The federal fisheries department is asking commercial fishermen to voluntarily avoid nine reefs in the Strait of Georgia while talks are underway to make the fishing closures official and help ensure protection of fragile glass sponges — possibly the “longest living animals” in the world.

“Until these protection measures are finalized, DFO is requesting voluntary avoidance of these sponge reefs from all bottom contact fishing activities ... in the area,” the department states in a memo. Fisheries would include groundfish trawl and longline, shrimp trawl, and crab and prawn traps.

If protection is afforded to the nine sites, it would represent “the most positive thing we’ve seen in marine conservation in B.C. in a long time,” says Roy Mulder, president of the Marine Life Sanctuaries Society and one of the conservation groups involved in the talks. “I’m really impressed we’re finally seeing some action.”

Two meetings have been held so far among federal, industry and conservation groups, with two more planned for July and September. Commercial representatives are going back to their respective organizations to discuss the proposed closures, while federal officials undertake separate discussions with aboriginal groups, Mulder said.

Also being debated are 200-metre buffers around the reefs.

Chris Sporer, executive director of the Pacific Prawn Fishermen’s Association, representing the spot-prawn trap sector, said members have been informed of the DFO request and it’s up to individuals whether to comply.

“We recognize this is an important initiative and we are committed to the process and working with DFO. We’re looking for ways to protect these special features while minimizing the impacts on commercial fishing families.”

He noted that effective this year as a condition of licence, prawn-trap fishers must have a GPS-based monitoring system on board that records the vessel location every 15 minutes and records when a fisher sets and hauls in gear — all to ensure that fishing does not take place in closed areas.

Mulder said the current thinking is that the nine sites would be protected from fishing through “variance orders” that would be renewed annually rather than as official marine protected areas as early as 2015. “That always makes me nervous, it leaves the door open to pulling the plug on it almost overnight. But as a first step ... it’s a really good thing.”

The exact size of the nine reefs was not immediately disclosed.

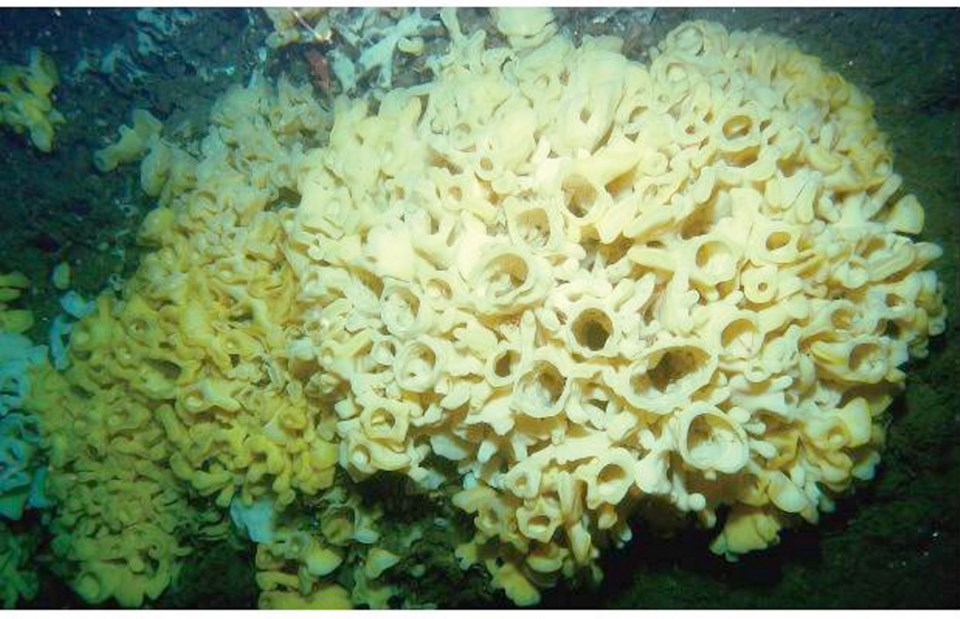

Glass sponges have silica skeletons and serve as refuges for juvenile rockfish and invertebrates while filtering impurities in the ocean water. They are easily damaged by trawl nets, the lowering of crab and prawn nets, as well as sport fishing gear trolled along the ocean bottom. Siltation from fishing activities can restrict the sponges’ ability to filter water for hours or days.

Federal documents say the nine reefs are “significant” with “low economic impacts” associated with them being closed to fishing. Glasses sponge reefs were common 200 million years ago during the Jurassic period and are “possibly the longest living animals in the world,” according to the documents. Today, they exist only in B.C. and Washington state.

Reef complexes can be up to 19 metres high and several kilometres wide. They were first discovered in Hecate Strait and Queen Charlotte Sound in 1987-88, where the reefs are thought to be about 9,000 years old, and over the past dozen years in the Strait of Georgia. They grow about one to two centimetres per year on average.

The Vancouver Sun raised the issue of the threatened sponge reefs in a story in April 2013 and in October 2013 dove to the bottom of Howe Sound to view the structures on a Nuytco Research Ltd. submersible.

Canada is committed to protect ocean biodiversity through the Oceans Act of 1996 and internationally through the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity of 1992.