It was one freaky Friday in the world of astronomy.

Not only did a meteor explode above Russia, injuring 1,100, but an asteroid came closer to Earth than at any other recorded time in history.

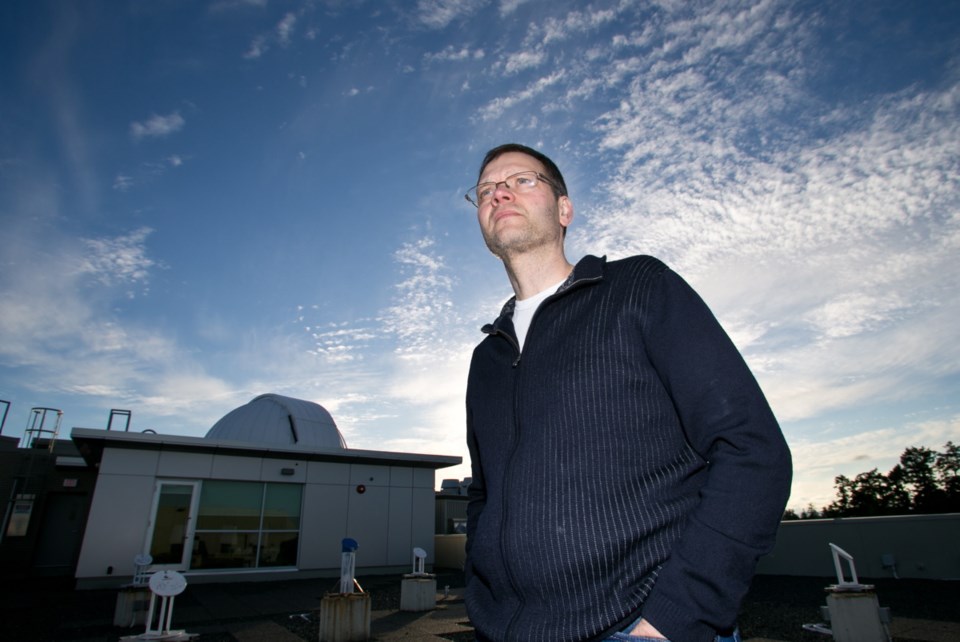

“They were certainly within 24 hours of each other and certainly Friday in both locations,” said JJ Kavelaars, an astronomer at the Herzberg Institute of Astrophysics in Saanich.

Asteroids are large rocky objects that are smaller than a planet; meteors are chunks of asteroids that make it as far as Earth’s atmosphere. Size-wise, the moon has greater mass than all half-million known asteroids combined, Kavelaars said.

The Russian meteor that exploded 30 to 50 kilometres above Chelyabinsk is something that happens only once every 100 years — the last one was in 1908, also in Russia. Called the Tunguska event, it flattened 80 million trees and measured about 20 metres in diameter. NASA’s website says that fireball released as much energy as 185 Hiroshima bombs.

Friday’s meteor was about 15 metres in diameter and weighed about 7,000 tonnes, Kavelaars estimated.

Its velocity when it entered Earth’s atmosphere was 18 kilometres a second, creating a shock wave heard as a sonic boom. Unlike many meteors, this one entered the atmosphere at a shallow angle, spreading the sonic boom over hundreds of kilometres, Kavelaars added. It was the sonic boom that caused windows to break, which in turn caused injuries — but no reported fatalities.

“There have been no reported deaths from meteor impacts, ever,” said Kavelaars, who also teaches at the University of Victoria.

The upside to the meteor explosion will be the scientific knowledge gained about the number of such objects in local space — a few million kilometres around Earth — and “the collisional likelihood” of them making contact, he said.

Kavelaars hopes some of the meteorites end up in scientific hands.

“Studies of exactly how it exploded, what was the amount of energy that was involved, help us understand the hazard better,” he said. “Now we can really understand whether the way we thought these events would occur is how they do occur.”

Friday’s asteroid — 2012DA14 — was predicted about a year ago by a Spanish survey of the night sky. It came closest to Earth at 11:24 a.m. PST Friday and at 27,650 kilometres away would have been visible with binoculars from anywhere in Australia.

“That’s very close,” Kavelaars said. “Anything that gets within a few million kilometres of the Earth, we call that near.”

Space objects that are one kilometre in diameter pose the biggest risks.

“If they hit the Earth, it’s a pretty bad day for everybody,” Kavelaars said. “And there’s quite a few of those. [But] the likelihood of that is almost zero.”

That’s because scientists generally know where these large objects are and no close encounters are predicted in the next few hundred years, he said. There are strong correlations between huge impacts and mass extinctions, but these occur tens of millions of years apart — or longer.

In contrast, the catalogue of objects not much larger than the Siberian meteor is “very incomplete,” Kavelaars said, and there are are millions of them out there.

The Canadian military, in co-operation with the Canadian Space Agency, is expected to launch the Near Earth Object Surveillance Satellite in the near future. “And NEOSAT will actually make a big dent in trying to find those objects.”

The Siberian meteorite would have been visible for only a few hours before hitting Earth’s atmosphere but with enough research, such events could be predicted and warnings undertaken in the future, he added.

“There is work going on to mitigate the risks,” Kavelaars said.