lived two doors from Forbes, said in 1978 that she buzzed the children in about 2 p.m. and let them use her bathroom. Forbes’ daughter tried calling her mom. The kids played with a neighbour’s son for a while and went back and forth to the bikes in the parking lot a few times.

Robinson told the court on their last trip they “saw the man come out.”

“I still remember it was a door on the side of the railing. I was on a bike. He came out and jumped over the railing,” Robinson said. “He was in all black, black coat, black hat.”

Robinson said she remembers a negative feeling at this point. The kids tried knocking on Forbes’ door and looked through the peephole, saw shoes and heard music playing. They asked a neighbour to call the police but she was hesitant.

At about 4 p.m., the neighbour came across Forbes’ laundry in the communal dryers.

“She didn’t want to seem to get involved,” Robinson said. So the kids sat in a stairwell, killing time until the Burkes arrived about half an hour later and let them into the apartment with a master key. The children and Jane Burke went in first, and found Forbes’ body on the floor in the bedroom.

She was lying face down between the wall and the bed. Her wrists were tied behind her back and a dark pinstripe belt was tied around her right ankle to her neck — causing her body to be in a bow position. An officer said she was wearing jeans, a white and floral blouse and a light leather jacket. A torn bikini top and bottom were found nearby and some of her hair had been cut.

The Burkes got the children out and called the police. Victoria police Const. Robert Raappana, who was nearby on patrol, was first on the scene. He said Forbes’ neck still felt warm, and he cut the belt with a knife but couldn’t find a pulse. He called for an ambulance, but Forbes was already dead.

Robinson said she connected the man she saw jump the railing with what happened to Forbes.

“For some reason I had a key in my hand and decided to carve his face onto the back door. I don’t know why I did it but someone told the police,” she said. They didn’t have an artist in town so they got her to sketch another picture.

Robinson said her sister’s murder and the trial were devastating for her family, “which already had a lot of difficulties.” Her mother could not cope with the grief and shut down. Forbes’ children were sent to live with a paternal aunt after their father, remarried with a new family, rejected them.

“I think it was incredibly traumatizing. Life did not get better for them afterwards,” said Robinson, who lost contact with her nephew but stayed in touch with her niece for a few years.

Robinson said she has had recurring nightmares about Ross over the years and checked to see where he was in prison. She said she has always wondered if Ross was the right person, in part because she was so young when the murder occurred.

“It would be nice to see some DNA evidence to be sure,” she said. “But whoever killed my sister definitely killed that girl in Washington. It was just too similar.”

Baby on the bed

Three weeks before Forbes was murdered, a 20-year-old mother was strangled to death at home in Port Angeles, Washington. According to the Port Angeles Police Department, on April 24, 1978, Janet Bowcutt’s mother went to see her daughter and grandson.

They were living in what was then called the Pine Hill Apartments at 615 W. 8th St. The heritage building has one- and two-bedroom apartments and is close to downtown, next to Tumwater Creek bridge and overpass.

Bowcutt’s mother knocked on the door several times. After she heard her six-month-old grandson crying inside, she called the police.

Two officers arrived and one kicked open the apartment door. The other officer walked in and found Bowcutt dead on the bedroom floor. Her son was crying on the bed, unharmed.

Bowcutt was on her stomach with a scarf tightly wrapped around her head, securing a washcloth gag in her mouth. According to a police report: “The scarf was tied through the cordage around her ankles in such a manner that struggle would only tighten the scarf around her neck.” It was similar to the position in which Forbes was left.

Investigators found fingerprints at the scene, including one recovered from the inside of a brass and chrome doorknob; that fingerprint was later identified as belonging to Ross. When police canvassed the area, a neighbour named Violet Dominoski reported a black man she described as suspicious knocking on her door the week before. She later identified Ross in a photo montage.

Lee Meszaros, who lived across the hall from Bowcutt, said he saw Ross in the hall about 11:15 p.m. the night before Bowcutt died. Meszaros told a Victoria court he and his wife had just returned from their wedding in Seattle. He was running out to move his car, which had gifts inside, to a safer side of the building.

He opened the door to see a man he later identified as Ross standing about three inches away, facing him. He said Ross asked him if someone named Ducket lived in the building. Meszaros told him to check the mailboxes or ask the manager.

Meszaros then realized he had forgotten his car keys and went back inside. When he came out several minutes later, Ross was still there.

“When Meszaros saw him, the male feigned as if he was looking at the mailboxes (but it was obvious to Meszaros that he was not),” said the police report.

Meszaros testified as a witness in the Forbes murder trial and told the court, “After talking to him, I figured he was going to rip somebody off,” said Meszaros. “So I went out and moved my car … He was very polite, like he had been caught at something.”

Port Angeles police said they were contacted by Theodore (Ted) McDonald a few weeks after Bowcutt and Forbes were killed.

Extreme racism

McDonald was Ross’s half-brother and a cook at the hotel where Bowcutt worked — which might be the only loose link between Ross and any of the victims.

McDonald and another brother who lived in the area told police they thought their youngest half-brother, Ross, might have been involved in the murders.

He said Ross, originally from Pacoima, California, had stayed with him in Port Angeles from April 15 to 27 or 28. McDonald gave his brother bus money to leave Port Angeles. He saw him again in Victoria on May 12 when the three brothers were visiting a fourth brother, Raymon McDonald.

Ted McDonald said the brothers went clubbing and the last time he saw Ross was May 13, the day before Forbes’ death. He told police at the time that his younger brother “had a violent history and a hatred towards whites,” the report said.

Police discovered a warrant for Ross’s arrest in a rape and burglary in Los Angeles, though they did not say how. Ross was also a suspect in the 1977 murder of another young mother, strangled to death at home in a similar manner to Forbes and Bowcutt.

A footnote in the crime report

On Nov. 8, 1977, Bethel Woolridge was murdered at her walk-up apartment at 12601 Pierce St. in Pacoima, one of the oldest neighbourhoods in Los Angeles.

Woolridge, 36, was a single mother raising four children between the ages of seven and 14. She was killed after her children went to school.

The Los Angeles Police Department said she was found “bound with her hands behind her back and strangled with an electric cord wrapped several times around her neck in the bathtub.” About the same time, a rape, burglary and attempted rape and burglary occurred in the same complex.

Ross had been seen in the area by other apartment dwellers and was considered a suspect.

Woolridge’s death was little more than a footnote in the Los Angeles Times crime report. What became of her children afterwards is not known.

According to the Victoria Times on June 8, 1978, Victoria police said the Ross investigation reopened several other murder cases in the U.S. The Ventura Police Department said there were several unsolved strangulations of young women in Santa Barbara, Ventura and Los Angeles. San Diego also had the March 14, 1978 strangulation death of a young woman.

By mid-June 1978, Ross’s photo was circulated from Sacramento to Port Angeles and Victoria. He was identified by witnesses in each area. On June 30, the FBI crime lab released a report identifying the middle-finger print on the inside of the doorknob at Janet Bowcutt’s apartment as belonging to Ross.

A warrant for Ross’s arrest was issued by Clallam County, and he was arrested by the Los Angeles Police Department on Dec. 22, 1978, at Community Hospital in North Hollywood.

How Ross, a suspect in murders in two states as well as rape and robbery was sent to Canada to face a murder charge is a bit of mystery — especially since some of the country’s most notorious serial killers were operating in California and Washington at the time.

The Hillside Strangler murders, committed by cousins Kenneth Bianchi and Angelo Buono, saw girls and women from Los Angeles to Bellingham kidnapped, raped and strangled from 1977 to 1979.

Rodney Alcala, also known as the Dating Game Killer because he had been a contestant on the TV show, was also an active serial killer and was in both California and Washington state. He photographed and strangled his victims, young women and men. He was arrested in 1979.

“Something just doesn’t add up there,” said Raymon McDonald, Ross’s elder brother. “If Tommy was a serial killer, why did they let him walk out?”

McDonald has maintained his brother’s innocence for nearly 40 years and believes he was used as a scapegoat for investigators who fabricated evidence.

“I have a lot of questions, loads of questions about what went down,” said McDonald, a high school counsellor in Nanaimo, who has spoken about his brother’s case and incarceration as a learning tool about the judicial system and racism.

“When I watched the trial I was convinced he would be released. No eyewitness could clearly identify him. My brother and I look nothing alike and when I walked into the courthouse some [people] thought I was the person [on trial],” McDonald said. “Tommy came back to Canada voluntarily because he hadn’t done anything wrong.”

Tommy Ross Jr.

Tommy Ross Jr. grew up in Los Angeles at a time that was not easy for young black men.

The 1960s saw the signing of the controversial Civil Rights Act, prohibiting discrimination based on race and gender, as well as the rise of the Black Panthers and the Watts riots, which were sparked by racial tension over a lack of access to housing and jobs as well as allegations of police brutality.

“It was terrible. Much worse than it is now,” said Raymon McDonald. “I made up my mind around 14 or 15 years old, I did not want my future children to grow up there. That’s why I moved to Canada.”

Ross, born in 1958, is the youngest stepbrother in a large family. He told the parole board this year that he was raised in a stable, pro-social family and that his mother taught good values.

But Ross also said he was subject to extreme racism when he was young. He had a learning disability, later diagnosed as dyslexia, that prevented him from reading and writing so he skipped school at a young age. The parole board described his childhood as chaotic and him getting involved in the judicial system before he was 10 years old.

“You said you grew up during segregation and gave examples of a relative being hanged by a mob, black children having to swim in ditches while white children had a swimming pool and not being allowed to use change rooms in clothing stores. You told the board you developed a sense of anger,” said the parole board in its decision.

“You got involved in criminal activity when you were young and committed property and violent offences. You have also admitted being involved in gambling, drugs and living off the avails of prostitution. According to file information, violent offenses included robbery, shooting a person with a pellet gun and stabbing another resident at a youth correctional facility.”

Ross told the parole board he stabbed a white inmate in 1975 in retaliation for the stabbing of a black inmate.

Ross said he was in Port Angeles and Victoria at the time of the murders in 1978, “but adamantly denied killing either victim.” He said he stopped in Port Angeles to see a brother and came to Victoria for the weekend to see another. According to police at the time, Ross was a frequent visitor to both places.

He came to Victoria on the Coho ferry in early May and stayed with McDonald, a block from Forbes’ home on Queens Avenue.

Ross was spotted by two women in the area the day Forbes died. The first lived in a building near McDonald, but didn’t know him or Ross. She said a man she later identified as Ross came to her Queens Avenue apartment about 11:30 a.m. wearing a dark, long leather coat and black hat.

The man asked about places to stay in town. They spoke for a few minutes in the doorway and he left, but returned 15 or 20 minutes later and asked the same questions. The woman told him he’d already been there and he said he forgot. A newspaper article said, “Her strongest impression of his demeanour was one of tension, from his stance and stiff arms and the redundant conversation.”

When she was asked about identifying Ross from a police sketch, “she said she couldn’t remember if the sketch was similar to the facial features of the man at the door, but the obvious similarities were that both were black and wore caps, and the appearance agreed with her recollection,” the Daily Colonist reported in June 1979.

Another woman, who was dating Ross’s brother from Bellingham, told the court she saw Ross about 2:35 p.m. that day walking to McDonald’s apartment from the opposite direction of Forbes’ apartment. She said he was wearing a long, dark jacket and tuque but seemed normal and relaxed. He went to grab his clothes and she gave the brothers a ride to the Swartz Bay ferry terminal.

The woman said she was questioned by Victoria detectives for nine hours and felt pressured to say she saw Ross coming from a different direction. She told the court she alerted police to another black man called Tommy Cheek hanging around her work a few days later.

“He seemed to know me. It bothered me,” she said. Police did not say if the man was a suspect but coincidentally he was the first pick from a photo montage shown to at least one of the witnesses at Forbes’ apartment.

“He lived in the area and he looked a lot more like the composite drawing,” said McDonald, who knew Cheek. “All of a sudden this all happens and he’s gone, never to be seen again.”

McDonald said at that time there were very few people of colour in Victoria, but racism and ignorance were evident.

“People might cross the road if they saw you or lock their car door,” he said. He formed a group called People Against Racism and Discrimination. “We held forums and stuff to make people more aware.”

Wanted man

It’s not clear how police in Victoria, Port Angeles and Los Angeles were turned on to Ross as the primary suspect in three murders. The tip from Ross’s brother in Port Angeles is the first reference to a connection.

According to 2016 Port Angeles certification for probable cause, just after Forbes’ death the police noted key similarities between the murders: All three victims were single, white mothers with no men living with them. They were killed at home with a similar signature method — strangled, gagged and bound around the neck several times and tied from neck to ankle. None were sexually assaulted. And all were clothed but not wearing bras.

On May 25, 1978, nearly two weeks after Forbes was killed, Victoria police released a composite sketch of their suspect. They did not release a name but said the suspect could be connected to the Port Angeles murder and one in San Diego.

By June 1, Ross’s fingerprints and mugshots were sent from Los Angeles to Port Angeles and Victoria. His fingerprints were also sent to the FBI crime lab. Ross was identified by Meszaros in Port Angeles and later by his fingerprints on the doorknob.

On June 8, Victoria police released Ross’s name and announced they were part of an international task force looking for the 19-year-old. He was described as “extremely dangerous” and “probably armed with a knife” said a story in the Times.

Port Angeles police said at the time Ross was one of several suspects and issued a warrant for his arrest. California police said they were investigating several unsolved stranglings of young women.

By July 8, Ross was the prime suspect with charges pending in the first-degree murder of Forbes. His photo was released, and it was reported he had last been seen in Bellingham around May 26.

“I certainly remember that case. It was a big case,” said Fred Mills, a retired Victoria police detective. He said there was a sense of fear in the city with a killer at large. “We threw an awful lot of resources at it, trips to Port Angeles to compare notes. It was high profile. You have to get a break somewhere along the way and we did.”

On Dec. 22, Ross was tracked down at the Community Hospital in North Hollywood and arrested by Los Angeles police. He denied being in Port Angeles at all that spring.

According to an article in the Colonist on Dec. 24, 1978: “Victoria police said arrangements were being made through the B.C. attorney general to begin extradition proceedings in California but Ross was wanted for murders in San Diego, California, and Port Angeles, Washington, and it was expected those charges would have priority over foreign ones.”

So how did Ross, wanted for two U.S. murders, a possible suspect in others amidst a rash of young women being mysteriously strangled to death, end up facing charges in Canada?

Apparently, he volunteered.

According to a Jan. 14, 1979 article in the Colonist, Ross waived extradition proceedings and voluntarily came to Canada to face charges, accompanied by two Victoria detectives — including Doug Richardson, who later became chief of police.

Both Clallam County and Los Angeles waived their charges in favour of Ross going to Canada.

At the time, California had reinstated the death penalty for murder.

McDonald said his brother came back to Victoria because he was innocent.

“He voluntarily came because he didn’t do anything,” said McDonald. “Why would they release him if he was seriously a suspect?”

On Jan. 15, 1979, Ross was formally charged with murdering Forbes.

The trial

The murder trial of Tommy Ross Jr. began on June 19, 1979, with a packed courtroom, tight security and a jury made up of seven men and five women. The trial centred largely on circumstantial evidence, a controversial fingerprint on a teapot and the rare allowance of evidence from the Bowcutt killing. There were no clear motives and no eyewitnesses to the crime.

“For me, it was just another murder trial to cover. But what stood out was the moving fingerprint,” said Roger Stonebanks, a reporter for the Victoria Times at the time. “I don’t think I’d even heard of that before or since. The prosecutor poured a lot of cold water on that one.”

On the second day of the trial, Ross’s lawyer Doug Christie argued the fingerprint found at Forbes’ apartment was planted there after Forbes was killed — likely by police. Christie, then in his early 30s, would go on to defend high-profile clients — including a Holocaust denier and former Nazi prison guard.

The green glass teapot, used by Forbes to keep loose change, was not discovered by detectives until nearly a month after she was killed. Sgt. Patrick Braiden, who was then head of the identification section, told the court he did not see the teapot with Ross’s fingerprint until his fourth visit to the crime scene, on June 10.

Another officer alerted him to the teapot, which was sitting on top of a dresser in the bedroom. Braiden said he likely did not see the teapot because it might have been covered by a scarf.

He testified he picked up a child’s belt next to the teapot on his first visit to the apartment the day Forbes died. He didn’t photograph the dresser that day because some things had been moved, he said. The clear right thumbprint and partial palm and fingerprint on the teapot were the only prints found in the apartment, which Braiden said was normal for a crime scene.

When Christie asked Braiden if a print could be transferred with Scotch tape, he said it could, but would not remain as clear as the one on the teapot. Cross-examined again the following week, Braiden said eight clear fingerprint points eliminated it as a forgery, which is why he did not have it further analyzed.

“I say positively that there was no adhesive on that handle,” Braiden told the court, and said comparing the thumbprint to Ross’s on file, “it is one and the same, made by the same person.”

Christie suggested the fingerprint evidence was part of an international conspiracy and that Victoria police might have obtained Ross’s print on a visit to a former residence in Washington.

He argued the fingerprint was the only evidence that tied Ross to the Bowcutt murder in Port Angeles, which led to the judge to allow the similar case to be considered in the Forbes trial. Witnesses from Port Angeles and evidence were presented at the Victoria trial despite the fact the original warrant was waived, no charges were laid and Ross had never been tried for the Port Angeles crime.

According to a story in the Colonist on July 6, Justice Alan McFarlane told the jury to conclude Ross was guilty of the Bowcutt murder and then consider the similarities with Forbes’ death.

“You will be asked to conclude that it was the same man in both cases and that the accused was that man,” McFarlane said. “Circumstantial evidence must not be consistent with guilt but inconsistent with any other conclusion.”

Christie said the evidence from the Port Angeles case, “if it had stood alone, would not have properly hung a dog, but is introduced here to hang a man on another matter.”

On July 13, 1979, the jury found Ross guilty of first-degree murder after five hours of deliberations. He was given a mandatory sentence of life in prison with no chance of parole for 25 years. The judge asked if he wanted to say anything, and Ross declared he was innocent.

“I have been found guilty of something I did not do … It was the same of Jesus Christ, he was accused of something he didn’t do. Something was passed on to him,” Ross told the court.

“I don’t know when, maybe tomorrow, maybe next week or next year, it will come out who did it … Nothing stays in the dark forever … No matter what nobody says, I am innocent. Thank you.”

Locked up

After losing two appeals, Ross served 37 years in federal prisons before being granted full parole and deported on Nov. 10. He was not an ideal prisoner, according to the parole board, but expressed concerns about his trial and treatment while incarcerated.

“Your institutional behaviour has historically been poor, although it has improved in recent years,” said the parole board in its decision.

Ross spent several of his early years incarcerated in maximum security with stints in segregation and special-handling units. In the late 1980s, he was awarded a monetary settlement by a human rights tribunal for mistreatment by Corrections Service of Canada staff.

In 1988, Port Angeles police and a Clallam County prosecutor visited Ross in a Saskatoon prison. According to a certificate for probable cause issued to arrest Ross after his parole, he admitted in an interview that he killed Bowcutt, as well as two women in Anaheim and one in Los Angeles.

He refused to give any further details unless the men could guarantee he would get the death penalty.

“Ross showed no remorse for the killings and stated that if he had to do things in his life over again, he’d do everything the same way,” said the order.

In 1995, Ross tried to get access to his trial files, but was initially denied by Victoria police and then by B.C.’s information and privacy commissioner.

The Times Colonist reported that Ross told then-commissioner David Flaherty he wanted witness statements and mugshots, “at that kangaroo trial they gave me. I’m asking for the statements [witnesses] gave to the police … I’m also asking for notes by police on this 1978 murder. That’s what I want, point blank.”

He also said the thumbprint “was planted in that damn apartment.”

At the time, now-deputy police chief Steve Ing argued successfully that Ross should be denied the information because he was a safety risk and could harm legal proceedings. It is not clear what those proceedings were.

Ten years later, Ross was convicted of aggravated assault in prison for stabbing another inmate with a homemade weapon in 2003. In 2013, Ross was convicted of assault with a weapon after swinging a crutch at a correctional officer.

Ross was denied parole in 2007, 2011 and 2014.

The parole decisions listed examples of volatile behaviour by Ross, including violent outbursts and locking himself in his cell with a razor blade to his neck. On one occasion this year, Ross became so upset at being told to submit a request in writing (he is functionally illiterate) he kicked and smashed a glass door, then said he didn’t mean to.

When he was told he was going to be sent to segregation, Ross took a razor blade from his pocket and slashed his neck several times. He was flown to hospital and spent the rest of his sentence at the Pacific Institute Correctional Centre in Abbotsford, which has mental-health services for prisoners.

He told the parole board the first time he assaulted another prisoner was to avoid being raped, but he was the one who ended up in segregation.

“You said you had learned to be pre-emptively violent to survive and you adopted an attitude that condoned the use of violence,” the board stated. Ross made progress in recent years, acknowledged the parole board. He completed two programs for violent offenders, including some written work, held various jobs at the institution and intervened to protect vulnerable inmates.

However, Ross’s case-management team did not support full parole and said his progress was too recent to mitigate risk.

His parole officer described Ross’s behaviour as “demanding, angry, manipulative and entitled,” but said he had the ability to calm himself down.

Ross has also maintained a positive relationship with his family, including visits, throughout his incarceration.

“We’ve always believed in him,” said his brother Raymon McDonald, noting his 84-year-old mother in Sacramento sent birthday cards and letters and hopes to one day have Ross back home.

McDonald said years of imprisonment for something he didn’t do has worn his brother down.

“He’s dealing with it the best he can,” McDonald said. “I think the parole board listened to his concerns well.”

McDonald said his brother’s bid for parole was likely helped by a presentation from Michael Jackson, a law professor and advocate for prisoner’s rights from Vancouver.

Jackson detailed several concerns with Ross’s case, including what he believed was inherent racism in Victoria in the 1970s and a wrongful conviction. Ross’s counsellor also said racism was “a real presence” in those days in the prison system, and some inmates were treated horrifically.

The parole board said it found Ross’s case to be difficult and highly unusual, requiring non-traditional analysis. It said it must recognize the contextual factors relating to racism and an alleged faulty police investigation.

“There is reliable and persuasive information that you have been subjected to racism before and during your sentence,” the board told Ross. It also said it agreed that there were “serious concerns with respect to the integrity of the police investigation.”

In awarding Ross full parole, the board noted it did not consider him being a person of interest in the U.S., but made the deportation order as part of the parole plan.

If Ross wants to return to Canada, his parole conditions require him to notify Corrections, enroll in mental-health counselling, take medication and reside at an approved residence.

McDonald said he had offered to have his brother live with him in Nanaimo if he wasn’t deported. If Ross is released in the U.S., he told the parole board, he’d like to live with his mother and would be eligible for social assistance because of his learning disability.

He also has a girlfriend who supports him.

“He can’t read or write, but he’s one of the smartest people I’ve met,” said McDonald. “He understands a lot of things about life.”

The next chapter

Since he was deported and arrested in the Bowcutt murder, Ross has been in jail in Port Angeles. His bail was set at $1.5 million and he was formally charged with killing Bowcutt on Dec. 2.

He appeared in court shackled at the wrists and waist, with one public defender bowing out because of a conflict of interest with a potential witness and another stepping in a week later.

Clallam County brought former elected prosecuting attorney Deborah Kelly back from retirement to handle the case because of her history with complex homicide cases such as the one involving Darold Ray Stenson.

Stenson was convicted of killing his wife and business partner in 1994 and sentenced to death. Just eight days before Stenson was scheduled to die, his execution was stayed and the verdict overturned, and he was awarded a new trial. In 2013, he was again found guilty and sentenced to two life terms.

Kelly is being assisted by Clallam County deputy prosecutor John Troberg, who travelled to Canada for Ross’s release and has been working with Los Angeles detectives still interested in Ross as a suspect in the killing of Bethel Woolridge.

“This is still an open investigation,” said Det. Kenneth White of the Los Angeles Police Department unsolved homicide unit. “We’re very interested in speaking to Mr. Ross.”

White could not say if they had forensic evidence linking Ross to Woolridge’s death or if any of her children or family are around, waiting to find out who brutally killed their mother 39 years ago.

In Port Angeles, prosecutor Kelly said the expectations of juries are different today than they might have been in 1978.

“Forensic shows like CSI definitely raise expectations for evidence,” said Kelly, who is expected to introduce DNA evidence for the first time in the murders, using nail clippings. “It’s also possible tests run then are not done to protocols today,” she said.

Victoria Police Det. Keith Lindner said that while murder investigations are much different now than in the 1970s, due to changing technology and legal thresholds, fingerprint evidence is much the same.

“The basic concept is the same,” said Lindner, adding pattern and points are still used to analyze prints. “Now we use scanners instead of ink pads,” and prints can be stored and searched electronically instead of on index cards.

Kelly said more investigation is needed, but the Bowcutt murder is still a viable case, although there are unique challenges with a case nearly 40 years old.

“Some of the people who gave statements then are deceased,” she said.

Lane Wolfley, Ross’s court-appointed lawyer who specializes in personal-injury law but also does criminal defence, said some witnesses will still be available.

“I recognized a few names on the list as people around town,” he said.

“He’s adamant he’s innocent,” Wolfley said. “We’re gearing up for a trial.”

The trial of Tommy Ross Jr. for the murder of Janet Bowcutt in 1978 is expected to begin on Jan. 30.

![janiceforbes[1].jpg](https://www.vmcdn.ca/f/files/glaciermedia/import/lmp-all/969862-janiceforbes-1.jpg;w=960)