The Centennial Era — what a watershed era for my family.

Growing up in mid-century times, our family concerns appeared to my young eyes and ears full of the lore of great ceremonial occasions — and events of the Centennial Era were tailored to deliver.

As a probing adolescent snooper, investigations revealed my grandfather’s busy collection of small domestic trophies featured memorabilia from the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific exhibition in Seattle — with chinaware depicting illustrations of elaborate pavilions, crowded parades, international folklore displays — and best for my developing sensibility — firework spectacles!

The pump was getting primed.

Being only about five at the time, I missed out on the first big centennial extravaganza in Victoria — the 1958 centenary of the creation of the Crown colony of British Columbia — but remember intriguing first hand accounts.

Celebrations were focused in the Inner Harbour, and my Auntie Emma, the postmaster’s secretary, had a ringside seat from her office in the old post office building — overlooking a busy regatta event that included a staged pirate’s battle.

Noted was an added contribution, in an early guerrilla urban landscape installation foray, the Junior Chamber of Commerce created the floral “Welcome to Victoria” inscription overlooking the basin.

Not long afterward, ceremonial events did more directly catch up with me — as, with my slightly older brother, Greg, we found ourselves scrubbed and tidied up, tousled hair slicked back, and decked-out uncomfortably in uncharacteristic new shirts, to join blocks of crowds thronged under an astonishing display of cherry blooms on May Street.

The purpose: to watch radiantly smiling and beautiful young Queen Elizabeth waving at each of us as she passed close-by in procession in a majestic convertible touring limousine. Enlisted performance in a series of cub-scout church choral concerts soon followed, again dressed up in unfamiliar formality.

We were scheduled for another session at Government House — but it burnt to the ground just in time. Instead, for some years we got to watch the completion of its reconstruction in view above the schoolyard at Sir James Douglas elementary — an unwavering image of imperious authority and ostentation beyond reach, overlooking our rounds of playground marble tournaments.

The ceremonial bug had bitten deep — word of ambitious civic initiatives filled both newspaper headlines and reports from my mother’s tinny old kitchen-counter radio — first the dedication of a bronze bust of the young Queen near our play area in Beacon Hill Park — then descriptions of a series of elaborate 100-year birthday plans for downtown Victoria.

But first an abrupt diversion: returning from a trip out of town, Auntie Emma and my grandmother Mabel gave enthusiastic account of a wonder of extravagance beyond imagining — the astonishing new World’s Fair in Seattle. Many photos of Mabel, placed variously in her new granny hat, in the midst of futuristic surroundings were provided.

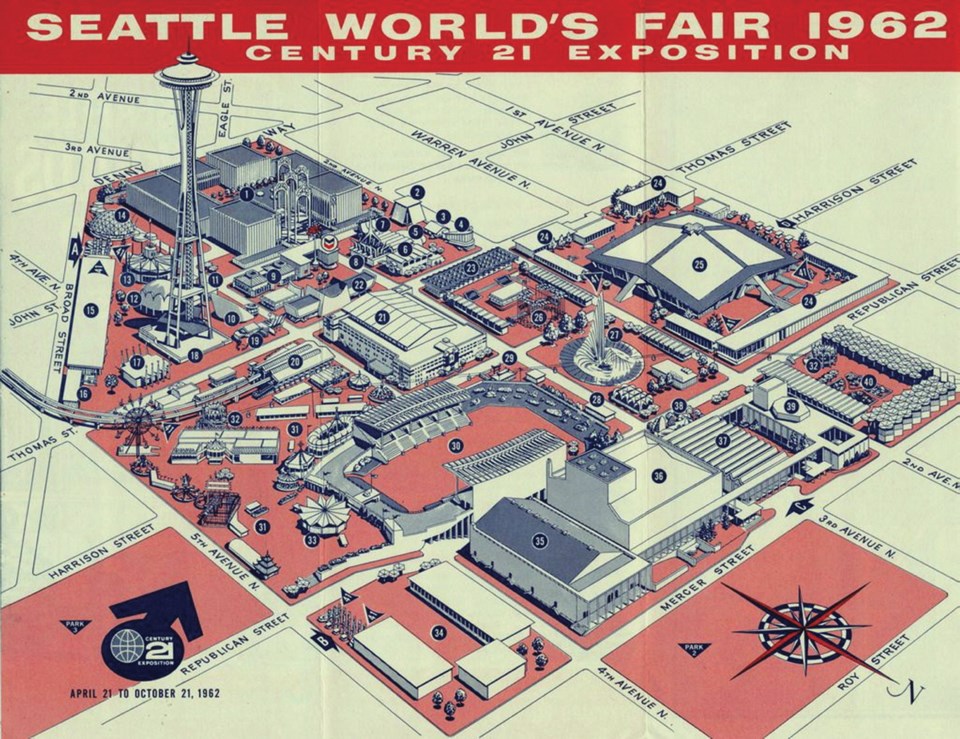

Arrangements were quickly made to include my brother and I in a summer boat trip to Seattle in the newly backyard-self-constructed boat of good friends of my parents. After the 25-foot plywood cabin-cruiser finished its bobbing passage through the mysterious forested scenery and huge tides of the San Juan Islands, passing the huge mechanical jaws of the Chiltern locks, and into a crazed tangle of recreational boats in Lake Union, the storied World’s Fair grounds suddenly sight swung into view.

I still can vividly recall the dazzling early-evening image across the lake: illuminated pavilions, helicopters weaving through searchlights, smoke and fireworks — and presiding above all, the floodlit Space Needle, topped with its gas-jet flame antenna.

In preparation, Greg and I had well-earned a tidy pocket budget by washing a series of uncle’s gargantuan 1950s’ cars and were anxious to hunt down the ultimate prize of this adventure — a large Space Needle pen. In the end, from sadness that my parents had missed the trip, I forewent my pen and instead bought a new $7 jet-age plastic counter radio as a gift for my mother.

After viewing many pavilions, futuristic experimental cars, an eight-foot stuffed polar bear, ascending the Space Needle, and an exciting monorail journey to downtown and back, our farewell included watching a futuristic water-ring variety show — including an elaborate horse rodeo dance centred on singing cowboy stars Roy Rogers and Dale Evans and their horse, Trigger. This was concurrently surrounded by an orchestrated series of three-level water-ski displays — and, of course, fireworks closed the show.

On our return home the excited spirit of the times continued. As a second-generation city native, my father was particularly attuned to progressive changes in Victoria, and our group of five lively children were taken on a continuing series of Sunday drives and family walks to review a series of unfolding centennial projects.

It was our good fortune to drive the new Ring Road at the University of Victoria as a quarter circle, a half circle, a three-quarter circle, and then the fulfilled destiny of a complete circle.

From his air force associations my father knew city urban planner Rod Clack, and he expressed appreciation on the degree of innovation underway in the city centre. As school groups we viewed intriguing models and the huge gaping excavation for the new provincial museum, and had visits to watch Centennial Square taking form. With my experimental photographer Auntie Emma, we undertook a summer evening foray to document the many illuminated effects of the new provincial centennial fountain, set south of the legislature.

School visits to developing Bastion Square were also undertaken, leading to attendance at a school band concert at one of the several staged openings of Centennial Square.

In the summer of 1966, new facilities at Royal Athletic Park were underway in a stage of reconstruction as another centennial project — and to observe that year’s provincial centennial of the union of the Vancouver Island, and mainland colonies —an evening music and theatrical celebration was mounted — we attended, heard speeches, watched historic stage panoplies, and were delighted and amazed with a tremendous mid-’60s culmination: oscillating coloured spotlights playing on a full brass and rock band, and a gaggle of dancers-of-the-day in full 1960s floral pop-fashions, enacting a series of stylish period dance and comedy performances.

As 1966 came to a close my parents made a startling family declaration: After years of domestic saving, a behemoth new family station wagon appeared filling the driveway, and the five were told of the up-coming ultimate family drive — a trip across the new Trans-Canada highway, to behold Centennial Canada, and to attend the already mythical national festival at Montreal — Expo 67.

My father topped the electric-metallic-blue 1967 Plymouth Fury II with his own similarly painted streamlined plywood roof-top carrier, loaded in the family camping-gear, and christened the highway liner, in a reference to his Second World War RCAF squadron, the Blue Goose.

Indeed, it had many features of a Lancaster bomber — including, to accommodate the five, a rear-facing pop-up seat — ideal for setting crosshairs on the overtaking approaches of the endless onslaught of other family campers and trailers that filled the Trans-Canada that summer.

Almost every vehicle somehow sported the new Canadian flag — ours moved around in locations in the car as my two sisters, Linda and Loralee, and small brother Paul continuously negotiated improved seating arrangements.

For many of our fellow transcontinentals, family camping was a collective village on the move, as we shared campsites along a string of new city, provincial and national parks. Notable was our night in Golden’s riverside campsite. The canvas tent was set up, leaky air mattresses hopelessly puffed full, and thin sleeping bags rolled out, as our folks bade us goodnight, and retired to their foam mattress luxury in the Blue Goose.

With darkness, from throughout the Columbia River Valley a thick cloud of mosquitoes concentrated itself forcefully on our own campsite. My parents were awakened before dawn as my older brother led the hopping five-voice plea for the sole bottle of the repellent lotion Deter, positioned under the Canadian flag, behind the locked doors of the station wagon.

Town after town we visited Dad’s many old air force mates, toured the new civic projects that seemed to be underway everywhere under new Canadian flags — we were aware that we were witnessing a form of re-birth and renewal of a great young nation. My mother took over a few days at the wheel, piloting the jovial Blue Goose quest for campsites on a convenient shortcut side-trip through the middle of Detroit, then in full protest-riot mode.

The visit with Dad’s bomber captain in Toronto was inspiring — featuring a tour of the soaring new Toronto-Dominion bank tower and the science museum. But, of course, the ultimate centennial payoff was in Montreal.

Bivouac secured in a field just south of the St. Lawrence River, we took the new subway into town, toured a stunningly beautiful metropolis in a golden open-top tour-bus operated by a garrulous gold-suited guide — who to this day remains a living urban oracle for my sister Linda. We wondered at the city vista from Mount Royal, which included a beaconing view of the magic Expo site distant on its islands over in the St. Lawrence.

The several days of visits to Expo 67 were a wondrous apex — dizzying for a small city family. Surging crowds of all ages; displays and representative performances of nations from around the world; colourful fashions, multi-media expositions; every imaginable mode of transportation; boats, canals, aerial tramways, and highly futuristic design and architecture on all sides.

Overall — truly a vision of a idealistic vision of a world of harmonious multicultural humanism and creativity.

Like many Canadian families of the time, even to this day my brothers and sisters talk of our experiences in the Centennial era: what lasting memories. — Chris Gower