While Seattle Seahawks cornerback Richard Sherman got himself in hot water last month with all his trash talk, Andrew Naysmith isn’t worried he’ll face a similar fate tonight.

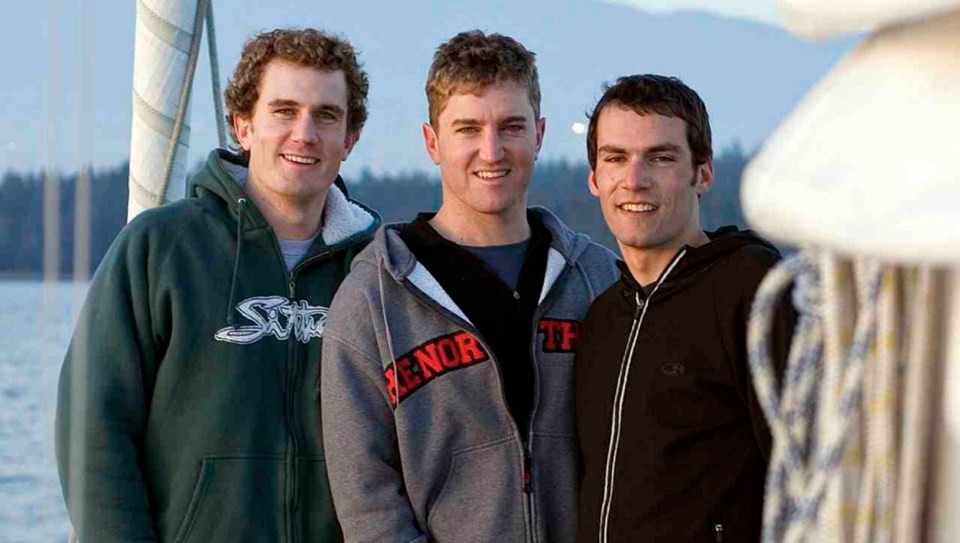

The Victoria director won’t be the only guy talking trash after the 8:45 Victoria Film Festival screening of his documentary Tide Lines at the Vic Theatre. So will three UVic engineering grads in their 30s — brothers Ryan and Bryson Robertson, and close friend Hugh Patterson — as they recount how they took out the garbage during their three-year voyage of discovery around the world.

Tide Lines, which Naysmith co-produced with Arwen Hunter and David Malysheff, is an engaging and enlightening journey that documents how the trio’s dream of circumnavigating the globe in their 12-metre sailboat Khulula, with lots of time out for surfing, became an adventure more life-changing than they could have imagined.

READ MORE Coverage of the Victoria Film Festival

It turned into a global ocean-protection expedition.

Naysmith, 36, a surfer like his buddies, remembers sharing their concern over the mystifying amount of garbage they began noticing in desolate surfing spots such as Sombrio Beach.

“The guys were saying, ‘Let’s go see if it’s everywhere else,’ and I had the same question,” said Naysmith, telling his pals when he realized they meant business: “I hope you’re taking a camera.”

In its early stages, Naysmith envisioned Tide Lines as “an inspirational story of self-transformation, chronicling an adventure so many people would probably love to take off on.”

By early 2007 it became clear that not living the dream was not an option for these purposeful voyagers, even when friends and family expressed concern.

“You should be getting married and having children, not sailing the high seas forever,” Hugh’s mother Caroline says in the film, recalling her initial reaction.

“It’s now or never,” Ryan says on screen, also noting that “somebody suggested we all go to a marriage counsellor” before the trio sailed off in close quarters from La Paz, Mexico.

Hunter, owner of Victoria’s studios, had joined the project by then as creative producer, as did Malysheff, the local cameraman and Gamut Productions owner.

Other notable local participants in the self-funded project include animator Chris Orchard and composer David Parfit.

During the surfing, sailing and ultimately educational voyage dubbed the OceanGybe Expedition that took them across three oceans to Hawaii and global hotspots including Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Guatemala, New Zealand, Kenya and Indonesia, the adventurers were shocked by the plastics pollution they found on every beach they came across.

Before they saw the worst of this, they had a harrowing adventure — having to outrun a hurricane near Hawaii, a sequence documented particularly well.

“In the last week we learned the meaning of terror,” one of the men, visibly shaken, says into the camera after Hurricane Cosme suddenly switched direction, missing them by 100 kilometres.

“They had to put their motor on and just go,” Naysmith recalled. “They were just seven days out. I think it really bonded them as a crew.”

Naysmith flew to Managua, took a bus to San Juan del Sur on Nicaragua’s Pacific Coast and joined them onboard for three weeks at one point, stopping in Guatamela for fuel.

“We had to do some sketchy bribery,” he recalled, laughing. “We got along great but when you’re on that boat, you realize there’s no place to go and you’re not going to make it if you fall apart.”

Hunter and Malysheff also met the sailors in San Diego to shoot footage, with Hunter reconnecting in Maui. She spent three weeks on board for the home stretch to Winter Harbour. Sequences in Tide Lines include plentiful shots of tropical beauty; footage of giant turtles that sadly ingest plastic, mistaking it for jellyfish; encounters with conservationists such as Julie Church, founder of Ocean Sole, which recycles thousands of flip-flops that wash ashore; and beach cleanups in places like the eastern side of the isolated Australian islands of Cocos Keeling where massive piles of plastics such as sandals, styrofoam and pop bottles routinely wash ashore from Indonesia.

They also pass the infamous Great Pacific Garbage Patch, a vortex in the central north Pacific Ocean the size of Alberta where ocean currents deposit swirling masses of sludge and garbage.

Interwoven into the environmental story is the human element, notably the crew dynamics, and the impact of the voyage on their romantic relationships.

“There are so many stories that could have been told, but I think we’ve told the most important ones,” says Naysmith, who eventually cut his initial edit — 36 hours — down to 95 minutes. Interviews with the trio before and after departure tell most of the story, interspersed with footage captured mostly at sea by the crew.

“I gave them a crash course in cinematography and audio and sent them on their way,” said Naysmith, who has since forgiven them for sending back dozens of tapes damaged from salt corrosion.

Tide Lines will be re-screened Saturday at noon at the Vic.