Mark Tobey/Teng Baiye

Mark Tobey/Teng Baiye

Jo-Anne Birnie Danzker, ed., Frye Art Museum, Seattle, 2014, 80 pp.

Mark Tobey (1890-1976) was an artist of Seattle, a West Coast mystic in 20th-century art. And he played a significant role in Victoria’s art life.

Emily Carr invited him up to teach a “masterclass” in her studio in Victoria in 1928. Just then, Tobey was enjoying the friendship of a Chinese artist, Teng Baiye (1900-1980), who was studying sculpture at the University of Washington.

During 1927 and 1928, Tobey studied calligraphy with Teng, and formed a deep personal friendship. In 1934, Tobey visited Teng in Shanghai and in response created his “white writing” painting style, indebted to his study of Chinese calligraphy and ink painting.

Later, arriving on the international scene at the same time as Jackson Pollock, Tobey’s “calligraphic” style brought him recognition, and he won first prize in the Venice Biennale of 1958.

Tobey also enjoyed escaping to sleepy Victoria, where he befriended art gallery director Colin Graham. Tobey showed here, and encouraged his Seattle art collectors to give their artworks to Victoria. His “white writing” technique later inspired Jack Wise, who carried this teaching to another generation of artists.

It was not easy trying to discover what became of Teng’s paintings after the Cultural Revolution. The text focuses on Teng, but the excellent reproductions in this beautifully designed volume are mostly of Tobey’s paintings, and they are first rate.

A Sublime Vernacular: The Landscape Paintings of Levine Flexhaug

By Nancy Tousley and Peter White, Art Gallery of Grande Prairie, Grande Prairie, Alta., and Figure.1 Publishing, 2015, 160 pp.

Levine Flexhaug (1918-1974) was a celebrity back home in Climax, Sask., and points west. He was a “speed painter,” who set up his easel in the window of Gryde’s Hardware and General Merchandise, or in the parking lot of a provincial park. And, before the eyes of passersby, he’d knock out a batch of generic romantic landscapes, six or eight at a time. Real oil paintings, in real frames. Sell ’em for a dollar or two.

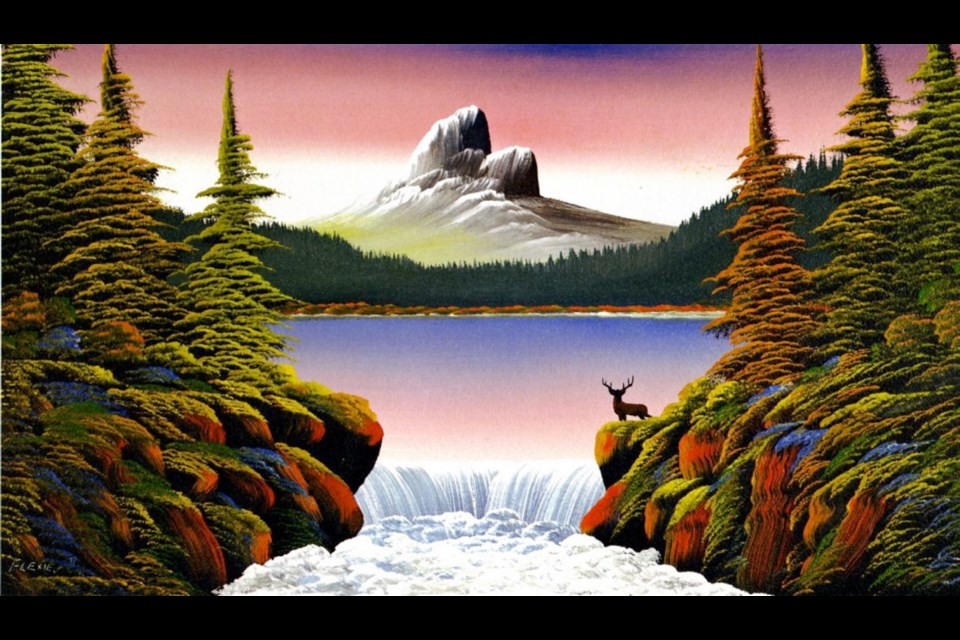

You’d recognize a Flexhaug painting if you saw one: view of mountain peak seen over a lake, framed by two pines, with stag (optional) raising its antlers in silhouette in the foreground. Sometimes a waterfall.

In his heyday, between 1937 and 1967, Flexhaug worked the crowds, just like the guys on TV — Jon Gnagy Learn to Draw, or that celebrity painter Bob Ross. He could paint a snowy peak with a single swipe of his brush. Though Flexhaug never made it to TV, by the sheer number of his productions he might have been the Prairies’ most popular painter.

At first I suspected a parody. Could these writers be serious, giving Flexhaug the whole museological treatment with chapters on “Flexhaug in Context” or “Flexhaug and Landscape Theory”? This book has biography, analysis and 119 full-colour reproductions of his simplistic paintings, which reminded Prairie folk of everything their Prairie home wasn’t.

Two-page spreads are crowded with as many as 18 vividly coloured paintings, each with a startling sameness. Their similarity is only superceded by their banality.

Am I missing something? Is this a joke? The collectors, the curators and writers, gallery directors and publishers seem to take the artist seriously. Aside from the paintings, “Flexie,” as some people called him, gave these writers a pretext to write a social history of Prairie life away from the city.

But that can’t make up for the pages given to lurid colour plates of cheap, repetitive and eventually unsatisfying paintings. There are so many other stories of Canadian art history waiting to be told.

Anna Banana: 45 Years of Fooling Around with A. Banana

Michelle Jacques, ed., Art Gallery of Greater Victoria and Figure.1 Publishing, Vancouver, 2015, 160 pp.

The publisher who brought us Flexhaug’s Sublime Vernacular has also delivered a sunshine-yellow volume with a lot of white pages inside, titled — inevitably — Anna Banana.

In case you haven’t heard, Victoria is about to go bananas when this mail/performance/conceptual artist’s retrospective opens in two places, at the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria (Friday, Sept. 18) and Open Space (Saturday, Sept. 19). Long after her show is passed, this book will be shining out from bookshelves, inviting us with an unusually attractive design (credit Jessica Sullivan from Figure.1 Publishing, Vancouver).

By a sort of cultural algebra, Anna Banana has removed Art from every equation and substituted a banana. Michelle Jacques, chief curator of the (newly renamed) Banana Gallery of Greater Victoria, has made sense of the entire Encyclopedia Banana, and offers an extensive and thoughtful text describing 45 Years of Fooling Around with A. Banana.

Anna Banana was born in Victoria, as Anne Long. She appointed herself Town Fool here in 1971 and, at a time when other artists took names such as Mr. Peanut, Art Rat, Dr. and Lady Brute, she became Anna Banana. Artists were then turning away from the gallery system, and began to correspond by mail — postcards, for heaven's sake. Through the Image Bank Request List she made contacts that have taken her all over the world.

Ever since, she has created, printed, sent, received and performed things on a banana theme. Banana makes her own costumes and envelopes, posters and newsletters. With her antique pinhole perforator machine, she prints and issues her own stamps. This is art without commerce, made to elicit a positive response.

All artists should have a book about them. This, definitively, is Anna Banana’s.