MINNEAPOLIS — From the time Steve Anderson was 12, his relationship with his father had no warmth, just a slow burn.

William Cope Moyers spent decades with his famous father’s stature as a “self-imposed burden” on the road to addiction.

These two sons have travelled different paths with their fathers, but each found reconciliation where there once was alienation.

Fathers and their male offspring have found themselves at odds since Abraham offered up Isaac for sacrifice. Divorce, disaffection and drugs can be a cause of such disputes. But almost any difference can be exacerbated by a common father-son dynamic: letting things go unsaid.

“In the past, Mom was the one they went to for emotional issues.” said Mindy Mitnick, an Edina, Minn., psychologist. “Moms often are about the feelings in the family, and dads are about the work in the family.”

While times have changed, men who came of age in the mid-part of the 20th century have a well-deserved reputation for holding back emotionally. As Mitnick points out, “boys learn a lot about how to be a man in the world from their fathers.”

So a cycle of estrangement often continues.

“I didn’t know how my dad felt about things,” said Minnetonka therapist John Reardon. “I knew when he was angry, but underneath I didn’t know what was going on. And so you say, ‘I’m never gonna be like him,’ and then you get down the road and [realize] I sound just like my dad.”

But that cycle can be broken.

Anderson and his father, Bill, are now close, having gone from seeing each other once or twice a year to planning a weeklong trip to Yellowstone this summer. But growing up, “he wasn’t around much” physically or emotionally, said Steve Anderson, 42.

“As soon as I left home, I thought, ‘problem solved.’ ”

Still, for years, Steve Anderson would broach the breach between them, to no avail. “When I tried to bring up how I felt,” he said, “my dad would get defensive and talk about how his dad died when he was five. And while that’s true, who cares? I need you to own up to what happened with us.”

This is a common scenario, said William Doherty, a University of Minnesota psychology professor. “In general, father-son relationships are the least ‘talky’ family relationship, which can make them less volatile … but can also make them go through long estrangements when things have gone sour, because they can tolerate the distance and don’t necessarily have the skills in talking through the estrangement and reconciling.”

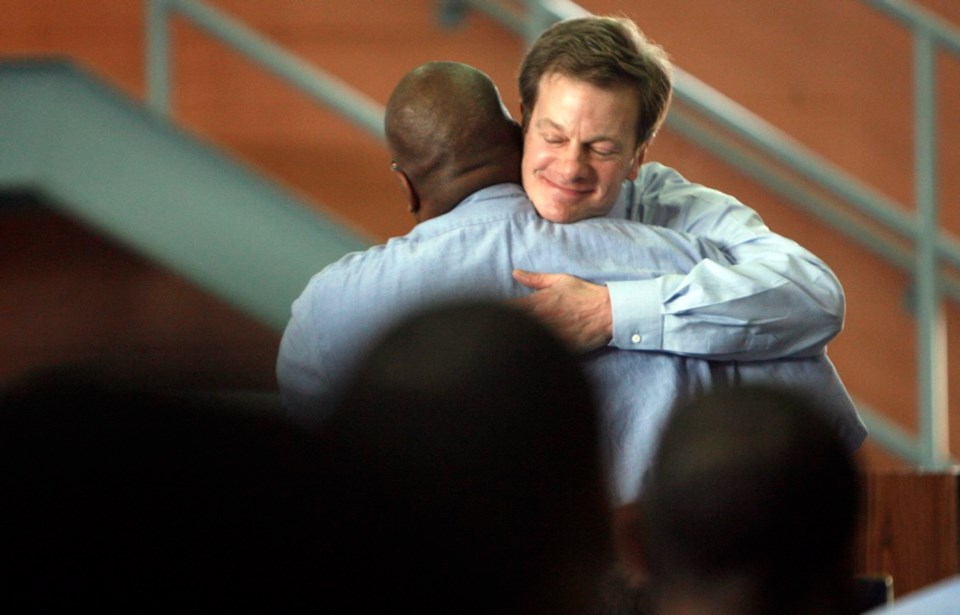

The two men worked their way out of the schism. Steve gained great insight during a weekend with a support group fostering healthy men and families. At about the same time, his father came to a realization: “I had always been defensive,” said Bill Anderson, of Moline, Ill. “I was involved with a 12-step group, and part of that is making amends to people we have harmed. That also helped me learn to express myself.”

A short while later, the two men were together “and for the first time in my life,” Bill said, “I told him, ‘I’m really, really sorry for the way I acted.’ I think some tears were shed.”

William Moyers’s father, Bill, was present throughout his childhood even though he had a busy work schedule: White House press secretary, Newsday publisher, TV correspondent.

William strived to have as accomplished a career as his dad. That self-imposed pressure led him to years of substance abuse and eventually to a crack house in Harlem. But he didn’t hit rock bottom until 1994, when he was working for CNN in Atlanta. By then, he was a father himself.

“My father sees me as an addictive father — I’ve got two baby boys at home and I’m drunk and stoned again — and in that moment he said, ‘I hate you,’ ” Moyers, 54, said. “And of course I answered ‘I hate me, too.’ The hate was nothing more than fear cloaked in desperation for both of us. So the veneer came off our family.

“I think fathers can be convenient whipping posts or antagonists when we, as men, are struggling with our own shortcomings.”

The subsequent rehab stint found Moyers delving deeply into his relationship with his father. Two years later, he came to work at Hazelden addiction-treatment centre in Center City, Minn., where he is now vice-president of public affairs. Bill Moyers and his wife, Judith, wrote the foreword to William’s book Now What? An Insider’s Guide to Addiction and Recovery.

“I’m a fortunate son, a lucky man because I did get a chance to … make amends to my father by living my life to the best of my human ability.”