There’s still a week of construction left on the latest round of safety upgrades for the Malahat highway. But already the big question is: So, what’s next?

What should we do with a stretch of highway so many Vancouver Island residents fear and loathe?

And is it worth dumping millions of dollars more into safety upgrades on a 55-year-old highway that could be rebuilt?

The long-term future of the primary link between Greater Victoria and the rest of the Island is up for debate, as part of a Ministry of Transportation study promised by the B.C. Liberals during its re-election campaign.

----------------------------------------------

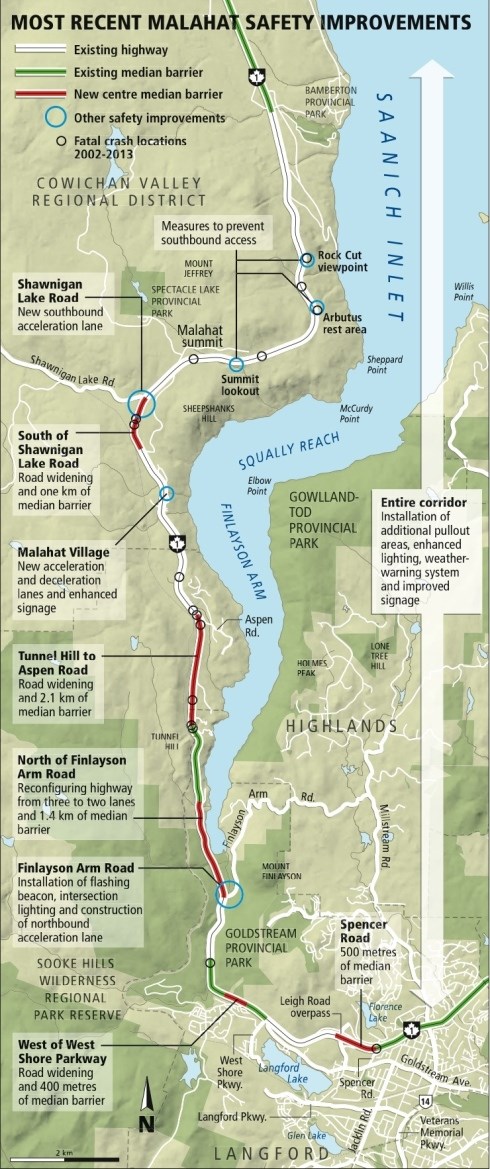

Scroll down for graphic of recent

improvements to Malahat Highway

----------------------------------------------

“It’s time to step back and look at all the transportation priorities at Vancouver Island from a more integrated perspective,” Todd Stone, the new transportation minister, told the Times Colonist.

“The Malahat is obviously a big piece of that. But there’s a huge part of the Island beyond the Malahat as well.”

The new asphalt has barely dried on the $8-million improvements. Drivers are still wrestling with construction, which has left traffic snarled for hours on some days. Work is expected to conclude July 20, weather permitting.

The upgrades started last July and added 5.4 kilometres of centre-line concrete barriers in some of the worst parts of the highway. Roughly 40 per cent of the 20-kilometre road is now divided.

Acceleration and deceleration lanes were also built at the Shawnigan Lake Road and Malahat village intersections, to improve traffic flow.

The safety improvements have earned praise from police and fire crews — as well as the families of those who have died in crashes on the highway — who say the medians will prevent death and serious injuries by blocking vehicles from veering into oncoming traffic.

Something has to be done to address head-on collisions, firefighters say

“I’m definitely happy with the upgrades,” said Rob Patterson, chief of the Malahat volunteer fire department, who is often first on the scene to handle the worst crashes on the road.

Much of the credit for the improvements goes to then-transportation minister Blair Lekstrom, who, after a series of fatalities in 2011, personally championed the upgrades.

Lekstrom drove the highway with local NDP MLA John Horgan to hear suggestions. He also met with families of those who had died on the road. “It was clear something had to be done,” said Lekstrom, now retired, in an interview.

The Malahat may have its twists and turns, but it’s not unique in its geographic challenges, said Lekstrom, who lives in Dawson Creek. “The highway is a pretty solid highway,” he said. “The uniqueness is how busy it’s become.”

When he announced the upgrades, Lekstrom was clear: Adding median barriers to the rest of the Malahat would be costly, complicated and require “some pretty significant rebuilds” of the old road.

Much of the highway is squeezed between sheer rock walls on one side and cliffs on the other. To accommodate centre-line dividers, the road needs to be widened at least 2.6 metres. That would require blasting out the rocks, or building over the drop-offs.

At the Malahat village site, for example, the addition of acceleration and deceleration lanes used up all of the provincial right-of-way between private businesses on both sides of the road. There’s no room left for medians without incurring significant expense, the government says.

Nonetheless, something has to be done to prevent head-on collisions there, say Malahat firefighters.

“It’s always been a real wonder for me how we haven’t had more people killed at that juncture,” said chief Patterson.

“It’s horrible. I’d like to see that [stretch] completely divided, but I don’t think that’s going to happen just yet.”

Government won’t reveal cost to install medians

Provincial engineers have calculated how much it would cost to install medians on the remaining 12 kilometres of the highway without the barriers, but the government has refused to make the figure public. It’s likely tens, if not hundreds, of millions of dollars.

The government remains hesitant to commit to such an expensive project.

“Installing median barrier[s] throughout the entire Malahat corridor is not practical in the short term,” says a 2012 ministerial briefing note obtained under the Freedom of Information Act.

Instead, the Transportation Ministry has dispatched engineers to analyze the stretch between the now-upgraded Shawnigan Lake intersection and the Malahat summit, the ministry said in a statement.

Locals call it “Nascar corner” because some northbound drivers try to speed past slower vehicles before the two lanes merge at the top of the mountain.

The 2.3-kilometre section would “require extensive widening” to accommodate a barrier, the government said, noting the engineering work would include a cost estimate, “which will help us understand the costs associated with these more difficult sections.”

Nascar corner should be a top priority, said Patterson, who lives nearby.

Three people died in a head-on crash there last October, one of the worst Patterson has seen. At the time, he told media of hearing the sounds of an explosion and children screaming, then finding bodies lying on the highway. Vehicles were still trying to drive by.

Many in the community simply want the government to pay for centre-line dividers.

“We’re going to have to blow up some rocks,” said MLA Horgan, whose riding encompasses the lower half of the highway.

Horgan pointed to the $600 million the government spent to improve safety and capacity along the winding Sea to Sky Highway between Horseshoe Bay and Whistler. “If you can make a roadway and transportation network like that one, on the Lower Mainland, in that terrain on the heart of the coastal mountains, certainly with ingenuity you can make those improvements on the Malahat.”

Dividing the entire Malahat would improve safety, but do little to address congestion on the road.

Roughly 22,300 vehicles travel the highway every day. The Malahat’s capacity is about 1,400 vehicles an hour, the government estimates. Above that, traffic bottlenecks.

Traffic came close last year — 1,323 vehicles an hour on the busiest day. By 2026, it could be as high as 2,500 vehicles an hour, though the government says that growth projection has dwindled due to the recent recession.

Study on road’s future languished when recession hit

Any plan to accommodate more drivers on the Malahat would depend on the provincial government’s long-term blueprint for the highway.

Currently, it has none.

A comprehensive 2007 study by engineering firm Stantec looked into the future of the road and gave the government a host of options: widen the existing route, build a new highway to the west, construct a bridge over the Saanich peninsula, increase ferry service, add commuter rail to the E&N line and bolster rapid-transit bus service.

But the study languished when the recession hit. Then came a provincial election, the botched harmonized sales tax, the fall of premier Gordon Campbell, the rise of current Premier Christy Clark, new ministers, new priorities and another provincial election on May 14.

Still, Transportation Ministry staff seem to be pushing for a long-term vision.

“The ministry would be well served to demonstrate that we are committed to continuous improvement that works towards a defined long-term strategy,” wrote David Edgar, a transportation planning engineer, in a Jan. 2, 2012, Malahat report, also obtained by FOI.

Historically, the ministry had assumed the Malahat would one day be upgraded to four lanes, Edgar wrote in a discussion paper later that month. He suggested upgrading the highway to three lanes, with medians.

The idea of rebuilding the road was shuffled aside.

“At this time, it appears unlikely the ministry will build an entirely new route ... for two reasons; one is the environmental issues of going with a new route through Goldstream Park and the second is the significant capital investment that can not be phased but must be made in a lump sum,” Edgar wrote.

Carving a new route for the Malahat looks easy on paper, but is fraught with environmental and logistical hazards, according to the 2007 Stantec report.

The cheapest option is widening the existing highway, Stantec wrote, with a price tag of $200 million to $250 million.

New routes fraught with environmental and logistical hazards, report says

Widening and slightly realigning the existing road would likely require tunnels and new bridges, and cost up to $400 million, the report concluded.

As an alternative, some have pointed to the E&N rail line, which runs parallel to the highway and sits mostly unused after the idea of restarting commuter rail service stalled.

Horgan suggested it could become a dedicated high-occupancy-vehicle corridor.

But the E&N route is twisty, and any road there would likely have a speed limit of 65 km/h, Stantec said in its study.

The two most realistic Malahat replacements would be new roads, built to modern safety standards, west of the existing highway.

One $400-million proposal follows an abandoned forestry road called Niagara Main, but cuts through 30 hectares of Sooke Hills Wilderness Regional Park, home to sensitive habitats and endangered species such as the marbled murrelet.

It also plows through the buffer zone to the region’s watershed. The Capital Regional District would be “very concerned about protecting the water supply” if a highway went nearby, said Ted Robbins, the CRD’s general manager of integrated water services.

An alternative $350-million route would bypass the Sooke parkland, but require 20 hectares of Goldstream Provincial Park.

“It’s not cheap,” Horgan said. “And how close do you get to the Sooke reservoir? That’s where the time is saved. I think we’d have a whole lot of debate on that, before we make decisions.

“I would suggest, in that context, it seems to me we have a route that is historic, workable, and we can start chipping away at the mountains or cantilevering over the cliffs to make that four lanes … with median barriers and acceleration/deceleration lanes.”

Alternatively, you could build a bridge to bypass the Malahat entirely.

To get a sense of the scope of that proposal, consider that a Saanich Peninsula-Mill Bay bridge would be four kilometres in length — almost twice the length of the new Port Mann Bridge in Vancouver. That project cost $3.3 billion, including highway improvements. Small vehicles pay a $3 toll per crossing.

Frustrated, some drivers have turned to the ferry route between Brentwood Bay and Mill Bay to avoid the Malahat.

Ridership is up 31 per cent in the last month, and anecdotal evidence suggests that’s from passengers trying to avoid Malahat construction delays, said B.C. Ferries spokeswoman Deborah Marshall.

But the route lost $1 million last year, and only moves 44 cars an hour. Even the largest vessel in the fleet, which wouldn’t be appropriate for the route, could handle only 410 cars. That’s a small slice of the Malahat’s hourly traffic.

B.C. Ferries isn’t considering increased service to compensate for Malahat traffic, Marshall said.

One argument the B.C. government has used in sidestepping a Malahat megaproject is that the road is no more dangerous, or crash-prone, than comparable highways.

On average, there are 53 crashes each year on the Malahat, the government estimates. Between 1995 and 2013, 29 people died in accidents on the road.

The collision rate is similar to other B.C. highways, but the “collision severity rate” is higher than the provincial average. Crashes close the Malahat twice as often as they do for other highways its size.

Almost every stretch of the road exceeds either the collision or severity rate, according to a February 2012 ministry email.

Head-on crashes aren’t the most common, but they are the most serious and have “a one in seven chance of the result being a fatality,” says a Nov. 17, 2011, internal report titled Malahat Safety Review.

Police suggested a dedicated Malahat traffic squad after a focused enforcement campaign by the Capital Region Integrated Road Safety Unit drove the fatality rate down to zero in the summer of 2011.

But neither the provincial government nor local police agencies have stepped up with the required funds.

One alternative is placing manned speed cameras in hard-to-enforce parts of the Malahat, said Sgt. Frank Wright, IRSU commander.

“I’m confidently optimistic we may be chosen to do the pilot project,” Wright said.

The Justice Ministry was quick to shoot down the idea, however, telling the Times Colonist that it was not considering speed cameras.

Lowering the Malahat’s 80 km/h speed limit also appears to be a non-starter.

“You say 60 [km/h] on the Malahat, but who is going to go 60? We don’t have the resources to enforce that speed limit, and people wouldn’t stand for it,” said RCMP Insp. Al Ramey, who runs traffic services on Vancouver Island.

The RCMP has jurisdiction over most of the Malahat, and believes any extra officers should be assigned on the basis of need.

“If someone said, ‘Hey Al, here’s an extra five guys, where would you put them?’ Well, you know what, I don’t think I’d put them on the Malahat,” Ramey said.

Officially, the new transportation minister says it’s too early to tell the future of the controversial highway.

“I don’t want to speculate on what further improvements might look like on the Malahat, or if alternative routes need to be considered,” said Stone, adding the government must work within existing fiscal constraints.

“But I’m confident that once I have a compete picture of the improvements we’ve made up to this point, what are the remaining highest priority areas on the Malahat, as well as the rest of the Island, we’ll have something to announce in the near future in terms of what this consultation process is going to look like.”

Meanwhile, advocates like the Malahat fire chief continue to push for action.

“I don’t know what the magic answer is,” Patterson said. “The focus is not to stop the rest of the accidents, because that’s not going to happen. What’s going to happen is we’re just taking some of the more horrific crashes out of the equation.”

----------------------------------------------

>>> Click here to download a PDF graphic showing future projects for the Malahat