Calgary took me by surprise. There is public art everywhere in the city.

Calgary took me by surprise. There is public art everywhere in the city.

The sidewalk beneath my feet was patterned with concrete etched in patterns of fallen leaves, in smooth and pebbled texture. In the forecourts of every corporate tower, large sculptures engage the esthetic aspirations of the citizens. There is statuary to be found around every corner: realistic bronze bison, impressionistic horses made of repurposed farm equipment, giant abstracted nuts and bolts in primary colours by Sorel Etrog.

The larger landscapes are punctuated with giant images, such as a 15-metre-tall human head made of a network of stainless steel wires, or the giant blue circle poised in the distance, surmounted by a double lamp standard.

The artfulness of it all goes further than sculpture. The city is positioned at the confluence of two rivers, the Bow and the Elbow, and crossing them are many bridges. The old iron bridge in the east is now illuminated with an engaging light show of colours.

In the west, the 2012 Peace Bridge, a pedestrian and bike crossing, was recently commissioned from Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava. He’s world-famous for the breathtaking amenities he has created for cities with aspirations, and for Calgary he designed a beautiful double-helix tubular truss that elegantly surrounds a walkway covered with a glass roof.

The city’s leading museum and art gallery, the Glenbow, was celebrating its 50th anniversary, and admission was just 50 cents. Inside was a display of 50 “greatest hits” from the collection.

Some have to do with the history of Canada: Frances Ann Hopkins, Emily Carr, David Milne. More are concerned with the story of Alberta: Marion Nichol, Walter Phillips, Chris Cran. First Nations have their own galleries, and nearby is an outstanding collection of wood and stone sculptures from India, Tibet, China and Japan, donated by Bumper Development Corp. Upstairs are interconnecting rooms with mineral samples, crystals of every shape and colour.

Some of the commercial galleries in Calgary offer Group of Seven landscapes, and cowboys and Indians in bronze. Others present the legacy of the Emma Lake Workshops: colour field abstractions suitable for the largest walls. The Loch Gallery got my undivided attention with an exhibition (both on loan and for sale) of about 40 paintings by William Kurelek (1927-1977), Canada’s great narrative painter. Alberta is a great place to consider this “prairie boy’s winter.”

Though Calgary could be a barren and cold mini-metropolis, art makes a difference. It’s not just an ornament there, but a civic expectation.

The Natalie Brettschneider Archive, a project by Carol Sawyer, has just opened at the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria (until Jan. 8). It looks, on the surface, to be a typical gallery show of paintings and photos by a variety of artists from a single period. They are all artists of local interest from a former time except one: The main character has existed only in the mind of Carol Sawyer.

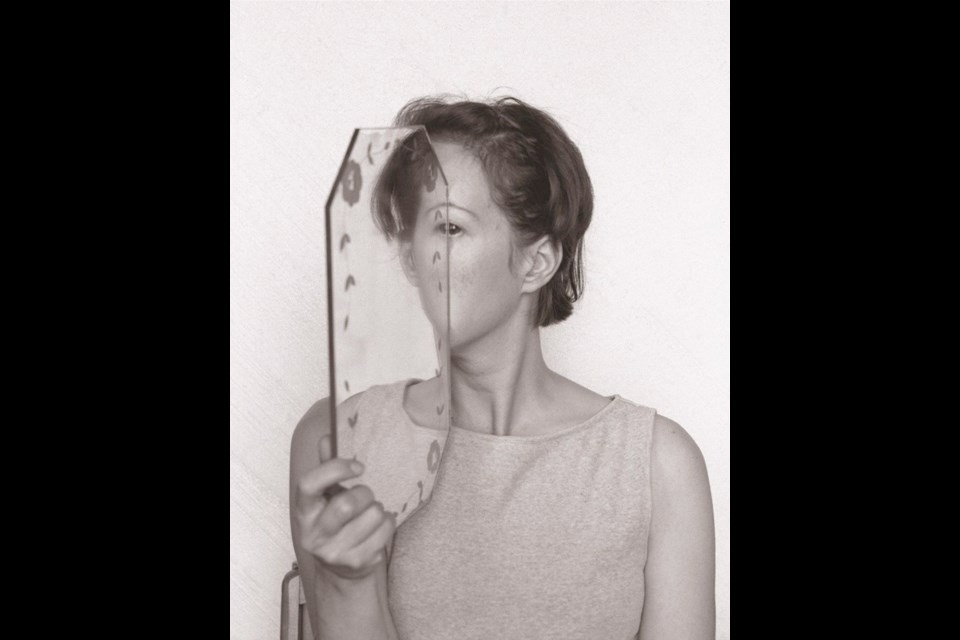

Sawyer’s fictional personage, Natalie Brettschneider, is presented to us by the use of faux-archival materials. Among other pseudo-ephemera, Sawyer has made toned photographs printed on antique papers, showing Brettschneider enacting an amusing series of Dada interventions.

Channelling the mood of a bygone era (circa 1920-1950), the imaginary artist adds tumbleweed headdresses to her period costumes, poses for imaginary magazines, and looks out of eyeholes poked through giant leaves. Sawyer can really make us believe that Brettschneider is a formerly unknown Canadian avant-garde artist. Her fond look back at an imagined art world is created with considerable skill and humour, and should be allowed to stand on its own.

The other half of the show, assembled by Sawyer, offers a much-needed look into some all-but-forgotten women of local art history. Working largely with the collections of the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, she brings to light paintings by artists — mostly women — that the gallery collects but almost never shows.

You might have heard of Molly Lamb Bobak, and even Vera Weatherbie, but it has been a long wait for paintings by Irene Hoffar Reid, G.K. Ewan and Margaret Carter to be brought up from the vaults. Amplifying the context of these paintings are photographs from premier local photographers of the first half of the 20th century, including Harold Mortimer-Lamb, Harry Upperton Knight and Ken McAllister. All are worthy of art-historical attention.

By seamlessly intermixing the real artists and her imaginary character, Brettschneider, Sawyer has left an unanswered question at the centre of the project. A great deal of the story line for this show is carried by extensive text panels, yet as one reads one’s way through the exhibit, it is impossible to separate fact from fiction. Are Frances Barwick and Douglas Duncan real people? How did the fictional Brettschneider get a painting on her arm by the real Scottie Wilson?

Thus, both of the thoughtful and well-made parts are tainted with the annoying quality of historical fiction. What can we believe? I think of books I’ve read in which, for their own novelistic purposes, writers have subjected Emily Carr to electro-shock therapy (Be Quiet, by Margaret Hollingsworth) or invented a French Canadian lover for her (The Forest Lover, Susan Vreeland). The audience is amused, but might come away mistaking creative licence for what actually happened. Real but relatively unknown artists such as Virginia Ryan and Margaret Carter are in danger of becoming mere footnotes to the life of Natalie Brettschneider.

Think about it. And enjoy this room full of pictures. Sawyer encourages us to “remain open to the potential of the possible over the proven.”