“If I were Luke Skywalker, I would deny my destiny to rule the galaxy,” the writer of this love letter proclaims, then goes on to promise his beloved to forgo immortality with Arwen (a Tolkien character) and tell the Exiles (from The Matrix) that he cannot be their saviour.

You get the idea.

“I married him anyway,” said the recipient, Kelly Donohue, of Jonathan Babu, now both 41 and the parents of two children.

Their love letters, added Donohue, of Gaithersburg, Maryland, have morphed from science fiction to domestic, such as Babu’s “My love for you is like when the children sleep before 10 p.m. and after 6:30 a.m. and no one is constipated.” Now, the letters are more often digital than handwritten as the couple juggles their law practices and gigs for their kindie band, Here Comes Trouble. Together, the letters chronicle their courtship and marriage.

Love letters matter — whether or not the writers become lifelong partners, said Michelle Janning, professor of sociology at Whitman College in Walla Walla, Washington.

“They represent who we were, which is part of who we are,” Janning said. “They become our relationship counsellors, reminding us of what to avoid in future relationships and what to rekindle.”

It’s no wonder 88 percent of people save their old love letters, according to Janning’s 2014 national study, “Love Letters Lost? Gender and the Preservation of Digital and Paper Communication From Romantic Relationships.”

The more than 800 participants ranged in age from 18 to 89.

“He turned out to be a dirtbag,” said one participant, but she kept her former love’s letters anyway, because, she reported, “they tell me how wonderful I am.”

Others said their love-letter exchanges serve as journals that help them reflect on their relationships, past and present. One participant said they remind her of “how my thoughts have changed — or not.”

Women are more likely to save love letters than are men, said Janning, who said this supports the theory that women are usually the family’s “kinship keepers.” Yet men revisit their letters more often.

“Men are also more likely to keep them in visible places, like their bulletin boards or on top of their dressers,” said Janning.

“We could interpret that as keeping trophies or as being more sentimental.”

While both genders write and keep love letters, “men pour their hearts out,” said Janet Gallin of San Francisco, who hosts the Love Letters Live radio show and conducts letter-writing workshops.

For the shy writer, Gallin advised, “address the envelope and put on a stamp first, so it will get done. Pick at least one thing you like about her. Embellish the envelope, which is like the gift-wrap for the letter. Women, put a lipstick kiss on it.”

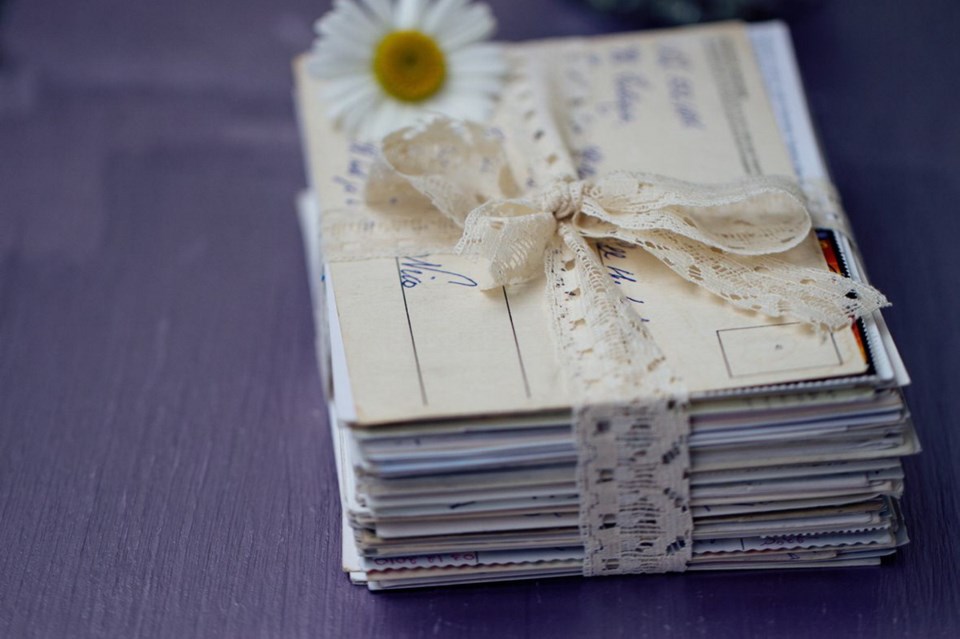

The love letter should be handwritten, agreed Gallin and Janning, whose study participants considered paper versions “more thoughtful and personal.”

Both genders said they save more paper than digital letters.

“The handwriting itself has meaning,” said Babu.

If for no other reason, said Gallin, tuck away your love letters to entertain your children after you’re gone.

“People tell me when they’re taking apart a family home and grieving, their parents’ love letters are glorious hellos from regions unknown,” said Gallin.

Janning’s study will be published in the 2015 book Family Communication in an Age of Digital and Social Media, edited by Carol J. Bruess.