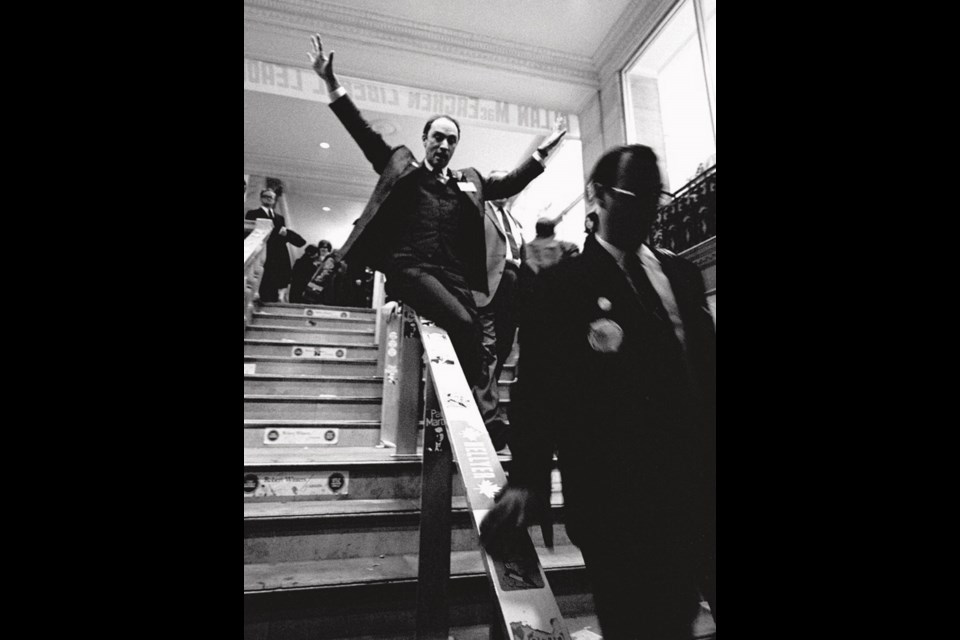

Some might not recognize the name. But we Canadians know the photographs. Especially that picture.

The photo in question shows Pierre Trudeau sliding down a banister at the Liberal leadership convention in 1968. He’s flanked by men in suits and ties. Trudeau, himself wearing a three-piece suit, is captured in mid-flight, his upraised arms forming a V.

The famous image is on the cover of Ted Grant: Sixty Years of Legendary Photojournalism. The 224-page book, set for release next week, is published by Heritage House, with text by Thelma Fayle.

Recently Grant, 85, chatted at his Gordon Head home about his life as a photojournalist. On the front door is a small sign that says: “An old crab lives here.” He says it’s to ward off door-to-door solicitors. In fact, Grant is friendly and nimble-minded, equipped with the kind of memory that attaches exact dates to key events.

The Trudeau photo exemplifies the way he operates as a photographer. Grant is a “from-the-gut” shooter. He reacted in a split second, shooting immediately and asking questions later.

“My whole method has been, ‘Geez, look at that — click!’ Just as fast as that, sometimes. That’s how you get that Trudeau picture.”

On that day 45 years ago, Grant joined the press corps gathered at Ottawa’s Chateau Laurier Hotel. Trudeau was running to succeed Lester Pearson as Liberal party leader. The other journalists had already left the hotel when Grant detected a ripple of laughter behind him. Swivelling around, he saw Trudeau puckishly embarking on his descent.

“I went, ‘Oh geez!’ Camera went up. I went click. I got two more frames away. And then I had to run myself because he was comin’ right down on top of me,” he said.

He didn’t know what he had until later, when he developed the film. Grant was jubilant when he saw the photograph, which he knew was an exclusive.

“I thought, ‘Oh my heavens, I can’t believe I got that!’ And part of it was, I knew I had to be the only guy.”

Grant is regarded as one of Canada’s greatest photographers. In 1999, he and Yousuf Karsh were presented with lifetime achievement awards by the Canadian Association of Photographers and Illustrators in Communication. More than 280,000 of his images, representing a 60-year career, are collected in the National Archives of Canada — the largest such archive for a Canadian photographer.

His assignments include bullfighting in Spain, the Vietnam War, children affected by the 1986 nuclear accident in Chernobyl and the twilight days of right-to-die campaigner Sue Rodriguez. Grant has photographed newborn babies, rawhide-tough cowboys, nude 1960s scene-makers and aboriginal grandmothers.

One of his classics is a perfectly timed photograph of sprinter Ben Johnson, forefinger pointed heavenwards in victory at the finish line as he won a gold medal at the 1988 Seoul Olympics (Johnson was later disqualified for doping). Determined to get a great photo, Grant arrived at 7:30 a.m. to secure a prime spot. Other photographers tried to elbow him out of the way. But Grant, holding his own for hours, wasn’t having any of it.

And then he got his shot. The shot.

It was an emotional moment for the photographer, who says he’s such a proud Canadian “if you cut my finger I bleed red maple leaves.” Chuckling, Grant recalled: “I’m looking through a 400-mm lens, crying my eyes out, trying to focus.”

He has photographed his share of bigshots: Israeli prime minister David Ben-Gurion, prime minister John Diefenbaker, John Travolta, Jackie Onassis. Yet some would argue Grant’s most moving photographs are of ordinary folk.

On one assignment, he was directed to obtain photographs of newborn babies. So Grant contacted eight women reaching the end of their pregnancies. He instructed them to contact him before they went to the hospital to give birth. Grant kept his camera bag at the ready, right by his front door.

It didn’t work out as planned. Some were false pregnancies; for others, he arrived too late. When he described his dilemma to hospital staff, a doctor suggested Grant show up next Wednesday morning. That’s when he’d be inducing a number of pregnant women.

“By noon, I had shot six babies being born, one right after another. It was incredible,” he said.

One newborn appeared to be a “blue baby.” Grant was devastated. And then … a small miracle.

“All of a sudden, the little kid started hollering its head off. And it begins to change. It becomes pink and beautiful. You had those kinds of things.”

Advice for aspiring photographers? The most important thing when taking a photograph, Grant says, is how the subject is illuminated.

“Lighting is number one. That is the life of the photograph,” he said. “The light is the life and the content is the soul.”

Ted Grant and Thelma Fayle will speak and read at the Oct. 27 book launch for Ted Grant: Sixty Years of Legendary Journalism. The free event takes place 2 p.m. to 4 p.m. at the David Lam Auditorium at the University of Victoria.