Sylvia Taylor’s lyrical memoir of life as a rookie deckhand captures the thrill and the perils of commercial fishing in a bygone era. The excerpt below describes an early-season stopover in the bustling village of Port Hardy and offers a glimpse of hardships that would soon beset the industry in the form of depleted fish stocks, shortened seasons and the tightening grip of government regulation.

The Cauldron of the northern B.C. coast is just what the meteorologists’ name implies: a bubbling, primeval soup of massive tides; deadly reefs, shelves and pinnacles; torturous narrows; and open seas all the way north to Alaska and west to Japan. Frigid Bering Sea currents hurl themselves into the balmy south Pacific waters sweeping up from Japan and Mexico.

A combination of any of these at any time can explode into storms of epic proportions. Winds of 320 kilometres per hour have been clocked at Cape Scott at the northern tip of Vancouver Island — seas that would swallow a four-storey building.

Scientists from all over the world come to study this restless, unpredictable, untameable world that terrifies some and enchants others. It reminds us daily who is really in charge. It seduces us with gentle beauty, then explodes into terrifying rages. Some people can’t bear feeling so insignificant, and others find it a blessed relief. This is no place for control freaks and egotists, but it is just the right place for the wild hearts, the romantics and the eccentrics.

For most of us, it wasn’t just a way to make money or run from conformity; it was the call of the wild, the last great frontier of our great country that still rang with the ancient songs lodged deep in our bones. We were here to be part of something greater than the domesticated life of the urban treadmill and to continue the tradition of our courageous ancestors throughout history who had chosen the unknown over the safety of the mundane.

The Cauldron had gone from a simmer to a bubble overnight with a marine forecast for a bit of a boil by that night. The clanging of riggings and uneasy shifting of boats before first light dragged us from our beds to make the 22-mile run from Port McNeill to Port Hardy before things got nasty.

We slipped out of Port McNeill’s choppy bay, coffee and cigs firmly in hand, and into a mounting lump that signalled our first foray out of the sheltered Inside Passage into the relatively open waters of Broughton Strait. By Port Hardy, we would be full-on to the winds finally let loose and funnelling down the coast from Alaska. It kicked up fast and mean, so we ran full throttle with stabilizers up to squeeze out the Central Isle’s maxed-out running speed of eight knots.

We pulled into the relief of Hardy Bay about the time most people in the other world were sipping morning coffee in their pyjamas. I had been up for hours and had already rodeo-rode a rising gale and got my first dose of the frontier town of Port Hardy.

We wandered the commercial docks and waited for the electronics repair shop to open, hoping to get our pilot fixed that day while we were kept in port by the weather. Four days had slid by already, and without a pilot I would have to sit in the cabin all day steering the long, slow tacks back and forth on the fishing grounds while Paul worked the gear on deck.

I would do what needed to be done, but was restless to get out there in the stern and really fish. I wanted to do the real stuff: play with the boys, run with the big dogs, or the highliners in this case. There was nothing more demeaning than being referred to as a lowliner, someone who barely scratched out a living and had to struggle to make the dreaded mortgage payment and licence-renewal fees every year.

The glory days when a fisherman could take it easy over the winter and enjoy some down time would soon be over. Even though the trolling season ran from mid-April to the end of October, the first and last month were often just too unpredictable and rough with bad weather. But no one could have imagined the industry would be in such peril that by the mid-’90s the seasons would be down to eight weeks and sometimes six.

In 1981 there were 1,600 B.C. trollers working the entire coast from north of the Queen Charlottes to the southern Gulf Islands; 20 years later there would be 540.

And it seemed the entire fleet was here in Port Hardy now, jamming the wharves and floats, waiting out the weather and as restless as we were to get their season going.

We waited out the weather and the hours of diagnosis on the pilot by having our first official gear-tying lesson in the cabin. The drop-down Arborite table attached to the back wall turned the day bunk from dining room to workshop as boxes of shoe-sized silver flashers and coppery little spoons and a rainbow of rubbery squid-like hoochies piled up along with hooks, tiny clamp-stops, bright beads and spools of 50-pound-test Perlon fishing line. It was all I could do not to start making jewelry out of this gorgeous stuff.

We were tying gear to attract spring salmon and whatever sockeye showed up, because those were the only two of the five salmon species open to trollers this early. The Department of Fisheries and Oceans set the species openings in keeping with whatever calibrated voodoo equations they came up with to regulate an industry that was already careering into decline. But this year, coho season didn’t open until July 1, and pinks not until Aug. 1, so if we did hook one before then we had to shake it off (hence the barbless hooks).

A troller could still fish anywhere on the coast, inside or outside waters, for any species, then slap on a drum and go gillnetting in the fall. But by 1995, the DFO and its Round Table restrictions narrowed the window of opportunity to a porthole.

Trollers, who were hardest hit from every direction, were left stunned and angry and asking questions: Why was the most viable, sustainable fishery being systematically beaten down? Why were fish farms and sport-fishing camps taking over every good anchorage on the coast?

Battle lines were being drawn and every user group was ready to fight it out. But some had louder voices than others, and those voices were heard by more powerful ears.

Suddenly, a familiar voice called from the float. “Hey, Paul, Syl, you at home?” Boat etiquette insists on a call-out before stepping on the deck, a knock on the door, even if it’s open, and no entry until invited.

“Richard! Steve!” I bounded out the door and onto the float to give our friend and his deckhand a huge hug and cheek-kiss.

“Hey, good to see you,” Paul said smiling in the doorway. “We’re just about to go check on the pilot. Wanna get together for dinner tonight?”

“I’ll make spaghetti,” I chimed in. It was the only thing we could afford. With their bread and salad we would feast and laugh and tell stories and ignore the howling gale. And we’d ignore that the little bit of money we scrounged to get here was almost used up by fuel and repairs, and we still had to get to the B.C. Packers fish camp in Bull Harbour a few more hours north.

We would leave exploring Hardy’s handful of streets and infamous hotel bars for another trip. We needed to start fishing and making some money very, very soon, and if the weather calmed down the next day, we would head up to Bull Harbour and do just that.

That night in my bunk I felt like an arrow vibrating with energy and ready to spring from the bow.

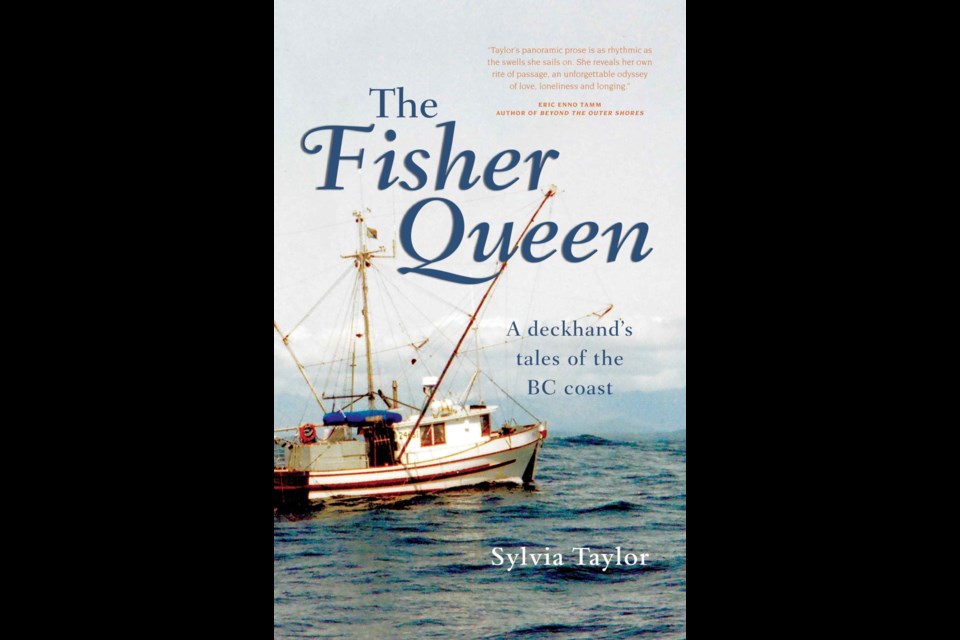

The Fisher Queen: A Deckhand’s Tales of the B.C. Coast

© 2012 Sylvia Taylor, Heritage House Publishing